H&D Bulletin #5

H&D Bulletin #5

Since 2021, I have been living off-grid on the waterways of London. Living this way has been a crash course in resource management, power consumption, and system design. It has also motivated me to research low-power computing, solar power, and permacomputing,1 a concept and practice inspired by the regenerative practices of permaculture. With the need to design a low impact system that would sustain my daily needs, these ideas began to coalesce around solar energy capture, battery storage and minor tech solutions. I started exploring my relationship with abundance vs. scarcity mentalities, and took a dive into the world of solarpunk.

How to practice solarpunk? One solar punk methodology has become a bit of a rabbit hole for me… At the end of 2022, I dissected a disposable vape. At the time I observed that vaporisers were littering the streets and parks in London. Cheap, colourful and sweet flavoured nicotine vapes were booming in sales. By 2023, 5 million vapes2 were being thrown away every week in the UK alone. It became apparent that these vapes couldn’t be disposed of safely. There were no recycling points. Councils and fire departments were reporting dangerous fires caused by single use vapes that were thrown into bins. As a result of a complete lack of regulation and communication, lots of these devices were simply thrown on the floor.

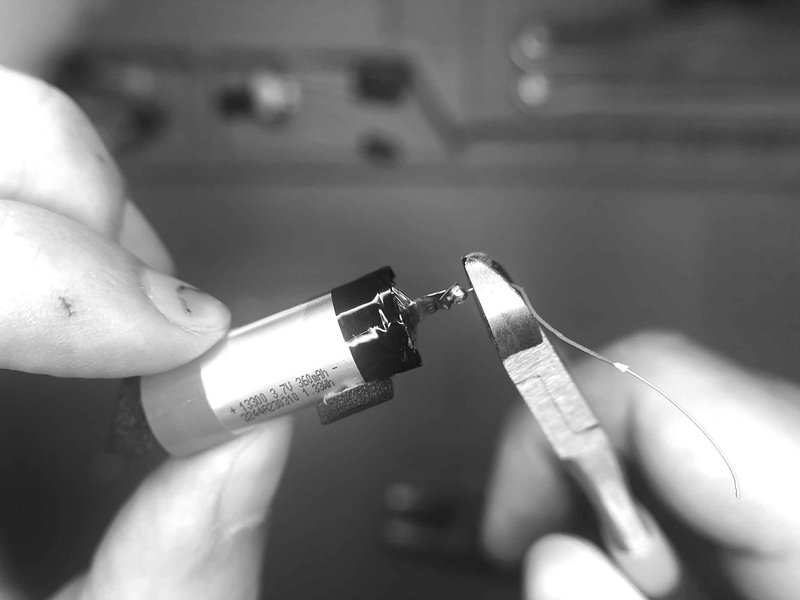

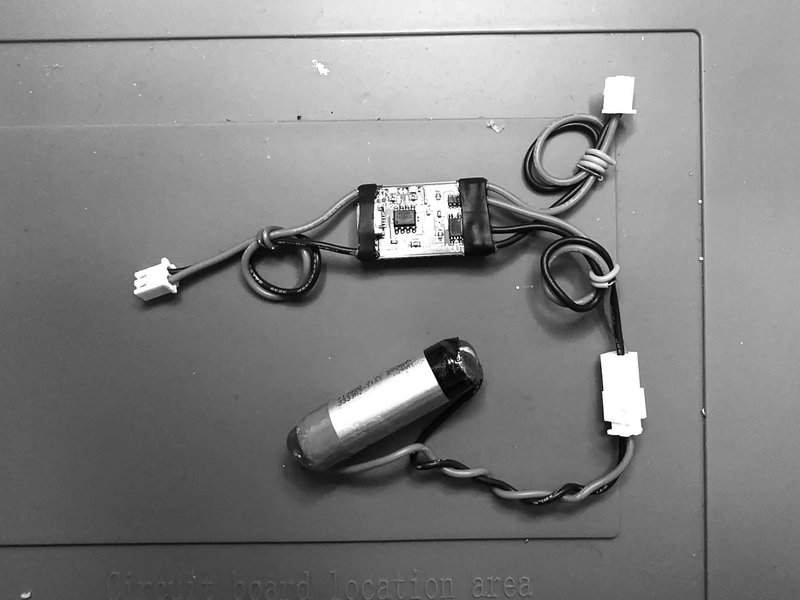

Pulling apart the device, I discovered and dismantled a simple electronic circuit, consisting of a lithium-ion battery, a pressure switch, and a heating element. I reconnected the battery to a simple circuit of LEDs and voilà! I had a light-emitting-diode moment (I had not seen a “real” lightbulb in years). What else could I use these batteries for? Could I recharge the cells? As it turns out, the lithium cells in these “single-use” vapes can in fact be safely recharged countless times. They simply don’t have the means to be recharged inside the devices because they are designed to be single use.

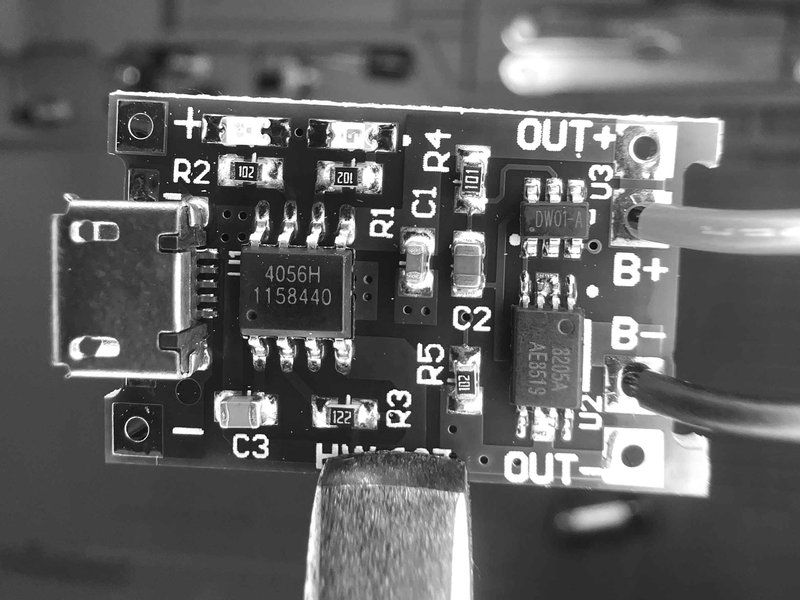

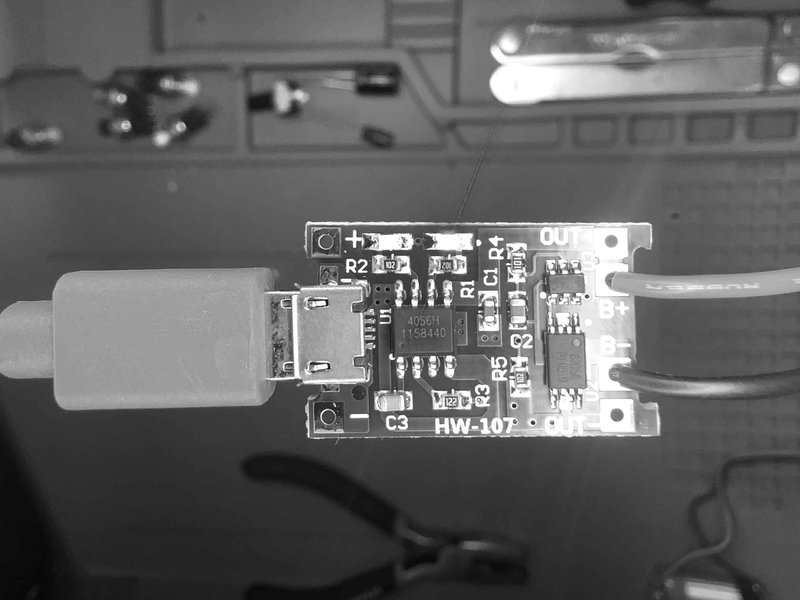

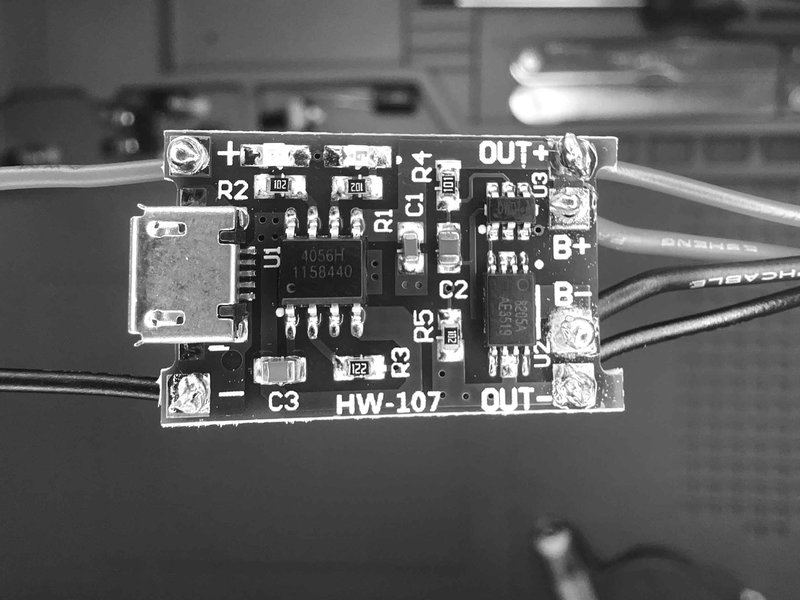

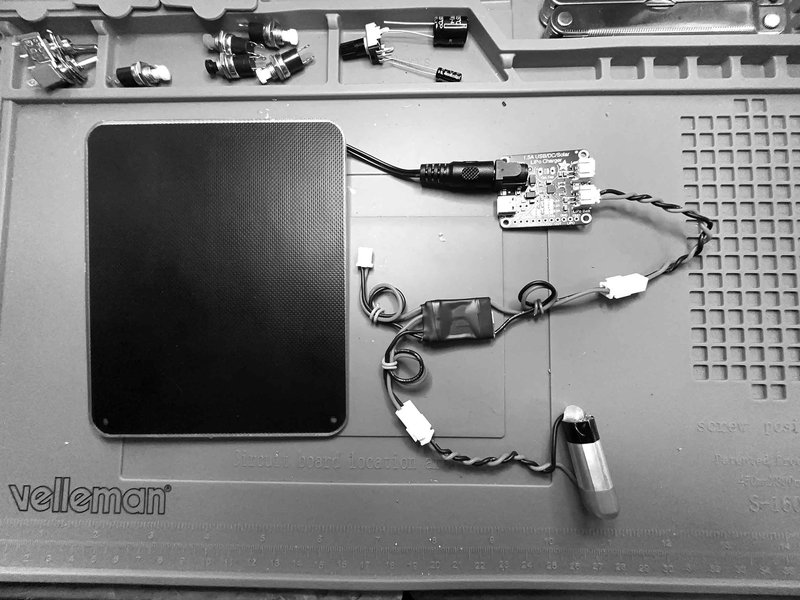

The devices have no battery management system (or BMS), which is required to safely recharge the cells. Online research3 led me to the TP4056 chip, a versatile charging module appropriate for charging 3.7 Volt cells – a standard for low power devices. The charging module has a micro-USB input, and additional wiring pads for auxiliary power input, which I later utilised to connect to a solar panel. It also has two outputs, one for the battery and one for a direct current load. The modules have LED indicators for voltage and charge status, which makes them ideal for DIY applications.

Soon, I had a fruity smelling box full of salvaged vapes to extract power cells from. I have found many uses for this renewed source of power, and now have a box of cells ready for breadboarding low power circuits. They are particularly useful for powering small microprocessor projects, and I have had lots of satisfaction powering small networked projects using ESP-32 and Raspberry Pi Picos. Great for DIY IoT projects, wireless controllers, and small lighting projects. When hooked up to charge from a solar panel via an MPPT, they become self-sufficient low power units. At H&D Summer Camp 2023, I facilitated a workshop in which we powered a network of ESP-32 and Pico microprocessors with the cells. Set up as controllers for a multi-player instrument, each connected to various sensors and switches. We then performed collaboratively with the networked instrument on the camp radio that evening.

Taking this concept further, I developed small circuits on perfboard integrating the cells, potentiometer, switches and a small OLED display, and retrofitted them into discarded portable television handsets. I then programmed a short interactive experience onto the devices, to be used as part of a collaborative improvised performance piece called Sunspeak.

I’m interested in repurposing the cells as a radical act of resistance. For me, these cells are the spark that inspires a sense of empowerment and agency against a system of extraction. A failing system that doesn’t meet the needs of consumers or the planet. Instead it is perpetuating systems of capitalism, colonialism, the exploitation of people, and exploitation of the planet.

It is demonstrably evidenced that the extraction of lithium has significant consequences for the environment and the communities who mine the mineral. Perhaps we should question whether so-called technological development equates to progress at all, especially when the means of production for new energy storage technology relies on extractive and economic colonial practices. The energy transition is unjust, and these cells are just a drop in the ocean in comparison to the tens of kilograms of lithium required for an Electric Vehicle battery, for example. Reusing them isn’t going to save the planet or the lives of those affected by resource extraction, nor those exploited in the process. I propose that the act of renewal can be an acknowledgement of where our day-to-day electronic devices come from. A recognition of our complicity in the system that demands and produces them. An opportunity to spark a conversation that considers the possibility of an alternative future.

Drawing from and exploring the ideas of permacomputing, this practice is a process of recycling, reconnecting, and renewing parts, resources, and energy. It’s about salvaging what we already have - in this case digital detritus - and giving it new life. To draw parallels with ecological frameworks, it could be considered a kind of digital ‘recommoning’ , which is about retaining and reclaiming agency in our environments, and being able to contribute practically in response to the failures we see around us. For me, it’s about having a toolkit to experiment, challenge the status quo, and rewrite the stories that no longer serve us.

You will need:

1) First, using a pair of pliers, pull out the mouthpiece of the vape. It’s a good idea to wipe this with some antibacterial fluid first, for hygiene sake - especially if it’s a found device.

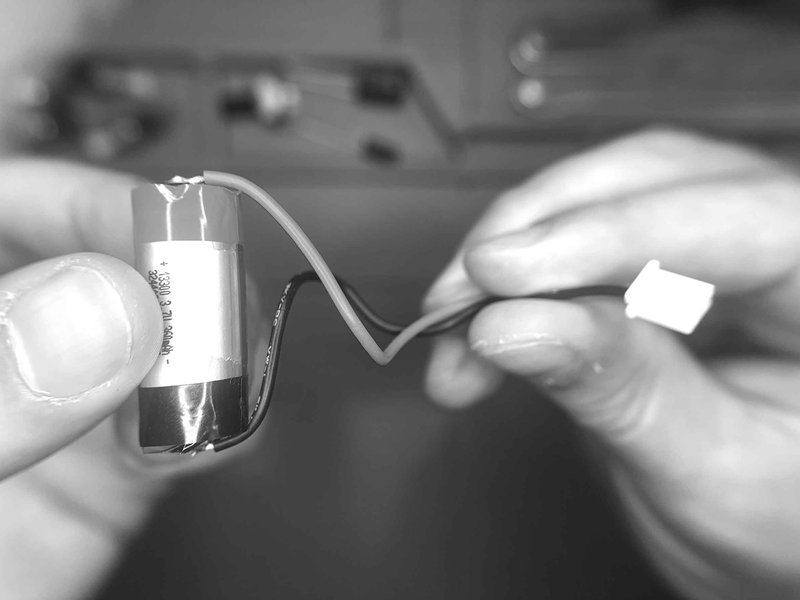

2) Carefully cut the wires between the battery and the rest of the circuit, being careful not to short circuit the battery cell. There will be three wires. Red for positive, black for negative, and a third colour (usually blue) which connects to the pressure switch.

3) If needed, desolder any remaining wires from pads on the battery cell terminals.

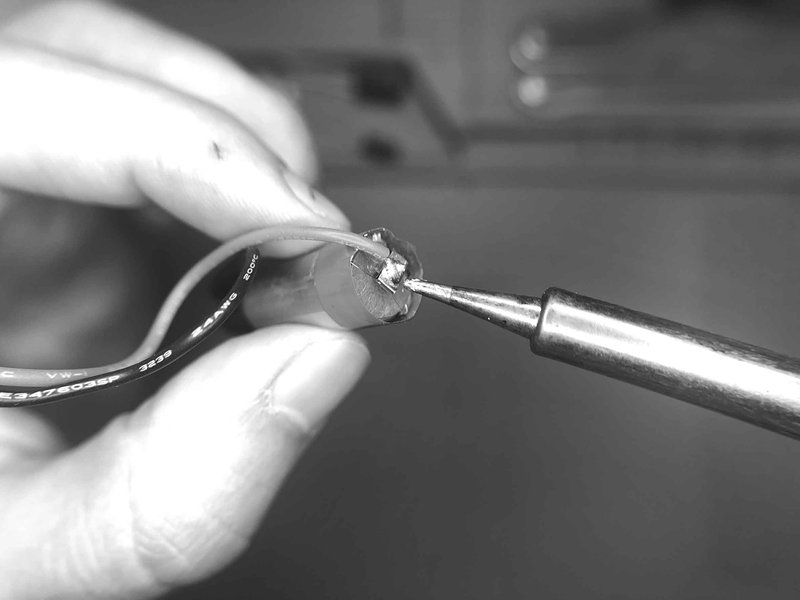

4) Solder new wires to the corresponding terminals of the cell. I have been using JST connectors to keep things organised and modular.

5) Using a hot glue gun, pop a blob of glue over the soldered battery connections to insulate and secure the terminals.

6) Solder the cables to the Batter (B+ and B-) outputs on the TP4056 module. Be sure to match the correct polarity.

7) You can now recharge the cell using a micro-USB cable!

8) To make full use of the charging module, solder a set of wires to the TP4056 input pads either side of the micro-USB port. You can also connect a set of wires to the OUT + and - in order to power a load directly through the module.

9) Using the JST connections, connect the charging module to an MPPT, and then to a small solar panel, in order to charge these via the sun.

In June of 2024 H&D and MELT (Ren Loren Britton & Iz Paehr) hosted a criptastic hack meeting – a hands-on workshop that brought together MELT’s imaginative and speculative design approach to dreaming up Anti-Ableist technologies with H&D’s hands-on hacking approach to imagining more regenerative and equitable techno-futures.

Inspired by a lineage of crip 1technoscience, the approach to the session was equally practical as imaginative-fictional, resisted tech-solutionism, and aimed to generate energies around multitude conceptions of time2

MELT and H&D worked together on this workshop over the course of several work sessions, getting to know each other in the making process, through engaging in each others research and practices, by spending time together in Berlin, Amsterdam and online, and by sharing and preparing readings for each other. With this contribution we would like to share the workshop script that we developed throughout this exchange, and hope by (re)publishing it will provide collective energies, imaginaries and practices around crip time, and perhaps new workshop iterations can evolve from it in the future.

We invite you to ride the unruly/unexpected/fantastic undercurrents of crip time3 with us and create other collective imaginaries for interfacing with crip time that counter the universalist assumption that all bodies and minds experience time and space similarly.4 Compulsory techno-capitalist paradigms of time-efficiency,5 consistent and seamless labor performance and presumed able-bodiedness pattern time structures that are inaccessible for many people.6, 7 Ren Britton writes: “My bodymind is expected to move quickly, to keep up with turbo-capitalist computational clock time that counts to the millisecond.”8

ID: Pernilla who is in the physical space is making a picture of the online participants

We propose hacking as a way to counter the notion of universal time and tune into crip time.9 Crip time shows that there are other ways of being in time: slow, in attunement with pain or symptoms,10 with JOMO (joy of missing out), in resistance towards capitalisms temporal demands.

ID: Workshop participants presenting their clocks / steering wheels in an enclosed workshop space. There is a screen on the right, where online participants are following. Others are standing around in the physical space following the presentation

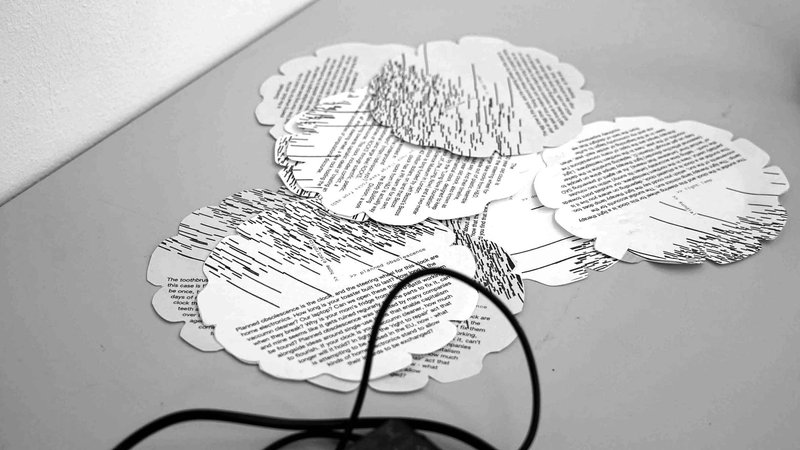

We invite you to imagine and protoyped clocks that work against gregorian clock time – clocks that are sensitive to interfacing with crip time. We are also worked with the concept of the ‘steering wheel.’ Such steering wheels let us navigate and attune to different individual and collective temporalities. They help us approach the body as something that is constantly changing, that may go through and stay in states of illness, exhaustion and disability. Steering wheels are something you need in order to interact with/make sense of otherwise timelines.

ID: A pile of worksheets. The worksheet contains the descriptions of the steering wheel components and are cut out in the shape of an imperfect circle.

We invite everyone to engage in a small ritual with us for giving up temporal dependencies. As a start, we ask you to decide upon one timely device that you would usually depend on and that is attached to Gregorian time. This could be your smartphone, smartwatch, regular watch, your morning alarm, a calendar reminder, your social media push notification. You can choose something that you are okay with giving up for the duration of the workshop, however large or small.

The steps are:

1) Place your Greogorian clock/object/entity in front of you.

2) Promise your object that you will pick it up again in the future.

3) Put it into your backpack or somewhere else where you won’t be in touch with it for the next hours. This could also just mean: Closing your email program, or stopping your alarms.

Thank you – We are now ready to dive into the ocean of crip time.

[ Here we take some time to contextualize the notion of crip time and what it means to us. If crip time is a new concept for you, we invite the reader and fellow workshoppers to visit the proposed references in the bibliography to familarize yourselves with crip time. Iz shares that “Crip time exists because many people have expectations about time: How long should something take? What is a normal amount of time? Many disabled people say: Crip time is normal for us. In this workshop we say: For crip time we need new clocks.” ]

On a ship on the ocean, steering wheels are used to find a new direction. The steering wheel is how the clock is in operation for the context of this workshop. Some clocks are steering wheels at the same time, others are distinct. Think of your clock and its steering wheel as the what and the how. The clock is the ‘what’ and the steering wheel is the ‘how’. These steering wheels modulate normative time through being slow, by engaging shifting materials, by inventing other temporal patterns, or by incorporating noise/rhythm. They are invitations/portals/ wormholes/custom controllers to interface with the crip time ocean. We invite you to build these otherwise clocks from materials we have brought.

While we do this, let us be mindful of some parts of the oceans where sharks swim – these places we ask you not to visit: For example, please don’t use your steering device / clock to interface with a disability experience that you do not personally have to prevent nondisabled assumptions. We ask you to start from your own experience and how you would interface with the crip time ocean.

We have prepared different materials for you that represent ‘clocks’ (what) and ‘steering wheels’ (how). Those are the components that you can use to start working on your clock, in smaller groups of individually if you prefer.

The hourglass is the clock, and the steering wheel for this clock is a bucket of sand. As a bucket of sand, broken down from the hardest mountains, crumbling into boulders, slabs, hefty rocks, smaller rocks, pebbles, granules and eventually - sand. The transformations of sand from mountains, hammering away at the disintegration of matter from the literally massive into the particulate. Hourglasses and the sand they hold pose a specific kind of material time, its both the amount of time of the sand moving between one bulbous shape to another, and the holding of what could be seen as mountains, worn down by time, in a small glass bulb.

Downloads is the clock, and the steering wheel for this clock is the load time. How long does each download take? Do you need multiple plugins to make that download work? How about updates to the software? How many programs have you had to download to make that one other program work and how long did it take? And how about your trash bin? What about all those installers you had to install… Do you still need them now that the program is downloaded? How long did it take? And could you find that link again if you needed to?

The crystal oscillator is the clock and the steering wheel are crystals. Crystal oscillators are part of many digital circuits because of its ability to generate a stable pulse and therefore creating a clock signal. With a reputation of being high-precision, this slab-cut power stone is connected to its environment and able to adapt thereafter. Temperature, power supply and other components (neighbors) affects the quart’s rhythm. What changes your rhythm, and how does that affect your dance, your talk, your songs? What/who resonates with your pulse and what set’s its frequency?

The toothbrush is a steering wheel of time that comes regularly. The clock in this case is the same as the instrument. Depending on your habits it might be once, twice, thrice a day - or every other day. Sometimes, after a few days of not engaging the toothbrush, your teeth may feel grimy, as a clock the toothbrush freshens you up, gets into the nooks between teeth and itself needs to be replaced regularly. Toothbrushes, over time, lose their usefulness for teeth and may become agents of cleaning - all of the edges of tiles and corners may be easily cleaned by using a toothbrush and in this way its function changes over time.

The sundial is the clock and this steering wheel for this clock is a light therapy lamp. The light therapy lamp mimics the sun. The sundial accounts for the movements of the sun, which you could say the light therapy lamp does too. The sundial as a clock is a situated clock, depending on where you live it is partially useful. Here in the northern hemisphere, our sundials point towards the north - telling time accurately (when its sunny) within two minutes of ‘actual time’ (whatever that means). As an agent of preventing SAD (seasonal affective disorder) light therapy lamps shine on people to help us get enough Vitamin D, replacing sunshine in the darker months of the year, here in the northern hemisphere.

Push notifications is the clock, and the steering wheel for this clock are screenshots/screen time. Just think of all of the notifications of space/place/time/reminders that pop up on your phone. And the reminders of your material connection to screens through the screenshots we take of where we need to be, and how. When and why. And the screen time notifications that tell us how many hours we have labored in front of this screen, daily, weekly and monthly.

The 10,000 year old clock is the clock, and the steering wheel for this clock are the large fake rocks from H&D. These large fake rocks, made out of plastic resemble rocks, cosplay rocks you could say. And their timeline may in fact be similar. The 10,000 year old clock, also known as ‘the clock of the long now’ is a mechanical clock, designed to keep time for 10,000 years. Its being built by the “Long Now Foundation”11 and a two-meter prototype is now on display at the Science Museum in London. The first full-scale prototype of this clock is bing funded by Jeff Bezos’s Bezos Expeditions project, with a budget of 42 million dollars, on land that Bezos owns in Texas. Even though this clock has its own PR team, the history of the large fake rocks from H&D is actually way more interesting. These rocks existed in the Body Building exhibition at TETEM from The Underground Division, a work of theirs titled “Rock Repro”12 - a collection of computational (and large fake) ROCKS, telling unstable stories of ROCKS through scientific, poetic, public and technological discourse. This clock, includes conflict, a 10,000 year old clock moving towards capitalist ideals of ‘creating an iconic clock for all’ and a steering wheel, a fake rock holding the difficulties and possibilities of computational discourse.

The egg timer is the clock, and the steering wheel for this clock is also an egg timer. Timing around three minutes in gregorian time, this span of time indexes just about how long it takes for an egg’s innards to transform from liquid to soft-medium-or-hard-boiled, depending on how high the altitude is at which you cook. This timer clicks down, and rings like a school bell, loud - and finished - at the end.

Planned obsolescence is the clock, and the steering wheel for this clock are home electronics. How long is your toaster built to last? How long is the vacuum cleaner? Our laptops? Can we open these things up and fix them when they break? Why is your mom’s fridge from the 70’s still working, and mine seems like it gets ruined regularly and the parts to fix it, can’t be found? Planned obsolescence was invented by many companies alongside ideas around single-use items that enable capitalism to flourish. If your clock is your vacuum cleaner, how much longer will it hold? In light of the ‘right to repair’ act that has been proposed to the European Parliament and Council, now - what kinds of home electronics stand to allow their innards to be exchanged?

The watch is the clock, and the steering wheel for this clock is Watchy. Watchy is an e-ink watch with open source hardware and software, a PCB makes up the watch body - and it can be customized with 3D printed cases and watch straps.13 You can upload your own watch face, images and websites to it - and it can sense movement - up, down, sideways, otherways. Watchy can be reprogrammed, and interacted with using the Arduino IDE. Watchy can sense the swinging of our arms when its attached to our wrists or ankles and we can watch our limbs move on a small website that tracks its movement. These movements approximate and yet don’t compile a proper ‘clock’ - after all, what is a clock?

Technical documentation: https://github.com/hackersanddesigners /criptime

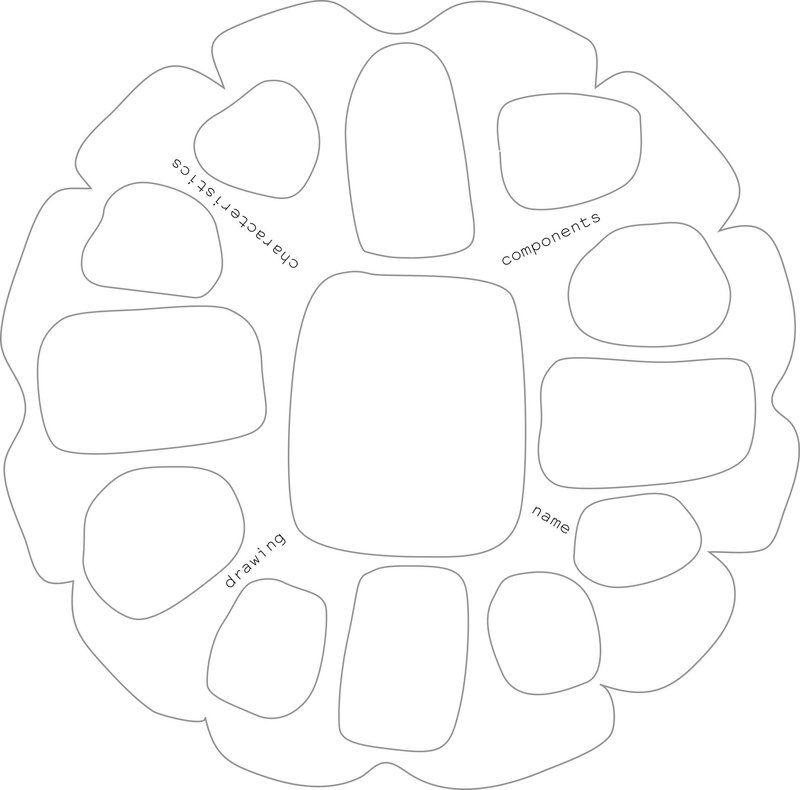

ID: A worksheet with input fields for the name, characteristics, components of the clock and one to add a drawing of it. The shape of the worksheet is round with imperfect edges

In this written conversation, André Fincato and Karl Moubarak discuss the process of working on the latest version of the Hackers & Designers website. It is about the pains and joys of decision making, the complexity of creating a website for a growing group that includes many voices, while paying attention to and taking important steps in improving the site in terms of accessibility, a more sustainable server infrastructure as well as multilingualism for the content and structure.

KM = Karl Moubarak

AF = André Fincato

KM: What was the initial trigger to work on an update of the already working Hackers & Designers website? What was wrong with the old one?

AF: The previous version of the website had some recurrent small problems, which were learned and handled by the few people who frequently updated the wiki. My motivation behind reworking the site and being able to archive the wiki was initially triggered when I accidentally wiped out the entire server the year before. So I wanted to create a live archive of the wiki and an easy backup format. In this case this meant creating HTML files + images etc. At the same time, I must admit, I got caught by the bug of static websites and ‘smol web’ by browsing certain areas of the Fediverse,1 and somehow by building a live static site generator everything came together. Luckily the smol web bug disappeared quite soon, after 6 months, because I realised I could have this more interesting (and sophisticated) live-updating system to generate an ongoing archive of the wiki thanks to the MediaWiki APIs.

KM: What is the “smol internet” bug? Why is/was it relevant for our website?

AF: The smol web (see smolweb.org) is part of an ongoing obsession / preference / moral imperative to go back to writing software simple enough so that one human being can understand it all and to avoid ‘bloated software.’2 The outcome is often that people use computers only through the command line interface to minimize their computer’s processing power to the most essential and show us that the only way to use a computer is by typing text in it. Everything else beyond such text input is considered bloated. You are suppose to “man up,” get behind the terminal and throw out your mouse.”3 The smol web is a branch of this fediverse phenomenon that contrasts big internet corporations that primarily build social media apps, big websites, algorithmically enhanced. The smol web proposes to go back to a simpler web. Sometimes web 1.0 is the primal reference, sometimes people suggest that you should learn how to build your hand-coded website and turn it into a craft (https://html.energy/index.html). It all smells very reactionary even though the starting point can be a set of problems I agree with: see for instance the case with the permacomputing scene (http://viznut.fi/texts-en/permacomputing.html and https://permacomputing.net). They argue for computer frugality, low-energy software, commonality, and the like. Somehow I haven’t seen a mention on the permacomputing wiki that permaculture — a concept from the 1970s they borrow from — has been heavily criticized already at the time, for being sold as a form of advanced new technology in white western culture, whereas it has been the core principle of how to engage with land from indigenous populations around the world since a longer time; is permacomputing a continuation of these politics? In computer culture people tend to go back to the golden days of Unix and the C programming language.

KM: A remark that came back often about our old website is how slow, inaccessible and clunky it was. Even if for a fleeting moment, do you think your dive into the “smol internet” trend / moral imperative when approaching the development of the new site helped resolve some of these issues?

AF: I think what helped was not the smol web, but rather the desire to make an archive. Originally, it was the plan for the new website to be a live archive backed up in git repositories, which should live in different locations. The HTML-first approach drove it. The trend of a few years ago about static site generators was more influential to the final outcome of the new website. The smol web is more a “moral + cultural” layer.

KM: My last question about this phenomenon: Would you describe our new website as “smol”?

AF: On a technical level, we cannot describe the new website as part of the smol web, because the way we run it is quite unorthodox and not small at all: we run a MediaWiki instance and create a new HTML page whenever an article in the wiki changes. A smol web approach would probably erase the MediaWiki variable from the equation. We also do it all in Python as a running program (not a one-off command as opposed to how a static site generator would work), which is slow and not very efficient. Besides this, I think the smol web is all about being part of a certain club of people following a certain set of morals, camouflaged with a layer of technical reasons, and I personally don’t belong to it. It’s possible though that some part of H&D will find the phenomenon interesting in the future and or are engaging with it already, for which I cannot speak about.

AF: what do you think of the smol web if you have any impression of it?

KM: I have to admit, maybe with a little bit of shame, that I fully bought into it at first. I was very excited by the growing culture of hand-making websites (again) and the metaphors of websites as gardens that need to be maintained and kept with a “personal” touch and a lot of care. This was an ideology that I really wanted to see reflected in our new website. Fortunately the reality of website-making these days is very different than a hand-crafted, well-kept and beautifully manicured garden. Our website was an example of a wild, weedy mess with many hands fervently trying to fix it up as it was being made, sometimes under precarious conditions. There are many moving parts, a lot of holes, leaks, and hectic efforts to continuously mend them. The garden metaphor just doesn’t hold up. This is a good thing.

AF: For me it ultimately comes down to a new moral standard that asks to be followed, which does nothing against the climate crisis. After all, there’s a lot of well-written, efficient, websites that are also part of complex software , so it’s more of a spectrum IMO than creating another division of who is in the club and who is not because “bad”. xD

KM: If not “smol”, what were the core ideologies you wanted to take into account when building this website?

AF: I can’t list out the ideologies right away, so I’ll write down the core points I had in mind at the beginning:

So, maybe the core ideologies were:

Things have changed in the process, also quite drastically!

KM: It’s eye-opening to see how these were leading principles for the project, and these are definitely visible in the website’s inner workings as it currently stands. Indeed the reality turned out a little different. What conditions took the project further away from these principles?

AF: The website has become more reliant on the MediaWiki for many things. Maybe for the better, but I really at first wanted to move away from it. Maybe you can talk about it, since these were the changes you introduced to the project, which helped us to actually finish it? (:

KM: What I remember from the discussions with the group is that the proposal to give up MediaWiki was left unanswered. I am not sure what the reason was, but I imagine it had to do with us not having proposed a “better” alternative. In a way, despite it’s clunky interface, backwards API and messy developer experience, MediaWiki is a good and reliable space to write, collaborate and edit articles for the group. Although not a Content Management System, MediaWiki has been the best system for us to manage our content…

AF: That’s true. I won’t touch on that subject in relation to group politics, and overall as I said at the beginning, the idea of dropping MW stopped being an option for me too once I decided to leave the group. I think your suggestions nonetheless were less about strictly wanting to stop using MW, and more concerned, in a practical way, about how to implement certain features without using MW. In retrospect, if you did not suggest those middle-ground decisions, I would have probably found myself stuck in there because of “ideology.”

KM: Glad my amateur brain could be of help.

AF: Given the conditions just outlined, what was your experience in joining an existing project running since a few years already?

KM: My incentive to join the project was to work on two main aspects: the accessibility of the website and it’s maintainability in the long run. To be completely honest, I was scared of being handed over the responsibility of maintaining a repository like the last one. I am not the most experienced Python programmer and the way the former repository was written really followed one individual’s way of thinking. So for this project, I really tried to be involved from the start, even if a bit uncomfortable, and to follow along, process and tried to contribute where I could.

I’ve also had a positive experience of our exchanges. I felt I could get comfortable working on the parts of the project I was confident about such as writing more accessible HTML and CSS, and whenever I wanted to get a little bit uncomfortable and learn a bit more of the pythonic inner-workings of the site, you left me enough space to jump in and write together :)

AF: As a side comment, the previous website was where I wrote my first ever lines of Python code and my first exposure to web REST APIs. I did not know how to import Python functions (or that you could!) so it’s just one big file.

AF: What were the hardest things to understand in the process of joining the project?

KM: My initial response to this is technical: the repository of functions and classes was a lot bigger than I expected, and I wasn’t yet used to working on such large project with many imports. With some documentation and many many explanatory meetings, this eventually turned out okay.

Zooming out, the biggest difficulty I had with this project was it’s fluid timeline. We started in 2021 by gathering feedback from different sources, getting our current site audited for accessibility, consulting with experts and listing out the needs of the group. For many very justifiable reasons, we weren’t able to stay on track with the initial timeline we set for ourselves. We pushed and pushed until we finally deployed the website in February of 2024. A lot changes in people, an organisation and on the Internet in three years. It often felt like a construction site for a building with changing architectural plans.

Another challenge was being part of the group whose website we were making. There is a joy in working on our “own” project, but it was complicated to account for the needs of everyone in the group while being one of these people. In a way, I missed the distance and pressure of having an external “client” (for lack of a better word). I really wanted to be selfish with what we make but couldn’t as it had to work for everyone.

KM: How was it for you to juggle your own needs and those of the group when working on this project?

AF: I more or less did what I wanted, adjusting along the way for things that seemed to be helping the project (in those areas at risk of getting stuck forever). I perceived very little communication and exchange with the rest of the group, except at the end when it was time to dress up the website at which point it was already three years in and the visual design was not my focus, so I went along with it.

AF: How do you see maintaining the project after you “inherited” it?

KM: I am happy to “inherit” code that I was involved in writing and can understand. So far, it’s been a joy to go into and follow the documentation, and make changes where necessary. It’s clear that this repository was written to be maintained in the long run. It’s still a bit of a challenge every now and then to “enter” the development mode of the project, as I have to start up at least three different services to make any change, but maybe that’s something to work on in a v3.

One thing I think about sometimes is how central my position in the maintenance of this website became after your departure from the group. I am afraid of being a point of dependency (and potential failure) for any project as essential to the group as this. Like many of the infrastructure related tasks in our group, my intention for future maintenance is to collectivize this task: I would like the responsibility to be shared between multiple different people in the group. Let’s see what they think about it ;].

The Fediverse is a decentralized social network where different websites talk to each other using a specific protocol (ActivityPub). A website in this case, is an ActivityPub instance (eg. a web server) where users can sign up for an account. Each instance can decide to which other instance they want to talk to. This is all in direct contrast with commercial social media platforms, where a company dictates unilaterally how the given network operates. For more on the topic, see Seven Theses On The Fediverse and The Becoming Of FLOSS.

Bloated software is a term used with a negative connotation by a computer user towards a certain software having lots of unnecessary functionalities that makes it slow or power hungry. Often times, the term is used with a big emotional charge attached to it, as it comes from the experience of a frustrated and / or unhappy computer user. Sometimes the term goes through certain phases where it’s used a lot in a manic depressive way expressive more a sense of fear and obsession of the user rather than a software being actually bloated in any actual way.

See Terminal boredom, or how to go on with life when less is indeed less.

Contributors: André Fincato & Karl Moubarak, MELT (Ren Loren Britton & Iz Paehr), Anja Groten, Heerko van der Kooij, Karl Moubarak, Pernilla Philips, Michael Fowler, Nous Sommes Partout, Thomas Rosser

Editors: Loes Bogers, Anja Groten, slvi.e

Design: H&D (Anja Groten, Juliette Lizotte, slvi.e)

Typefaces: Degheest:ghost: Fonts is part of the project “Reviving Ange Degheest” by Ange Degheest, Eugénie Bidaut, Oriane Charvieux, Mandy Elbé, Luna Delabre, Camille Depalle, Justine Herbel, May Jolivet and Benjamin Gomez, a sort of resurrection of the memory of Ange Degheest and other forgotten women in the field of type design before the 1980s, bearing witness to the technical upheavals in printing and telecommunications in the second half of the 20th century.

Printing: Terry Bleu, Amsterdam

COLLECTIVE CONDITIONS FOR RE-USE (CC4r)

Hackers & Designers, 2024. Copyleft with a difference: This is a collective work, you are invited to copy, distribute, and modify it under the terms of the CC4r gitlab.constantvzw.org/unbound/cc4r.

REMINDER TO CURRENT AND FUTURE AUTHORS:

The authored work released under the CC4r was never yours to begin with. The CC4r considers authorship to be part of a collective cultural effort and rejects authorship as ownership derived from individual genius. This means to recognize that it is situated in social and historical conditions and that there may be reasons to refrain from release and re-use.

Copyleft Attitude with a difference, 24 November 2022.

The CC4r was developed for the Constant work session Unbound libraries (spring 2020) and followed from discussions during and contributions to the study day Authors of the future (Fall 2019). It is based on the Free Art License http://artlibre.org/licence/lal/en/ and inspired by other licensing projects such as The (Cooperative) Non-Violent Public License https://thufie.lain.haus/NPL.html and the Decolonial Media license https://freeculture.org/About/license .