Front Image Spread 1

Front Image Spread 2

Introduction

How Material Comes to Matter

Workshops as sites of collective resistance and reimagination

Anja Groten, Márk Redele

This publication evolved from a shared urgency among students, educators, and researchers to foreground the pivotal role of workshops and labs in art and design education, and to recognize them as critical and versatile spaces for collaborative learning and material-driven inquiry.

Although there is a common agreement among students and educators that “thinking” and “making” are intertwined processes, there is a deep-rooted division that persists within academic frameworks. This publication aims to discuss the hierarchies and exclusionary practices that frequently arise within academia, such as the disconnect between classroom learning and material experimentation in workshops. Drawing from diverse perspectives, the contributors aspire to cultivate alternative, collective, and reciprocal approaches to learning with and through materiality.

How Material Comes to Matter begins with the acknowledgement that the planet we inhabit has been damaged through processes that implicate us all. In the face of the unfolding climate catastrophe and increasing social inequalities, it has become impossible to ignore the entanglement of humans with the material world, the ecosystems we inhabit and disrupt. What we call “material-based research” emerges from this recognition; it’s a way of attending to matter not as inert resources, but as active participants in shaping how we live, design, and imagine futures. Material-based research asks how materials themselves—entangled with histories of extraction, survival, and resistance—can become agents in shaping new knowledges and futures.

Turning towards materiality is an attempt to make sense of and negotiate the catastrophic times1 we live in—a time in which material realities could not diverge more extremely, and wealth and power could not be distributed more unevenly. Materials are being re-examined in sociology, philosophy, and cultural theory. Philosophy strands such as new materialism, actor-network-theory, and posthumanism orient us towards things, matter, and ecosystems, and urge us to take seriously the entanglement of human and nonhuman actors.

In her presentation at the lecture night in December 2024, researcher and designer Julia Ihls proposed that matter possesses its own agency, an autonomous existence with contradictions and conditions. (pp) This perspective is particularly relevant in the field of bio-design, where the integration of living materials and organisms into design challenges conventional notions of materiality and ethics.

The call to acknowledge nonhuman participation in the collective of human-organism-animal-thing-machine has enabled arts and sciences to reformulate cultural imaginations of how we relate to and affect our environment, helping to amplify concerns about human involvement in the unfolding climate injustices that envelop our time. While these perspectives broaden our imaginations, they also risk abstraction and detachment, skipping over urgent social justice demands by those already living with the consequences of extractivism and ecological collapse.

Tracing the dark and storied past of phosphorus, artist Clem Edwards reveals the deeply entangled lineage of the element, from the alchemist’s basement to colonial industry, and imperial warfare to modern geopolitical violence. (pp)

Clem’s careful disentanglement of phosphorus’ implicancies2 reminds us of the necessity to stay alert about claims that center more-than-human perspectives to create new climate imaginaries. That is, many such attempts risk jumping over and deprioritizing unresolved “social issue demands by racialized groups for the ‘greater good’ of an ecosystem.”3

Against this backdrop, we invite our collaborators and readers to pay greater attention to material-based research, the “simultaneous thinking and sensing of various moments of material existence,”4 and how they matter.

As artists, designers, and researchers, the conviction to take seriously knowledge produced and shared through the senses leads us to revisit the format of the workshop. Two meanings surface when we trace its genealogy: the workshop as a physical site of artisanal and artistic production, and the more ephemeral meaning of the workshop as a format for assembling groups of people to produce and achieve something together in a short amount of time.5 Far from neutral spaces, workshops are sites of contestation where hierarchies of knowledge, expectations of productivity, and neoliberal ideals of innovation are negotiated.

This publication brings together both meanings of “workshop,” and is interested in the different methods of learning and productivity they have inherited. Workshops—or, in some contexts Labs—bring about particular ways of coexisting in a space, along with social codes, and forms of interaction, such as the skill of negotiating the expectations of those who enter the workshop without much experience. Expectations of how much time certain processes take are recalibrated when they do not align with the wider ethos, pace, and culture of the space. Students at art and design schools learn to attune to these conditions, to the rhythm and prevailing social-material conduct of a workshop.

The conversation with bio-designer and researcher Sam Edens opens up protocols of communal care and safety when working with living organisms. It proposes collective vocalization exercises that make the often implicit handling of equipment and materials explicit and tangible to others. (pp)These practices are not only safety measures, they also give voice to the materials and the processes they undergo, cultivate students’ sense of agency, and foster sustained critical attention toward the actions they undertake.

Workshop specialist Mathild de Clerc further reflects on such socio-material protocols—specifically, on how the ways we do and make, as well as the decision about which materials and equipment get to enter these spaces, have a significant impact on how we relate to each other as people—as fellow students, colleagues, and friends, and on the ways we work and exist together. (pp)

The workshops at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, specifically, carry peculiar social-material conducts, temporalities, and practices of coexistence: slowness, care, cooperation, openness to the unexpected.

In Catastrophic Times by Isabelle Stengers reminds us where economic growth and the innovation economies have led us, urges us to slow down, and make ourselves pay attention. Her proposition—the Art of Paying Attention, which is not simply the capacity to pay attention but a matter of learning and “cultivating–making,” ourselves to pay attention—is an assignation to concretely reinvent modes of production.

“Making in the sense that attention here is not related to that which is defined as a priori worthy of attention, but as something that creates an obligation to imagine, to check, to envisage, consequences that bring into play connections between what we are in the habit of keeping separate.”6

While critical attention must be paid to the use and distribution of material on a larger global scale (i.e. tracing carbon footprints, toxic materials, and waste production), it is equally important to consider the socio-material intricacies that are close to us. It is as if the clock ticks slower in the workshops. Workshops are not only places of manufacture, but also laboratories for learning how to attune to an environment, its rhythm and social conditions, and how to act collectively. Such sites of making bring about particular (not universal) collective conditions—social-material conducts and forms of interaction that derive from the necessity of taking care of a space, maintaining material repositories, tools, and infrastructure.

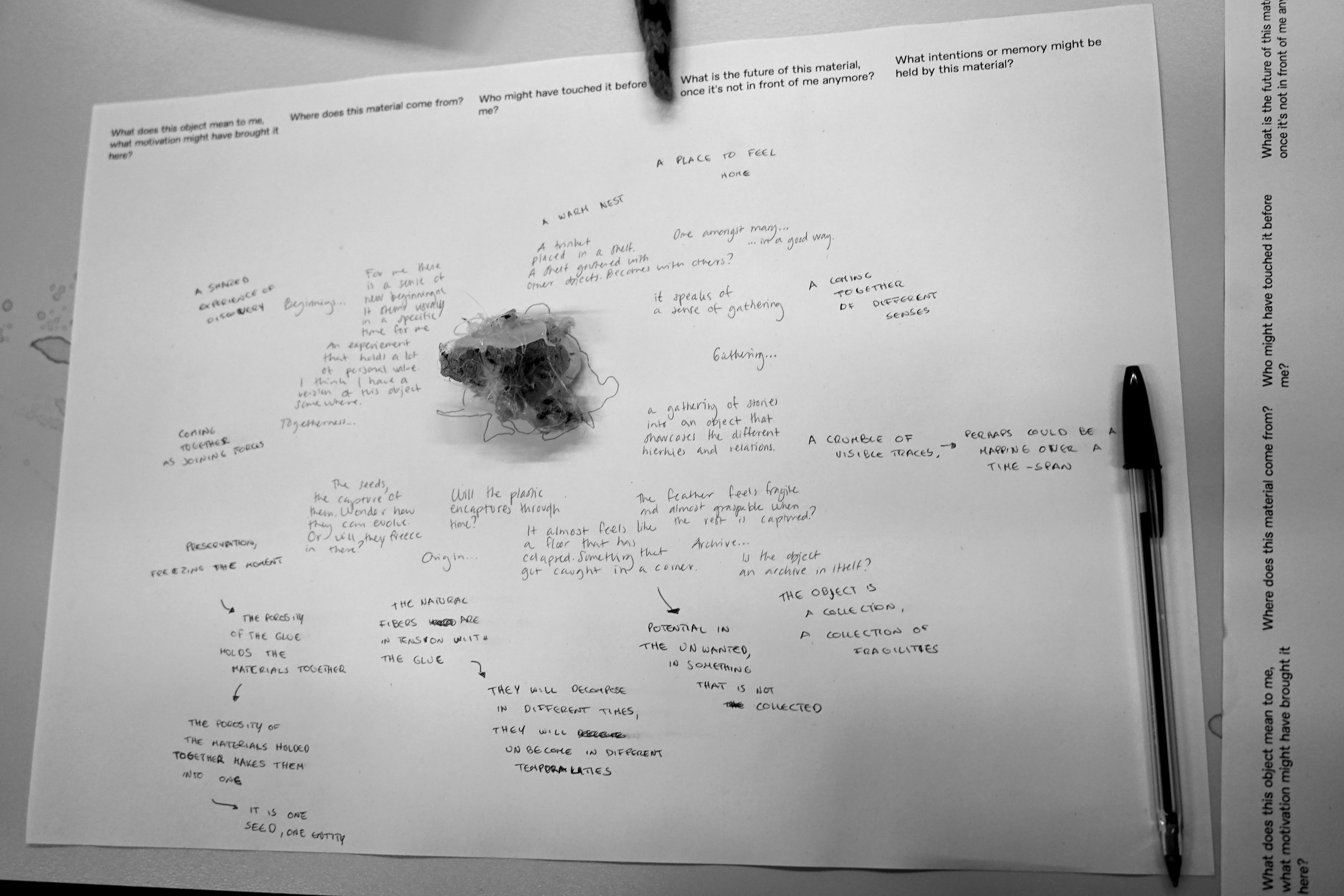

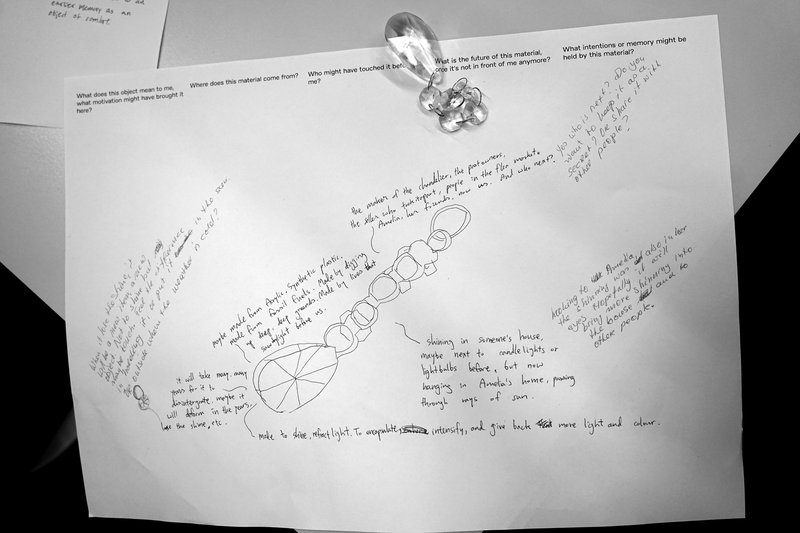

How Material Comes to Matter departs from the assumption that materials are not inert matter but agents entangled with histories, politics, and futures. Following Sara Ahmed’s call to consider the “grounded nature of use,”7 we consider materials as carriers of histories of extraction, transplantation, and resistance. Karen Barad reminds us that “practices of knowing are specific material engagements that participate in (re) configuring the world.”8 In this light, workshops become spaces where materials can narrate their own utility, revealing new possibilities for knowledge and meaning. Knowledge-making is always world-making.

Marjolijn Bol, a historian of craft, heritage, knowledge, and the environment prompts us to look to the past and learn from the ways institutional practices of collection, preservation, and repair in Western Europe have shaped what is considered valuable. She also raises questions about traditional notions of permanence and the initial impulse behind creating lasting objects. (pp)

To reimagine material engagement, we evoke decolonial thought, particularly Sylvia Wynter’s vision of cultural production as a dynamic of resistance. From Caribbean histories of rebellion and survival, we inherit models of “reparative rebellious inventions”9 that resist extractive economies and propose other ways of living with matter. In this light, with How Material Comes to Matter, we ask if spaces of art- and design-making and material inquiry can serve as marginal yet generative spaces where humans and materials co-produce responses to crisis. Can workshops become sites of resistance and reparation?

Within art and design education, especially at GRA/SI (Gerrit Rietveld Academie and Sandberg Instituut), workshops (werkplaatsen or Werkstätte) play a crucial role in accommodating the student’s development, both in their attempts to materialize critical thought and their development as future critical makers. Engaging with the infrastructures of material-based research and education, one needs to inquire about other, collective and boundary-crossing ways of designing education.

How Materials Comes to Matter has served as an excuse to reach out beyond our usual go-to places and connect people, workshops, departments, and institutions that are usually not accessible to us.

Through initiating various activities and collaboration we tried to sensibly “agitate” the habits and norms established within the specific material cultures, i.e. of the workshops, by initiating collaborative formats with carefully chosen partners in and outside of the institution. The aim was to foreground and uplift the researchability of material-based practices and develop formats in which such practices can be questioned in mutually generative ways.

The conversation with IPOP (In Pursuit of Otherwise Possibilities) reflects on the process of co-developing a workshop with BB (Bookbinding Workshop at Gerrit Rietveld Academie), in which diverse understandings and practices of embodiment were explored together with the students in the Design Department at Sandberg Instituut. The shared goal centered on learning to make and use glue from scratch, not only as a material but also as a way to investigate its performative potential. Beyond its function as a product, glue has a metaphorical stickiness, and the abundance of shared teaching and learning that unfolded through this process highlighted the rarity of such moments within an efficiency-driven educational system, prompting questions about scarcity, time, and resources. Perhaps the most significant outcome of this collaboration was the value of sharing space as facilitators, witnessing each other’s methods, and learning through one another’s approaches to facilitation. As educators, such opportunities to observe and be enriched by each other’s practices are rare, and this exchange highlighted their profound importance. (pp)

The collaboration also increased awareness of the necessity to critically challenge common tropes that have evolved in and around the workshops as sites for material production—such as “mastery” (of a tool or technique), “novelty” (of an idea or outcome), as well as “tacit knowledge” (a form of embodied knowledge that allegedly cannot be shared)—and to reconsider them as places of collective material practice, where social and material engagement are closely intermingled.

The streams of research threaded together in this book aim to provoke our collective socio-material imaginations by considering workshops as places of fruitful contestation. We see their potential to resist progress-oriented neoliberal trends and the economization of education, as well as the “maker-space mentality,” which reduces the act of making to efficiency- and output-driven activities. Instead, the trajectory foregrounded how workshops function as socio-material environments of care, where knowledge emerges through shared practice, maintenance, and situated engagement.

- Isabelle Stengers, In Catastrophic Times. Resisting the Coming Barbarism, trans. Andrew Goffey (Lüneburg: Open Humanities Press, 2015).

- "4 Waters: Deep Implicancy," a film by Denise Ferreira da Silva in collaboration with Arjuna Neuman.

- Climate Justice Code (Utrecht: Casco Art Institute, 2023).

- 4 Waters: Deep Implicancy.

- Anja Groten, "Workshop Production" in Figuring Things Out Together. On The Relationship Between Design and Collective Practice(PhD diss., Leiden University, 2021).

- Stengers, In Catastrophic Times, 62.

- Sara Ahmed, What’s the use? On the uses of use (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 10.

- Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway. Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham, London: Duke University Press, 2007), 91.

- Katherine McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 164.

Otherwise Possible Connections

A conversation with IPOP

(In Pursuit of Otherwise Possibilities, Elioa Steffens and Szymon Adamczak)

Tuesday, 17 December 2024

At the GRA/SI, material-based research and learning about and through making takes place across departments, workshops, and facilities, and thus plays a crucial—though often under-articulated—role in art and design education. One focus of this conversation is on understanding how embodied knowledge is transferred in educational settings and how collective material engagement shapes learning processes.

Through the support of the CoECI grant, it was possible to invite collaborators to join the project, such as IPOP (In Pursuit of Otherwise Possibilities), an educational artistic research platform exploring how educational institutions can better foster queer artists and their practices. By involving IPOP, we aimed to bring together the different registers and vocabularies of embodied knowledge-sharing, while also catering to the interests and sensitivities of a diverse student body that does not adhere to educational structures rooted in heteronormative and colonial art and design histories.

The collaboration aimed to connect existing efforts at the academy around material-based research, giving special attention to developing a collective and inclusive approach to making those resources and practices accessible to the community—with additional support from IPOP.

A key consideration was the role of workshop-based education within institutional structures. Despite its significance, the workshops often occupy a subordinate position in relation to curricular education, both in terms of decision-making power and resource allocation. We were interested in the potential of IPOP’s work on queering feedback to challenge these structures.

The BB (Bookbinding Workshop) team was invited to join this collaboration due to their collaborative and interdisciplinary approach as well as the toolkits they developed to put anti-disciplinary practice in motion. By offering students the chance to take the tools and materials into spaces other than the workshop itself, they challenge the idea of a workshop as an exclusive and expert-driven space for material production. We wanted to use the collaboration to expand the mobility and spontaneity of workshops and labs, including their equipment.

Both BB and IPOP’s practices are built upon collaboration and offer a unique perspective on the intersection of embodied practice, needs-based pedagogy, and vulnerability in artistic production. Their methodologies embrace open-ended, often uncertain creative processes.

This conversation delves into these questions, examining the ways in which teaching methodologies through embodied practices can reshape pedagogical frameworks and intervene in existing hierarchies. It is a collective reflection on different moments of the collaborative process and not always in chronological order. It was held a month after the workshop took place. What preceded the workshop were several online and offline work sessions during which BB, IPOP, and ourselves (Anja Groten and Márk Redele), got to know each other and each other’s ways of working, and developed a conceptual framework that took glue as a material and conceptual framework as a starting point. Glue allowed us to explore the relational aspects of material-based research through the lens of situated and collective learning and transfer of embodied forms of knowledge. In IPOP’s publication Queering Artistic Feedback, Antje Nestel asked, “What if there is no work/object [yet] to give feedback on?” In our sessions, we developed this thought further in light of emergent hands-on learning and collective forms of knowledge production.

BB offered a material framework and guidance to produce various types of glues from scratch while IPOP guided us in evoking glue’s performative potential.

Participants were first year students of the Design department at Sandberg Instituut as well as two additional participants from the network of IPOP.

A day prior to the workshop, IPOP gave the artist talk “Otherwise Possible Connections: Queering Artistic Feedback,” as part of the Unsettling Bar moderated by Emirhakin. The talk was open to everyone.

As part of their contribution to the workshop, BB invited Vic Hoogstoel from the silkscreen workshop who introduced us to the legacy of the GRA billboard, a 430 cm x 122 cm panel installed in front of the academy, which is a place for students and staff to announce, exhibit, and publish. It was initiated by Kees Maas, the previous workshop manager of the screen printing workshop. For the glue workshop we decided to utilize the billboard as a performative space, and rather than focusing on what we pasted on it we focused on how we paste on it, thus the glue became the focal point.

Aside from experimenting with glue-making and learning about its material properties and performative potential, we did movement and mapping exercises. The following exercises are mentioned in the conversation:

- Warm-up exercises: Group moves through space, following different prompts to change speed and taking notice of each other

- Sticky feedback: Free writing exercise on stickiness of personal experiences with Feedback

- Mapping: Create individual and collective maps of feedback experience(s)

- Hands-on glue making

- Hijacking the glue

- Body voting: Collective decision making on how to approach the billboard

- Billboard exercise: Activating the glue on the billboard

As the finishing act of the two-day workshop, Lila Bullen-Smith, an artist, designer, and Sandberg Instituut alum, prepared and facilitated a delicious, sticky dinner, which served as an act of collective reflection and sharing. Lila is a member of the Brackish Collective, which explores food as a medium for storytelling and socio-ecological inquiry. They employ hosting, tasting, and eating rituals as alternative tools for accessing socio-political knowledge embedded in our environment. Their work often involves site-specific research, leading to immersive installations and performances that invite audiences to engage with the history of particular ecological sites.

Lila proposed the meal as an extension of the workshop’s themes of material-based engagement, exploring the stickiness of social gatherings over food and drawing a connection to the glue. The dinner featured a recipe-writing exercise, where the participants wrote and exchanged recipes as a form of “feedback,” aligning the act of sharing food with the workshop’s process. These contributions were gathered and are compiled into a small cookbook.

Beyond the recipes, the dinner itself was designed as a participatory experience, drawing attention to the textures, flavors, and labor of cooking as sites of material exploration. We had bread and butter, artichoke with preserved lemon, mayonnaise, onion galette, salt-baked beetroot with whipped ricotta, apple and hazelnuts, salt-baked carrots with orange-butter and sage, drunken prunes, and rice pudding. We drank blackberry and fennel soda, and strawberry and verbena soda on the side.

Anja Groten and Márk Redele

Hi, and welcome Elioa and Szymon. Could you introduce yourselves once more and tell us about your backgrounds, and also the background of IPOP?Elioa Steffens

I’m Elioa Steffens. I’m from the U.S., which I think has a significant impact on how I engage with art, education, and particularly with IPOP. My mother worked at a theater, and I started participating when I was eight. I continued consistently throughout high school, where I also became involved in youth organizing, primarily focused on addressing harassment targeting LGBTQ students in my community. This work was a kind of return to community for me. I grew up on an island and left for high school due to the harassment I experienced at 13 or 14. When I found activism, I felt that if I was going to critique my community, I also needed to support efforts to change it. The organization I joined was entirely youth-run. We had one adult employee, but the board consisted entirely of young people under 22. There was a strong emphasis on empowerment, facilitation, and learning how to hold space and lead meetings. It was highly educational, though at the time, we rarely used terms like "education" or "pedagogy." This has been important in shaping my approach to IPOP. I’ve always approached education somewhat sideways to the institution, in that I’m deeply aware of politics, systemic structures, and their impact on people, but never seen education as a rigid, nine-to-five system with structured classes and curricula. In college, I studied theater and explored ideas of community, which has always been a central interest of mine. Afterward, I joined an organization that used the arts to provide life skills and empowerment for teenagers. During this period, my artistic engagement shifted from focusing on production, product, and craft to centering on affect and the craft of facilitation, with art serving as a tool rather than an aesthetic goal. I was trained in a facilitation approach called the Creative Communities modality, which placed a strong emphasis on mastery, developing high-level skill in facilitation. This has been a key influence on my work with IPOP. From the beginning, we were clear that we wouldn’t hire artists who didn’t know how to give workshops. We don’t assume that being an artist automatically means knowing how to educate. Many artists are also skilled educators, but these are distinct skill sets. I wasn’t interested in the model where an artist simply presents their work to students and calls it education—especially when they’re not good at it, and plenty aren’t. Another important aspect of IPOP’s development, and something we’ve been reflecting on recently, is how idiosyncratic our methodology is. It’s shaped by who we are as people, and that’s significant. This extends to the people we co-research with, the participants we engage with, and those we’ve brought in through various collaborations. It’s a deeply personal approach—whether that’s beautiful or not is up for debate, but it’s worth acknowledging. Shall I introduce IPOP?AG

Yes, that would be great.ES

We are an educational artistic research project, posing two key questions: How do we support queer people in the academy to advance? And how do we support the education of queer artists? While much of our focus has been on students, we have also been deeply interested in supporting staff and teachers, aiming for a more holistic understanding of what it means to create, to think of an audience within the educational frame, a queer audience. And then the other part of it was the question of how this work of supporting queer individuals within the academy and arts education contributes to the broader landscape of arts education itself. While we initially worked within academic institutions for structural and funding reasons, we have always been interested in breaking down the division between the academy and the larger ecosystem that supports artists beyond it. Over time, we have expanded our work into residency spaces, festivals, and collaborations with individual artists, often acting as dramaturgs and facilitators. In our first year, we ran several programs, including workshops, a reading group, and what became known as the queer feedback sessions. These sessions evolved into a seven-week program (spread over non-consecutive weeks) in which a cohort of queer artists came together to share their work and provide feedback. We developed an experimental approach to feedback—creating individualized, need-based protocols tailored to each artist and session. At the heart of this work is the belief that feedback should be fundamentally and necessarily for the artist. Within the IPOP model, feedback time is structured to serve the artist’s needs first, allowing them to shape the process in ways that truly support their creative practice. We have also used this work to critique and reflect on how the academy functions, as well as the broader ecosystem that supports artists, including the ways in which it doesn't work. So, I wonder about what minor interventions we can make.Márk Redele

Szymon, do you want to introduce yourself as well?Szymon Adamczak

I’m Szymon Adamczak, my work exists at a crossroads—blending and engaging with resources and knowledge from the U.S., Poland, and the Netherlands, where our project is based. This transnational exchange of queer thought and artistic practice has been central to IPOP, shaping our approach and expanding the project’s intellectual and creative foundations. I did not initially train as an artist. I entered the theater world as a self-taught practitioner, which was a formative experience—observing both sides of the stage, analyzing audience reactions, and understanding the dynamic feedback loop between performance and spectatorship. My early work was shaped by a liberal arts education, community organizing, and involvement in civic movements in Poland before I eventually professionalized within theater and performance-making. My first formal art school experience was at DAS Theatre in Amsterdam. This period coincided with a time of intense political conservatism in Poland, marked by openly anti-LGBTQ+ policies. Living abroad, I felt a strong personal and collective need to understand queer identity and the social and political repercussions that came with it. These experiences deeply influenced the ideas I have brought into IPOP—particularly the urgency of community survival and the belief that rather than waiting for institutional support, we must create our own networks of care. Another key influence on my work has been HIV activism, which intersects with education in meaningful ways. While studying I was diagnosed and I became engaged with learning about the history of HIV/AIDS activism. However, I quickly realized that much of this knowledge was absent from art schools and had to be sought outside academic institutions. This gap underscored the necessity of IPOP for me—the dream of a space where queer pedagogies and embodied knowledge could have a presence within the academy. Knowing that LGBTQ+ students exist within these spaces, it felt essential to cultivate an environment that acknowledges and addresses their specific needs. My practice now revolves around dramaturgy and artistic research, and IPOP serves as a way to bridge artistic research and pedagogy, in which I treat education as an extension of artistic practice. I see IPOP not just as an educational research project; it is an evolving practice that critically examines and intervenes in institutional structures. A significant part of our work involves tracing the lasting effects of different feedback modalities—understanding how they live in artists’ bodies and how they shape artistic development over time. Through IPOP, we make space for these embodied experiences, incorporating a somatic awareness in our approach. We frequently collaborate with choreographers who help us explore these dynamics through movement and bodily engagement. A core aspect of our methodology is co-designing individualized feedback protocols with artists, ensuring they have agency in shaping their learning experiences. Through this, we hope to empower artists and help them reflect on past experiences, build nuance in their practice, and develop the confidence to effectively articulate and advocate for what they need. Ultimately, IPOP is about more than just feedback. It is about creating a sustainable framework for queer artistic education, fostering self-determined learning, and ensuring that queer voices are heard and supported within and beyond the academy.AG

A key point that resonates with me is the blurred line between artist and educator. For a long time, it was simply taken for granted that artists could also be educators. But we’ve had to come to terms—sometimes painfully—with the reality that teaching is a skill in its own right, and artistic ability alone does not automatically translate into effective pedagogy. Recently, however, more artists view facilitation and education as integral to their practice rather than a separate role. While financial necessity once pushed artists towards teaching, many now embrace pedagogy not just for income but as a meaningful extension of their art and design practices.ES

I think I both agree and disagree. I’m not entirely convinced by the economic argument. In fact, I’d say the financial situation for artists has become even more precarious, pushing more of us into education out of necessity. Many artists I know who teach do so not because they see it as an extension of their practice, but simply because it’s one of the few ways to earn a stable income. As a result, teaching has become a much larger part of what we actually do on a daily basis. That said, I’ve noticed a shift in how artists approach education. In the past, some would lead workshops focused mainly on their own work, and only occasionally engaged with students—essentially just sharing their practice without much consideration for pedagogy. I see less of that now. That’s less common. Cultural expectations have also changed—there’s less tolerance for the “grand artist” persona, where someone teaches without any real responsibility to students. I’ve even seen artists show up intoxicated, but such behavior once excused by status or reputation is far less acceptable today.SA

Yes, exactly. One of the core aspects of IPOP is the development of custom-made feedback methodologies, tailored to the needs of each artist. Rather than applying a one-size-fits-all approach, we work closely with artists to understand what they are actually seeking in their practice and what kind of feedback would be most useful to them. An example that comes to mind is when we collaborated with an artist whose work was deeply rooted in somatic experience. Traditional critique sessions, where discussion is primarily verbal and analytical, weren’t particularly helpful for them. Instead, we designed a feedback structure that prioritized embodied responses—where participants engaged physically with aspects of the work before reflecting on it in words. This shift allowed the artist to gain insights that resonated more with their process, rather than being forced into an external framework of evaluation. In this way, facilitation and artistic practice merge, as the learning space itself becomes an extension of the artist’s creative inquiry. By embedding feedback methodologies within artistic practice rather than imposing them from the outside, we try to create a space where artists can refine their work on their own terms while still benefiting from collective reflection. A key part of our approach is questioning the supposed universality of feedback and facilitation methods. There isn’t a single recipe that works for everyone, and we’ve consciously chosen to diverge from established models—such as the DAS Theatre feedback system, which has certainly influenced us, but which we also felt the need to move beyond. Our focus is on following the needs of artists as they arise, embracing experimentation, and seeing each feedback session as an opportunity to learn rather than a rigid structure to be applied universally. One of the crucial aspects of this process is recognizing how power dynamics operate within a learning space. Facilitation, even when thoughtfully executed, can still reinforce hierarchies or allow certain voices to dominate. That’s why we place such emphasis on fostering an environment where feedback is reciprocal, where authorship and authority can be questioned, and where learning happens collectively rather than being centered solely on the advancement of individual artists. We aim to create a space where contributions can be picked up, reshaped, and expanded by others—where knowledge circulates rather than being owned. This becomes especially significant in a performance context, where embodiment plays a crucial role. A strong example of this came from our work at SNDO over the past two years. One artist we worked with was exploring grief in their choreography, and instead of offering verbal critique, the group engaged in an embodied response. Participants shared the ways they personally grieve—through movement, through specific gestures, through bodily expressions of loss. This process allowed the artist to learn not just through discussion but through direct experience, by witnessing and engaging with the many ways grief manifests physically. In moments like this, feedback goes beyond analysis; it becomes a form of shared expression, a deeply generative and transformative exchange.

AG

It seems so obvious now that how we share feedback is just as important as what we share—the information itself. For example, the idea of whispering feedback is really interesting. In this case, the artist is working with whispering as a research subject and is able to turn it into a feedback methodology. The feedback methodology and the moment of sharing then become an extension of the work, while offering new insights. I find this example inspiring, not because I'm specifically working on this topic, but because it serves as a reminder for me as an educator that we can't just settle for our methods. It's not about standardizing a best practice. I think with IPOP, there's been a resistance to creating set "recipes" for feedback that others can just adopt. However, I also find it really helpful to hear concrete examples. In our process I particularly enjoyed going through some exercises with you, writing them down, and thinking about how they can be adapted or used in different contexts. I'd be curious to hear more about your thoughts on feedback methods—how they can be disseminated and moved between different contexts, how they might be shared across various environments.ES

We’re working on a book, and in it we make a distinction between techniques and methods. Loosely, techniques are activities, while methods are more about structure and philosophies. I mention this because I find myself curious about the extent to which methods can be shared. There are definitely aspects of methods that can be shared, like the questions we ask and the value system we engage with. No skill is uniquely ours—neither of us hold any skills that others can’t learn. But I do think that much of how we share methods is through a description of context, who we are, our skills, the questions we ask, the values we hold, and the outcomes we’ve had. It's kind of a real desire to ask: hey, what is actually true for you, and how do you know? As for techniques, I think they’re actually quite shareable. In the book, we’re writing out a lot of techniques in a “how-to” format. What’s interesting is how the techniques and methods can meld. I’m curious about how this will work in the book and maybe something we should revisit. In some of the ways we encourage people to play with the techniques, we’re also sharing the method. We’re saying, “This is how we do it,” but pointing out the places where there’s flexibility. Of course, people can adapt them as they wish, but we’re trying to show that a technique can take 20 minutes or two hours, and it can work with one person or a group of 50, and here’s how it might look in each case.SA

In terms of sharing methods, prompts, and community knowledge, we're also guided by feminist principles and lineages, right? We strive to uncover where we learned from, who taught us something, and what we do with that knowledge. We aim to show that our practices are not about inventing the wheel but rather building on a continuity of ideas and teachings. However, we also challenge the notion of authorship and the idea of “trademarking” knowledge. Instead, we seek ways for these practices to circulate, be picked up, and adapted by others. There's also a tension I feel, especially coming from Eastern Europe, regarding the use of terms like “feedback” and “performance.” These words are often tied to business, capitalism, and productivity, which can complicate their usage, especially in contexts outside of the West or Global North. For instance, when translating or exporting ideas from the Global North into other contexts with different historical developments or cultural traditions, there’s a risk of positioning these ideas as superior. I’ve noticed this, especially when teaching in Poland, where the theater culture differs significantly. The discourse around feedback, for example, can take on a different agenda for younger artists. For them, feedback can become a system that protects students from violence or top-down authority, acting as a mediator between students and professors. Additionally, we’re listening and learning from global movements, like Black Lives Matter and Palestinian solidarity movements. These movements, along with the broader calls for body autonomy, influence our thinking. We’re aware of how the external world is reflected in the classroom, and how facilitation plays a role in addressing these issues in our teaching and practices.AG

We invited you to work with us, to engage in conversations, and develop workshop situations together. Our starting point was material-based research and education, embodied forms of knowledge production, and learning. One key element of our research trajectory was to really focus on the workshops as sites of material inquiry but also as social environments in which knowledge is shared. We felt that this aspect of art and design education is sometimes neglected. It's crucial to students' development, yet there can be a lack of appreciation for what happens in these spaces. We proposed collaborating with IPOP and developing a workshop together with the BB Workshop at Gerrit Rietveld Academie. Márk, can you recall why we chose this particular workshop? It may not seem like the most obvious choice at first glance. For someone unfamiliar with our bookbinding workshop, it might seem surprising.MR

We were interested in BB because of its focus on producing personal toolsets, which are primarily designed as educational tools but also serve specific purposes for bookbinding techniques and other publication-making practices. The BB team develops DIY methods for creating solutions that can be shared openly, allowing students to create their own tools. This enables them to set up their own emerging studios or workshops, where they can produce books or publications at very low cost and in an accessible manner. We were intrigued by how the methodology of creating these toolsets facilitates communal, material-based knowledge sharing. It's collaborative in nature, focused on openness and making things open-source. Additionally, it relies heavily on iterative learning, where students test tools, learn from the outcomes, and refine their methods. Another reason we were drawn to BB was its ability to simultaneously engage with both the materiality of a book and the content it holds. This intersection of material and text is exciting, as it allows for the exploration of both physical craft and conceptual content in one practice.AG

BB, in many ways, challenges the boundaries typically established by institutions. They push and question assumptions about where the workshop production should take place. BB have expanded beyond these infrastructural confines of their space—they work across different spaces, other workshops, classrooms, intervene with students in the library, and they even travel internationally to share their practice in other art academies abroad, i.e. recently Yale in New Haven and Tufts University in Boston. Through these activities, they've developed a unique collective practice that goes far beyond just being a service provider sitting in a workshop, waiting for students to come by with their questions. A key focus of both BB and IPOP seems to be on empowerment and it was really rewarding to see how that took place in the workshop we facilitated together. It felt like a mutually empowering experience for both students and facilitators. I am curious about your experience working with the BB workshop. I'm sure there were surprises or unexpected moments in the process. I’m just really eager to hear about what it was like for you, both in terms of the preparation and how the sessions unfolded.ES

In my experience working with BB, I found them to be deeply conceptual and it made me confront my assumptions about craft-based work and conceptual work. Maybe that distinction is artificial. My experience working with them was really interesting and quite different from how I usually work. There were definitely moments of faith—just going with it and seeing how things unfolded. I also find it fascinating to think about education in terms of outcomes. How do we define the value of education? Is it tied to a specific result or effect? Looking back, what really stood out to me was how enjoyable and abundant the process felt. That abundance is something worth highlighting. In many of our teaching experiences, we work in pairs, which is relatively unique. But even then, it can feel like you have to be “on” the entire time, fully engaged. Working solo can heighten that feeling. In contrast, having seven leaders in this context created moments of ease. There were times when I could just play with glue and chat with people, which felt different from the usual structure. It also influenced our values around non-hierarchical structures in an interesting way. Not only did we talk about being equal, but we were actually engaging in the same activities—experimenting together, side by side. That shift created more space for true non-hierarchy than I’ve experienced in many other programs. In most teaching moments, even when I’m actively participating, I always have one eye on the bigger picture—making sure everything is running smoothly. But in this setting, I could let go of that for a while and then step back into it. There was also something inherently generous about the materials and equipment. BB, in particular, had tools they could share freely, which was beautiful. There’s something special about cutting paper, seeing the physicality of it, and working with those tangible materials.SA

First of all, it was a really great experience collaborating with the BB team. The vibe they bring, their groove, I really love their way of working. When they shared their projects and interventions, I found that really inspiring. For example, the way they responded to the COVID-19 situation with a WhatsApp phone hotline or the mobile bookbindings toolkits in bags they created for people to take. Those were really thoughtful gestures. It was also important to witness different approaches to workshop preparation. We tend to be more conceptual, working with scores and duration, focusing on the experiential aspect. In contrast, with bookbinding, the material itself seemed to dictate what was being experienced, which was an interesting shift. What I really enjoyed was how we all allowed the process to take the lead in our exchange. There was this tension between the process and working with a specific, historically significant site—the mural, the billboard—that had been chosen by the BB team as the format we work towards. I also found it exciting how multilayered the inputs were. We had a historical presentation on the billboard, our own presentations, discussions, and the team’s contributions. It created this multi-directional flow of information. I hope it didn’t overwhelm the students, but rather encouraged them to follow what interested them most. Later in the process, even though we were working professionally, things started to materialize organically. There were moments of uncertainty, like, how do we step back? Who is doing what? But that openness and trust in the process were really valuable. There wasn’t a strict division of labor; instead, things happened voluntarily and spontaneously. I really enjoyed observing these micro-interactions, whether it was people meeting over the glue, the mapping sheet, the billboard, or even by the microwave. There were so many of these small but meaningful exchanges. One of the most powerful parts for me was the body voting. As IPOP, we had never used it so extensively before. It was fun, exciting, and sometimes exhausting seeing how decisions played out, how aesthetic choices were debated. That whole process, the complexity of it, was really revealing. It became an interesting act in itself, regardless of the final outcome. Lastly, from the perspective of IPOP, I really appreciated the status of the BB workshop within the institution. It’s a team that is rooted in the building, and serves students, alumni, and others. There’s something about that kind of space-making that we don’t necessarily have in the same way, since our activities are structured differently and more spread out. It was nice to tap into that.

MR

I’d like to add something about disciplinarity and anti-disciplinarity and how, to me, there seems to be a connection between facilitation and feedback methodologies that can guide us from one to the other—or rather, from one territory to another. This became particularly clear to me throughout this workshop. When I think about conventional disciplines—architecture, for example, which is my background, but also performance or graphic design—the typical modes of interrogation, often referred to as feedback in education, tend to focus on identifying what aspects of a student’s or participant’s work don’t belong to the discipline. There’s a lot of negation involved, a process of filtering out elements deemed unnecessary in order to maintain a narrowly defined tradition at the core of that field. What I experienced in this workshop, however, through the feedback methods you introduced, was a completely different approach—one that felt incredibly generous and inclusive, considering every contribution without exclusion. And because of that, by the end, it almost became impossible to define exactly what discipline we were left with. Even though we started with a clear framework—a bookbinding workshop, working with the glue and publications—once we engaged with these feedback methodologies, the boundaries of that discipline began to dissolve. Not in the sense that the foundation disappeared, but rather that a transformation took place. This process clarified for me what we mean when we talk about anti-disciplinarity as something desirable or valuable. There’s a clear dynamic between disciplinarity and anti-disciplinarity, as well as between conventional interrogation techniques and alternative feedback methodologies. I sense a meaningful relationship here, one that shifts how we understand and navigate disciplines.AG

I think it might also be related to the fact that we didn’t work on a book in the traditional sense. The book wasn’t the central focus; instead, it was the glue that was the focus and held everything together, metaphorically and literally. This shift opens up all sorts of other possibilities. Usually, glue is a material that isn’t meant to be noticeable—it’s there to serve a specific function, but you don’t spend much time thinking about what type of glue you’re using. When that becomes the main focus, it helps break down some of these disciplinary assumptions.MR

At the same time, I’m really curious about how this workshop would have looked if we had considered a book as the goal.ES

I know a lot of folks often feel the need to defend their placement within a discipline. This seems to be especially important in the Netherlands. Coming from the U.S., it feels wild to me because we don’t have the same kind of funding, so it doesn’t matter as much whether you call yourself a visual artist or a performance artist. Here, however, it’s a more defensible position—if you want funding from the Dutch government, for example, you really need to prove that you are a visual artist. I think this also applies, though to a lesser extent, to the performing arts. This idea connects to the concept of queering. For us, it’s not that discipline isn’t important, but we want to be really clear about why and how we choose that identity. It’s not that we don’t care about discipline, but we don’t let it limit us. We come from the performing arts, but we’ve had visual artists and filmmakers participate as well. Discipline isn’t a barrier for participation, but it does matter in some ways—we consider it when thinking about how we show up in relation to the work and what it means. We think about the histories of those modalities, but we don’t want to say that discipline is never important. In some contexts, it actually is incredibly important, especially in terms of career advancement. What you're saying about finding ways to lessen the importance of strict discipline boundaries is really beautiful, because it allows for more choice and a recognition of how limiting it can be. It also opens up a space where we can point out the absurdity of certain moments when discipline becomes important for reasons that don’t really make sense. Personally, I think I’ve been fairly clear about wanting to think in a multidisciplinary way, but I know classmates and peers in other institutions where this issue is a key factor in evaluation. It’s not uncommon to hear, "We don’t know how to evaluate you because you don’t fit within a clear discipline.” To push back against that, on both a political and values level, it feels important to ask, “Why is this the case?” It’s messed up, unless you’re really trying to teach something about how you engage with a system that upholds such boundaries. I think that’s something I appreciated about this workshop. I’m also curious what it would have been like if we had actually set out to make a book and what kind of book we would have made. For me, there’s also this interesting tension that emerged in the group about whether or not we were making a coherent product. Many participants struggled with the idea that the outcome was so amorphous and were uncertain whether it would be valuable to an audience. It made me think about how, sometimes, we might not even know the value of something until later.AG

What you said earlier about abundance really resonates with me. Normally, as an educator, I’m in charge and feel responsible for running the show, making sure everything’s in motion. But this time, I felt very grateful to be with my students in a different way. A lot of the people joining were students I work with every week, and I could engage with them without having to be the one in charge. It allowed me to encounter their way of working and thinking in a completely different way. It’s always my goal when I teach to create a space without hierarchies, where we all share the responsibility of holding that space. But still, there’s a difference between joining in as a participant and encountering the students during an exercise like the one you led. Walking around the room and sharing intimate stories with each other was a unique experience. The body voting exercise was also incredible. It gave me important insights and material to think about and continue working with, especially regarding how we make choices.

SA

I'm also curious, as educators running a multi-workshop program, what you sensed from your students. What do you think happened for them? What did they say about the experience?AG

It seemed to me that the students felt like they were part of something really special, and it seemed very precious to them—not just in terms of the experience itself, but also in the content of what they were exploring. They had the opportunity to zoom in on how they learn, to ask themselves, “What do I need?” They had a chance to figure that out for themselves and to develop the language to express it. That preparation will be valuable as they enter their upcoming classes and meetings with tutors, giving them more agency in their own learning. I can still feel the impact of that session with the first-years, and I think they did too. Having that space to talk amongst themselves was important. It was also a rare opportunity for them to meet the workshop facilitators in such an in-depth way. Normally, they just get a tour of the workshops and are left to find their way. But having Vic Hoogstoël from the silk-screen workshop present the billboard and its history was really special. And beyond that, simply getting to work with people for a longer period made a huge difference. Speaking about abundance, it felt like such a special moment to have several interesting educators and facilitators around, who were truly present for and with the students. That’s not something we usually do, and I think a lot of that has to do with the scarcity of resources. But it really stood out. I think this was true for the other workshops as well. Bringing people together from different departments and disciplines is so rare, yet it was clear how much everyone appreciated learning from each other, not just as students but as facilitators and educators too. That kind of cross-learning is something we don’t often make space for, but when we do, it’s incredibly valuable.MR

One thing that really stood out to me, and touched me deeply, was how, in most individual projects, a person's executive functioning often determines how successfully they can take on a challenge. But in this workshop, from the very beginning, I saw a different dynamic emerge. There was such a generous, communal aspect—not just in terms of sharing resources, but also in the kind of attentiveness and gentleness required to navigate these feedback methods. This created an environment where people became increasingly comfortable throughout the day, feeling empowered to take initiative and make decisions on their own. That was incredibly special to witness, and I think it’s extremely valuable, especially in a setting where improving that kind of confidence and agency can be quite difficult. And on another note, though we joked about the dinner, I overheard a first-year student say, "This is the first proper meal I've had since arriving in Amsterdam." That really stuck with me because, for many people, that’s a reality. Creating these generous spaces, where care and nourishment extend beyond just the learning process, has a real impact—not just in the moment, but in a broader, developmental sense as well.SA

Wow, that dinner was amazing!AG

It was really delicious. I’m still thinking about it!ES

I’m really grateful for the experience, it was great to be a part of it. The people who came from outside were really valuable to the dynamic. There were only a couple, but they made a big impact. The dinner was really beautiful, and it made me think about something we try to focus on—something that Szymon, you often bring up better than I do—the importance of addressing basic needs, like food, water, and breaks. It’s easy to overlook these things, especially when we’re creating a space that feels caring. But having snacks and a meal like that is such a huge part of creating that atmosphere. For me, sometimes I forget, in the hustle of my own material and social life, that not everyone has access to what I might take for granted. For some people, this could have been their only or most significant meal of the day, and I’m reminded of that.MR

Thank you for the reminder. This feels like a natural moment to wrap up. Thank you so much for both of you.

Speaking Out Loud With Fungi

A conversation with Sam Edens

Wednesday, 18 December 2024

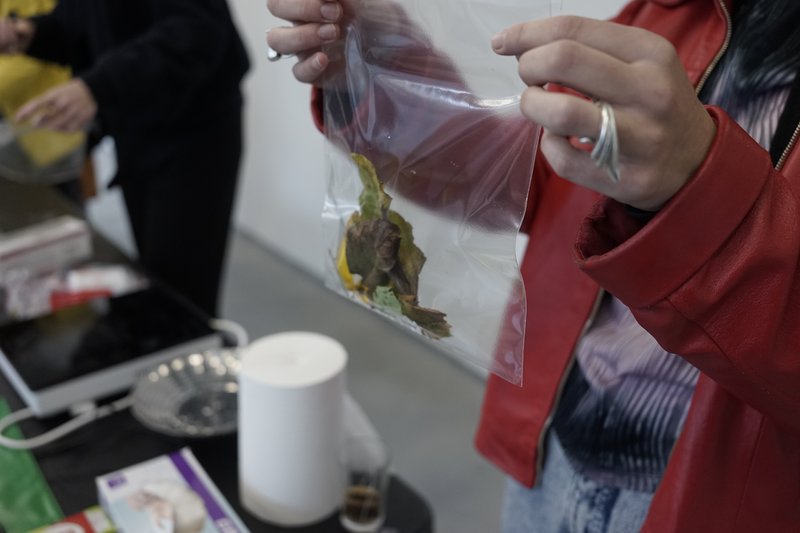

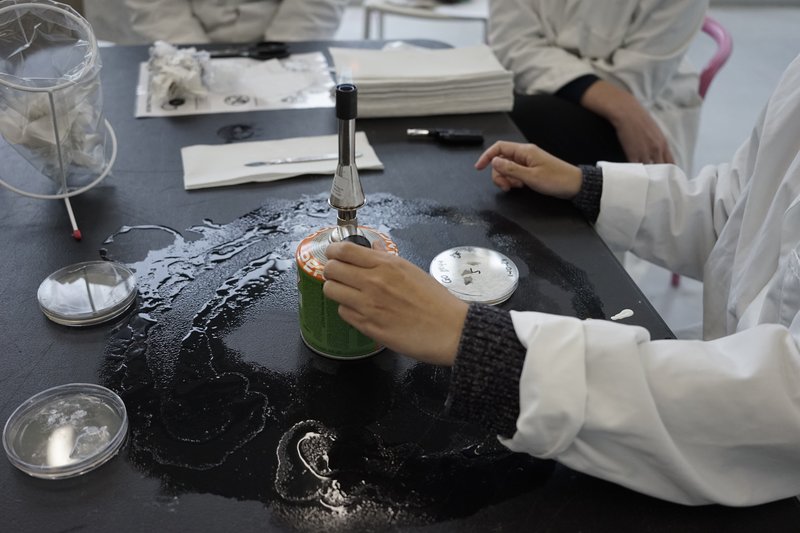

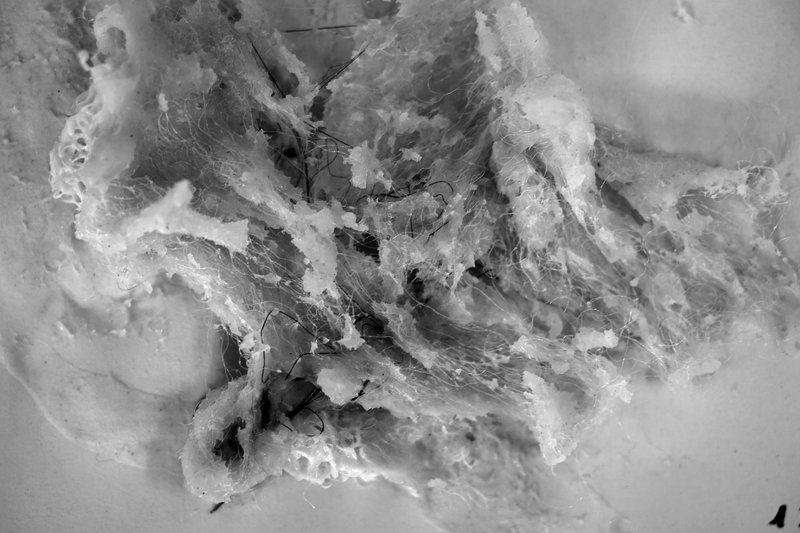

In this conversation, Anja and Márk invited Sam Edens to join them in a collective recollection of, and reflection on, the workshop “Entangled Fibers: Grey Oyster experiment.” The event brought together the students of the TXT department, the Garden Department, the HvA Biomaterials Studio, and the Design Department, as well as other living organisms.

Sam Edens (HvA) is a bio-designer and researcher with experience working with bio-based and living materials such as fungi, algae, yeasts, and bacteria. The workshop guided students in cultivating Grey Oyster fungal threads on substrates of decaying materials from the garden. The collaboration between the TXT department, the Garden Department, and Sam’s expertise aimed to foreground how knowledge emerges from the interplay of materials and the environment in a collective, material-discursive setting. With theory intermissions by Giulia Damiani (theory tutor at TXT), and workshop specialist Mathild Clerc, we explored how material-based research can resonate in collective learning and embodied forms of knowledge production.

Workshop outline

Gathering in the Garden

Introductions by Sam, Anja, and Márk

Presentation and tour by the Garden Department

Giulia introduces first thoughts on relevant theoretical frameworks

Collecting materials from the garden for growing the substrate

Sam introduces lab safety and creating sterile working environments, work in closed space (with view on the garden)

Theory intermission #1 by Giulia

Lunch break

Theory intermission #2 by Giulia

Working in closed space (with view on the garden), led by Sam

(If there is time: Theory intermission #3 by Giulia)

Wrap up

Cleaning, sterilising

Anja Groten

Sam, it's nice to have this conversation not too long after our workshop to recollect and reflect on the experience, and perhaps follow up on some of the questions that came up. The invitation for you to join and develop a workshop alongside the TXT department came from our shared interest in exploring materiality and material-based research through the lens of living organisms and unstable matter. We wanted to think about the laboratory, both conceptually and practically, especially since we don’t have access to such a space within our academy. A lab feels like a more controlled and sterile environment compared to a typical art school workshop for instance, yet these spaces share some similarities, for instance the experimental character of the activities that take place in them. We were particularly interested in how to navigate such a lab space in an educational context and in your experience with that. In our preparatory sessions, we considered materials that were interesting both physically and conceptually for a workshop setting. We’d love to hear more from you—about your work, and how you established the Biodesign lab.Sam Edens

My job mainly involves coordinating the Biomaterials Studio, teaching about biomaterials in the minor Sustainable Futures and other programs, and working with living organisms. I also spend two days a week as a researcher in the Circular Architecture Research Group, focusing on bio-based and regenerative building materials. My work is split between the technical properties of materials and designing with living organisms and bio-based materials. In the Biomaterials Studio, we essentially run a community bio lab. It's open to students, researchers, and lecturers, but in practice, it requires someone to assist, which can be challenging with the small budgets we have available. During classes, I teach students how to work with different organisms, emphasizing the need for safety, protocols, and understanding each organism’s specific needs. Another focus is developing new materials that could replace fossil-based plastics—something very experimental, but it's particularly appealing to students at a fashion school.AG

When you say experimental, do you mean that something is not necessarily for immediate application or immediate use for the industry? Rather than solving problems, it's about seeing what can be done through a process of trial and error?SE

Well, the Amsterdam University of Applied Science (AUAS) trains students to work in the industry. I work specifically with students from design fields like fashion. Our lab is small, so the work we do is experimental and not scaled for commercial bio-based material production, like mycelium leather or bacterial dyes, which are produced at an industrial scale. I mean, there's a huge difference between what we can do in a lab and actual industrial-level bio-fabrication. However, to understand industrial processes, you need some knowledge of microbiology and design. I aim to help them understand processes of how to fabricate these materials, how the fields of microbiology and design intersect, even though we can't replicate industrial bio-fabrication in our lab. In a design school, working with living organisms and regenerative materials is more about exploration—how to collaborate with organisms and create materials together. In industry, bio-fabrication and bio-engineering focus on genetic modification, and optimizing and isolating organisms. The vocabulary and skills involved are quite different. When I teach design students about working with living materials, I’m introducing them to the practice and its vocabulary. However, I don’t have the resources to fully train them for bio-fabrication; that requires a separate program. My goal is to ensure they can have meaningful conversations with microbiologists and bioengineers.AG

In our workshop, we involved Giulia Damiani, who is a writer, researcher, theater-maker, and theory teacher at TXT. Giulia introduced the theoretical concept of new materialism and how artists relate to fungi. She highlighted the growing interest in these organisms in the arts, noting their uncontrollable nature and ability to thrive in damaged environments. Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing has been read and discussed a lot in the field of arts and design. Mycelium’s unstable characteristics have sparked the curiosity of many artists, not only as a material but also in how we engage with art in more fundamental terms. Given your experience, Sam, I’m curious if you've observed this trend as well. Why are artists and designers increasingly drawn to mycelium? Beyond the practical benefits of regenerative materials and reducing waste, there seems to be a more philosophical or fundamental fascination with mycelium.SE

Well, if you start working with living organisms you have to rethink what a material actually is. Unlike traditional materials, which are controllable and passive, living materials require a different approach. It's another type of relationship you build with the material, one that allows for a sort of dialogue. Working with living materials challenges how we relate to materiality, especially in environments like AUAS. You know, when we are talking about wood we tend to talk about functionality. But we're not really talking about its behavior and the way it interacts as an active agent. New materialism discusses material agency, and when working with living organisms, that agency becomes undeniable and experiential. It forces you to adjust your approach, which can be both fascinating and frustrating, but ultimately, it changes the way we interact with materials in a way that other materials don’t.Márk Redele

I’ve been thinking about the situatedness of these materials and how they’re often removed from their original context when they are brought into labs. The shift toward new materialisms seems to reflect a desire to reconnect with the environments where these materials come from. It’s about exploring where they live and the conditions that allow them to maintain the properties we’re interested in. Maybe that resonates?SE

Yeah, looking back at, for instance, the minor in Sustainable Futures that I have been coordinating together with Ista Boszhard (co-founder of TextileLab, Waag), I think our workshop captured what we aim to do there as well—practical work with organisms alongside philosophical discussions. In the minor we also focus on critical thinking and reflection, helping students who want to work with materials differently and perhaps engage with it more critically, but don't know where to start. A question we are interested in is how to engage more critically with material while industries may not seem aligned with our values. This combination of hands-on material work and understanding its broader context helps students bridge gaps between thinking and making. Many students in the minor are frustrated with the system and thinking in dualistic terms, but by offering strategies to connect these ideas, they begin to relax into their practice and things start flowing again.AG

The workshop highlighted interesting contradictions and tensions. We’re working with living organisms, which are uncontrollable and act as their own agents. As artists and designers, we have to step back and be humble about our influence on them, and let them do their thing. At the same time, we create highly controlled environments to understand something far more complex than we can perceive. There’s also the contrast between the collective learning taking place in the garden of Gerrit Rietveld Academie for instance—where knowledge is passed down across generations and seasons—and the more sterile, though not perfectly sterile, lab environment. Another tension is the pressure students face to meet deadlines and pass exams, which contrasts with the slower, more organic process of working with living materials. These different tempos often don’t align.SE

I see a similar tension in education. Some programs emphasize a conceptual approach, so students focus on the look and feel of a material without considering its ingredients or properties. In other programs, there’s more focus on the end product, and students treat material development as just a step toward that result. This can be frustrating, especially with living materials, where growth takes time and often doesn’t go right the first time. I try to focus on material research in my programs, making it process-driven rather than result-driven. I encourage students to see each step as part of the learning process and to tell the story of that process. In graduation projects, I’ve seen students working harder than others, making and dyeing materials with bacteria, only to be criticized for the end result, which is rarely under their control. When working with living organisms, you must shift your focus to the process and accept that you can’t control everything.AG

It’s fascinating. I am thinking about the experience of students entering any type of workshop really—whether it’s glass, printmaking, bookbinding, metal, or ceramics. Sometimes students enter these workshops or lab spaces with a lot of stress. Navigating that stress in the lab can be tricky, I assume. Many educators in more production-based spaces face a mismatch in expectations among themselves, the students, and the tutors—who are often far removed from the hands-on experience but who assess the work. Students often have their own prefabricated expectations, and it’s frustrating when the process doesn’t align with those. But it can also be immensely rewarding when you allow the process to teach you something, letting things emerge and evolve. When it comes to biomaterials, this is even more pronounced, as you can’t predict the outcome and the timeline can be long—sometimes leading to no results at all, or results that are unexpected or not what you wanted.SE

I always hope that students can have the time to sort of “meet” a material or process. For example, I have students working on making fabrics from pine needles—a process that you won't do right the first time. It requires several attempts to understand certain details. You need at least three or four turns to understand the cooking time, but they're often not allowing themselves this space. They’re too focused on the end product and don’t allow themselves the time to explore the process, which only leads to frustration. I can’t solve this for them and it’s hard to shift their mindset, as they’re used to immediate results. It’s like working with wood or clay—you can’t just jump in and expect success right away. We’re so accustomed to instant results that we forget material exploration takes time. Working with living materials forces you to take that time because it's not bending to your temporality. They can’t rush the process.

AG

Right, I’ve been thinking about how specific pedagogies evolve in different material contexts. Teaching methods can be closely tied to the materials and equipment we work with. One thing I found inspiring, and plan to incorporate into my own teaching, is the practice of vocalizing what you're doing. If I remember correctly, this approach stems from a safety concern, but I’d love for you to explain it further. How did you come across this idea, or is it something you developed? How do you practice vocalization in the lab?

SE

The practice of vocalizing what you're doing became important when my colleague Loes Bogers and I had interns, who were all following their individual processes. It helped them understand why a protocol is crucial. A protocol involves going through all the steps and risks before working with a living organism, ensuring safety. Speaking out loud helps them think through their actions and ensures they understand the risks, like working with fire or gas. It’s also a way to confirm they've grasped the instructions and fosters learning from each other. Instead of me repeating corrections, students hear the same information multiple times. Additionally, because we often work with hazardous materials, vocalizing what you're doing helps ensure everyone is aware and prepared for any risks, which promotes better collaboration. We are usually working together in the lab. That's why it’s important that every movement is conscious. If you're not telling somebody what you're doing, they won’t be prepared if something happens. So it's also a way of making sure that everybody is collaborating well, and knows and pays attention to what is happening.AG

Márk and I have been reflecting on the dichotomy between thinking and making. Everyone within the academy seems to agree that there should be no differentiation between material production, the making, and the conceptualization and reflection of that process, but there are few tools or formats to support that constant dialogue. We bridged these modalities by inviting Giulia to introduce texts, but the reading still felt somewhat separate. I wonder if the vocalization exercise could be applied to other forms of making—not just for safety, but as an attempt to articulate something embodied and make it accessible to others. Sometimes it seems there is a resistance to explaining a process, because it might demystify the artistic process. However, just describing what you're doing can lead to new insights, even if no one else is listening. There’s something valuable in making the effort to explicate your process, as it creates a possibility for knowledge to become shareable.MR

This reminds me of a technique called "pointing and calling," which originates from Japanese railway safety practices. It involves pointing and verbally calling out each step of the maintenance process to engage multiple senses and ensure heightened attention to detail in the moment.SE

Yes, this exercise really shifts attention. Even though I know what the students will say, my focus as an educator also remains intense because they’re all vocalizing it. If they weren't, I'd likely zone out after the second student takes their turn, especially if I’m tired. This shows how much the vocalization helps keep everyone engaged, including myself, and I think it helps the students stay more involved in the process too.AG

The way I experienced it, the exercise also gave students a sense of agency, by literally giving them a voice. Being given a voice can also be intimidating, with—as Mathild put it—“the authority of science in the room.” However, the ritual helped foster a sense of community, everyone was in it together. It also made me think about the collective aspect of working with biomaterials, not just interspecies relationships, but human forms of collectivity that evolve too. The act of carrying the box back to the design department with the micro-organisms in it highlighted the shared responsibility, even within a sometimes fragmented institutional structure. It created a new level of communication between us, though managing the care of the organisms was challenging once you left, Sam, especially with our often diverging and ruptured schedules.MR

It's interesting because the vocalization exercise not only gives voice to the participants but also to the materials. When working with living organisms, it's difficult to summon their agency—how do we make that agency present in collective spaces? It's like talking to plants or materials—there's something mediative in that act. It's about connecting the human and non-human worlds, giving a name and a voice to materials and processes. Normally, in workshops with materials like wood or metal, there's no talk like this, no mediation. This exercise, however, brings that interaction into focus, and it changes the relationship. I think that this approach, where you literally "talk" to the materials, shifts the experience. It creates an environment where the materials are seen as participants, not just objects to be manipulated. This vocalization brings more awareness and respect to the material's agency and helps foster a deeper, more collaborative process.AG

I am still thinking about students working with living materials and how they face challenges. It might be helpful to offer them advice on how to deal with the pressure of deadlines, especially when they’re passionate about working with these materials but face resistance or a lack of support from their departments. They might feel pressured to deliver specific outcomes. Do you have any thoughts on how to navigate this situation, or have inventive ways to approach this kind of friction?SE

They could focus on the process and ask themselves: Is there a way within my discipline to present the process itself as part of the outcome? For example, can you present steps or several materializations of the research, or develop a toolkit? In material research, we often start with an idea for an application, then unpack the functionalities and properties needed. The research becomes more about showing the development of those properties than achieving the final application, since time is limited. It’s about breaking down and valorizing parts of the process. Additionally, engaging in material research connects you to a community of practitioners and researchers. It’s about contributing to a discourse rather than simply producing products. Being able to formulate this shift of perspective, could shift the way you're assessed. Thinking through the process, through trial and error, is valuable. These small steps are often discarded or placed in a process book. But they can be seen as part of a conscious thinking process. When organized, like in a morphological chart, they become valuable in themselves, showing the development of your work.AG

Was there anything surprising to you when hosting the workshop at Gerrit Rietveld Academie?SE

What I really liked was taking the time to read the text together. We often give students reading assignments but don't take the time to read aloud. Speaking out loud what you're reading really changed how I engaged with the text. I had done this before when I was studying, but had forgotten its impact. After the workshop, I told Ista we need to bring this method back, and she agreed.AG

After the workshop, we were sitting with Mathild, and they also mentioned the moment we read together. Not everyone knew each other, but something was created in that space—a sense of collectivity and knowledge exchange, and personal stories being shared. It made me reflect on the workshop format, this short-term encounter of people. It's not just about outcomes, prototypes, or products, but also about other forms of knowledge production and the community that forms around specific skills, materials, and methodologies. It’s interesting, especially in relation to the subject of mycelium and networked organisms, and how we conceptualize and relate to them.SE

I think it’s similar to speaking out loud what you’re doing—it keeps you present. When everyone reads a paragraph aloud, you hear your own voice, and that makes it easier to share or tell something. It’s about creating a sense of safety, and that’s what I try to do in the lab space, make sure students feel safe in a lab space.AG

There was this first moment during the introduction in the morning, in the garden. We asked students to introduce themselves and say a bit about what they expect and what they found interesting about this workshop. Someone excitedly shouted, “I love mushrooms!” Mathild said later on that it was not just mushrooms that were produced that day, but much more. I thought it was very beautiful.SE