Conference Introduction by Geert Lovink and Lecture by Joana Moll

report by Jordi Viader Guerrero

Opening by Geert Lovink

The In-Between Media Conference opened up with remarks from internet critic and INC founder, Geert Lovink. After three years without a full INC conference (the prior being MoneyLab in November 2019) Geert was notably happy of being able to gather with a large number of people in the same room. This fact was not to be underlooked, as this very conference was financed by a grant written in the midst and as a consequence of the Covid pandemic and the anxieties around public gatherings it generated. Furthermore, this was also the first full-scale conference organized after a generational renewal at the Institute of Network Cultures. In a way, this conference symbolized an ending, that of the pandemic and the traumas of heavily mediated social interactions, and a beginning, of a new team and goals at INC.

Geert Lovink introducing the conference

questionGeert commented on the reasons this event came to being as well as its objectives: After the isolating Covid pandemic, how can we think and act in hybrid terms? How can we bring together people that are not in the same place? These questions have to be tackled through new hybrid practices and tactics for organizing, streaming, and reporting events. The In-Between Media Conference attempts to be an experiment in these practices while creating a forum for sharing expertise on how to use (digital) media tactically. Lovink also commented on how after the Covid pandemic we quickly moved on to another crisis: the war in Ukraine. Finally, he stressed that the different research lines pursued by INC - hybrid events, meme research, tactical media in the war, and experimental (video) publishing - come together under the question concerning the aesthetics and politics of moving images. Or, in other words, questionthe tactical media question: how can we make local and temporal connections using media? How can we make a hybrid combination of connections?

Opening lecture ‘Data Extraction, Materiality, and Agency’ by Joana Moll

These remarks were followed by the conference’s opening lecture: ‘Data Extraction, Materiality, and Agency’ by Catalan researcher and artist Joana Moll. Her lecture focused on the tension between interfaces and internet infrastructure. reflectionThe internet is perhaps the largest infrastructure ever built but, although it is ultimately physical and has very material consequences, it remains largely invisible to users. These can only access the internet through interfaces, to the point that, from their perspective, the internet becomes a synonym of the interface. Ever-prevalent, the interface dictates what we can and cannot do.

In one of those occasions where entrepreneurial naivete somehow possesses an enlightening clarity, Moll quotes Bill Gates: quote'Power in the digital age is about making things easy'. Interfaces smoothen interactions, making them seem obvious or natural: quote'Some years ago we had to connect to the internet, today we have to disconnect from it', Moll stated. The places where interaction is streamlined are also sites of power struggles. This smoothening takes away agency from users and gives economic and informational power to big tech companies. Moll traces this back to the ideology embedded in the business model of these companies; what she calls, following other theorists, Cognitive Capitalism. reflectionThe wealth of technology companies is no longer produced by material goods, but through intangible actions, such as human communication, experience, and cognition, which are later translated into numbers - quantifiable terms that can be translated into electricity.

The business model of the web primarily relies on ad tech, which trades user attention in the same way that stocks are exchanged in financial markets. Ad tech comprises many different services and products such as analytics, content management systems, etc. It is a complex ecosystem whose main goal is to map and target user behavior. The analogy with financial markets is not obvious nor natural, but rather a set of decisions taken to assimilate networked communication to neoliberal markets. Decisions that were taken during the early 2000s after a migration of Wall Street financial workers to Silicon Valley tech companies. In this context, financial workers applied their working logics to newly-born tech startups. As the 2016 study, “Networks of Control ‘’ shows, every time we do something online a collection of other things are happening - every action is registered and analyzed as classifiable behavioral traits in order to target and predict future user actions. User tracking, or the process of collecting any activity done by users on the internet, is possible because of cookies - a tiny piece of software invented in 1994 by Lou Montulli. opinionAccording to Joana Moll, cookies represented a shift from the internet as a place of anonymity to one where everything is potentially recorded. Montulli didn't create cookies for this purpose, but he acknowledged early on their potential to create a massive surveillance state.

User tracking spawned data markets and brokers. reflectionCompanies such as Acxiom and Oracle boast about having data for 700 million people and the ability to sort them under (absurd yet cynical) user profiles such as 'shooting stars' - gen Xers with expendable income, no children, and who are into jogging. These pseudo-sociological analyses claim to use over 3000 different attributes (in the case of Acxiom). Joana underlined how the mere idea of coming up with 3000 different attributes is absurd. Inviting us to reflect on how many distinct attributes we can come up with (100? 200?), she implicitly posed the question on how these analyses fetishize quantification without knowing exactly how and what they're quantifying. Moreover, she played a promotional video from Hotjar, a company that places cookies on websites to track every mouse movement and displaying them with heat maps. Heat maps show which areas the user is interacting more with and, therefore, those where interaction with advertisement can be maximized.

Yet, no matter how much these advertising solutions brag about their accuracy, they deliberately fail to understand the reflexive quality of the interactions between humans and these virtual environments. By understanding action as reactive behavior, they regard interactions with interfaces as a natural given, a necessary relationship, rather than something that has been designed and is contingent to cultural, economic, and political inertias and desires. This probably also works against the commercial interests of these services’ customers: a static analysis wouldn’t take into account that placing a new ad on spots where interaction is concentrated might drastically change how users interact with the website. Moreover, opinionit wouldn't surprise me (the author of this report) that the results visualized in these analyses will probably be painfully obvious. Like many digital visualizations, these strike as a contrived and ineffective way to state the obvious, legitimized by a lack of trust towards non-quantitative forms of thought as well as an avoidance of political and epistemic liability.

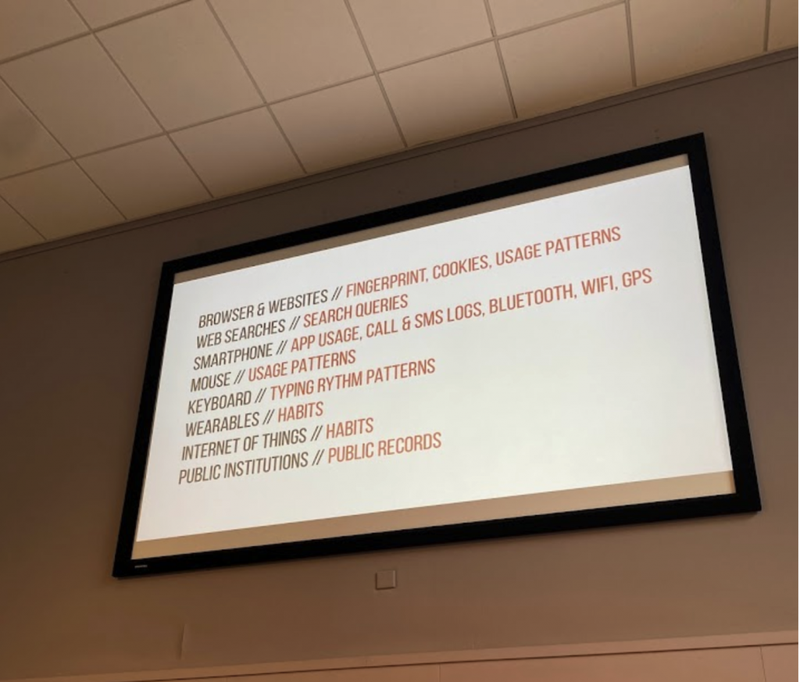

reflectionIn a key slide of her presentation Joana detailed how our everyday use of technology is translated into datafiable interactions: browsing becomes use patterns, web searches into queries, smartphone use into call logs, app usage, and wifi or gps connection points. The machine is not concerned with our personal (metaphysical) identity or our reflexive (intentional) actions, but with very concrete patterns of movement. With this in mind, Joana stated that there is a huge difference between what we share, what our behaviors tell big tech companies, and what the machine thinks about us (how poor or rich we are and ultimately how likely are we to buy again). reflectionAt the end of the day, it really doesn't matter if the analysis is correct or true, what is relevant is that it is productive: that we click/buy again and self-fulfill the predictive prophecy. Even if seemingly understandable at first sight, this data is solely machine-readable, it doesn’t possess any meaning in the same way we think about meaning when interacting with text and images. That’s what Ad Tech analytic services are there for - to provide a resemblance of meaning to aggregated data (and of course charge a premium fee for it). So, it doesn’t really matter if regulation requires tech companies to give users the ability to retrieve “their” data. Even if this requirement is fulfilled, users receive unreadable spreadsheets (millions of interactions sorted out using thousands of attributes, which don’t make sense in isolation but only when aggregated with data from multiple users). The idea that we own our data in the same way that we possess an identity or private property falls flat. It’s a legal fantasy that ultimately benefits the very companies it wants to regulate.

After setting the stage with this articulation of the data political economy, Joana presented her web-based instalation, Carbolytics. Made in collaboration with the Barcelona Supercomputing Center, Carbolytics measures the carbon impact of tracking cookies in the top 1 million websites. The carbon footprint of online advertising is 60 million metric points (the equivalent to 60 million flights between London and New York). This represents 10% of the total energy used by the internet. However, these are all estimates, since there’s no proper agreement on how to calculate the energy consumption of the internet. interesting-practice

Finally, she concluded with a final reflection: we, users, don’t go to websites, the website is coming to us with cookies. Cookies don’t only suck data, but also energy from our computers. Joana closed her talk with a clear political proposal: energy consumption must be included in the privacy rights narrative. reflection

Trends and Aesthetics: The TikTok Limbo

report by Kata Babin

Introduction

Do you find yourself in TikTok limbo? Ever since the video-sharing app popped up in 2016, TikTok has become an omnipresent media whose discursive content is having impacts well beyond the containment of the platform. Following its predecessors Vine and Musical.ly, TikTok prioritises short-format videos, self-referential humour, and user duetting. In the absurdity and vastness of our digital existence, TikTok is the place where niche internet cultures blend with the mainstream through an uninterrupted outpour of microtrends. As addictive as it is endless, the draw of the TikTok algorithm got us scrolling away the days. questionBut how is TikTok becoming more than a pastime distraction? What is the amplifying power of this platform within wider public discourse? That is the question that is explored in the panel ‘Trends, Tactics and Aesthetics: the TikTok Limbo’.

We are seated facing a stage at SPUI25, an open space on the ground floor that is filled with natural light coming from the windows that face into a lively town square. It is cold and misty outside but the space feels bright. There is a podium as well as a table and chairs set up for the round table discussion that will conclude the panel. After a compelling lecture given by Joana Moll which successfully set the tone of the day, the audience seems engaged as we all shift our attention to Dunja Nešović and she introduces the panel she curated: Trends, Tactics and Aesthetics: the TikTok Limbo. mood

Dunja shares that the following panel is a dynamic inquiry into what some consider the youngest, most popular as well as controversial social networking site, TikTok. While many dismiss it as frivolous and mind numbing, others are concerned of its potential as a tool of Chinese state surveillance. It was announced on March 21st that the Dutch government will be banning the use of the app on government officials’ work phones (https://nltimes.nl/2023/03/21/dutch-government-bans-officials-installing-tiktok-work-phone).

TikTok, a short-form video sharing app, represents a paradigm shift in social networking and has become a site of contestation and negotiation. Through exploring user practices, nascent subcultures and the potential of the platform to be appropriated as a tactical medium the panel aims to examine the amplifying power of the platform within wider public discourse.

Tina Kendal, ‘Bored in the (Hybrid) House: TikTok as Ludotopia in a Time of Crisis’

The first speaker on the panel is Tina Kendall, whose work focuses on boredom and the attention economy of networked media. She explains that as we are moving from the pandemic period into an era of permanent crisis TikTok has become the ideal tool for addressing the realities of home confinement, the “pandemic’s bored body problem”. She witnessed the response of creators when due to the pandemic their homes began to feel like prison cells or zoo enclosures. All of a sudden those stuck at home were coping with new realities and strange new temporalities created by the pandemic. reflection

When Tina mentions the trending song that emerged on the app during the early days of confinement #boredinthehouse (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YBsPE6yHH9c), the audience laughs in recognition. Trends such as Bored in the House, where creators lip sync along to the Curtis Roach song, gave us a glimpse into the ways the confinement would inspire users to share in and combat a collective boredom using TikTok. moodinteresting-practice

User tactics were appropriated back into platform strategies and further reinforced tiktok as a machine for converting home confinement into the joys of ambient play. Tina shares that something as simple as choosing more interesting backgrounds for zoom calls was a tactic for this conversion of confinement into ambient play. While an isolated home took on a series of new residences, while it began to symbolise a restricting enclosure, the feeling of being observed (on zoom) and entrapped, the act of staying home and the home itself began to represent the performance of our civic duty, protecting ourselves and others. interesting-practice

Tina proposes that these tactics reinvented the home as ludotopia: inhabitable, multimedial and totally open to public view. opinion TikTok enabled the home to become a meta apparatus for fun and games. The app performs an important kind of work for mass boredom, the TikTok mediated pandemic home.

She explains that the hashtags she looked at were #boredinthehouse and #boredvibes which contained both performative and stunt TikToks, both showed creators embracing the pleasures of full body participation encouraged by TikTok’s memetic structures.

Performative TikToks contained creators lip syncing and performing dances which were all performing an important psychological function. These TikToks are essentially a performance of entrapment and are mirroring our shared experience of being stuck at home. The tone of these TikToks are playful, energetic and joyful. They are participatory, connective and create a co-presence between both creators and users. A social solidarity within the context of lockdown. It is with ambient play that this co-presence and intimacy are accessed, by moving beyond entrapment they create links with other creators who are also bored in their home. reflection

Tina then moves on to describe stunt TikToks. These TikToks focus on the space of them home itself as the object of ambient play. They activate ambient play as a means of working on the sensory or affective texture of the home. Examples of these would be a extreme slip and slide courses, dirt bikes through the home or playing sports inside. Watching stunt TikToks have the ability to provide a certain kind of pleasure and a fantasy of escape. They reimagine the home as a playground rather than a prison. This is tactical as creators invented ways to produce the home as a joyful shared zone for creative invention. It opened up an awareness of the creative affordances that have previously been overlooked within the home.

Tina references the work of Ian Bogost who wrote the book Play Anything: The Pleasure of Limits, the Uses of Boredom, and the Secret of Games (https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/09/how-to-use-fun-to-find-meaning-in-life/499805/). She quotes him, saying: quote"Fun comes from the attention and care you bring to something, even stupid, seemingly boring activities. It’s a foolish attention, even. An infatuation." interesting-practice

Tina discovered that TikTok provides a set of tools to help produce powerful feelings of co-presence as well as enliven the rhythm and textures of the home. It introduces the home as a potentially endless party zone that yields to the whims of its inhabitants. reflection

At the start of the pandemic TikTok created the #HappyAtHome campaign in an effort to contribute to the global stay at home effort (https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-us/staying-happyathome-with-tiktok) which incorporated livestream elements. interesting-practice The platform benefited immensely from the global need to stay home and combat boredom. It relies on the bored body as a basic requirement of its model as well as domesticity as a condition of being bored in the house. The condition of being bored in the house can also be recognized as chronic to digital culture. As a result reflectionplatforms like TikTok embody both the potential for tactical reinvention of the home and confinement as well as digital capitalism and control.

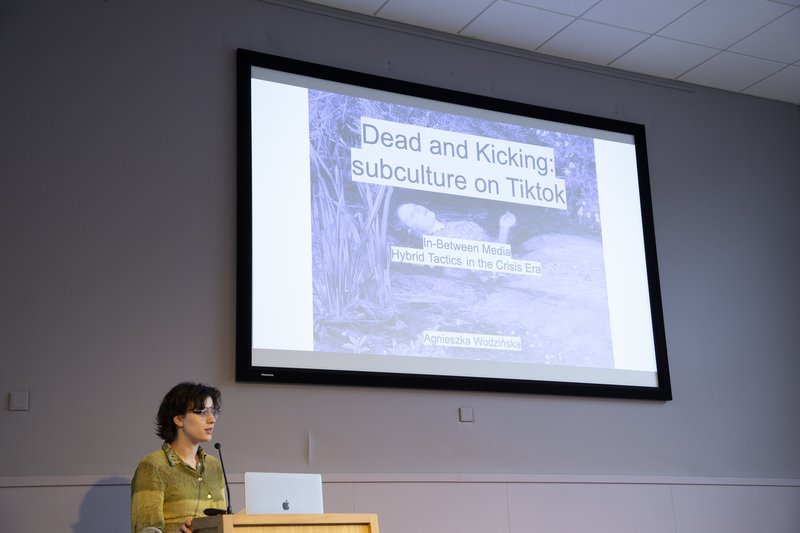

Agnieszka Wodzińska, ‘Dead and Kicking: TikTok and Subculture’

Next on the panel is art historian Agnieszka Wodzińska. She is interested in aesthetics and the digital space, how aesthetics on social media platforms can become political and the limits of it.

She begins by sharing the definition of a subculture in the context of her research, “a group of users that both possess and express a certain interest and ideas that in some way are not mainstream or are counter hegemonic.” She gives the example of the trend #cottagecore which elicits nods and chuckles from the audience. interesting-practicemood The cottagecore trend with its slow living, back to the earth aesthetic, possesses a lot of potential for quite obvious anti-capitalism. On the surface it rejects toxic productivity and attempts to rethink our relationship to labour. It encourages those witnessing it to slow down, reconsider and take up non-digital hobbies. It is a reframing of domestic labour and illustrates a way to function outside of the capitalist and patriarchal structure. Although it began as a seemingly inclusive and progressive space there is a very clear overlap with the tradwife movement which has ties to right wing extremist spaces online (https://www.vice.com/en/article/3ak8p8/online-rise-of-trad-ideology). interesting-practice This rethinking of domestic labour then becomes the idea that unpaid, unrecognized domestic labour should be expected from women. These very different sets of beliefs fall under an eerily similar aesthetic which creates a dangerous ambiguity in aesthetics online. reflection

Agnieszka then introduces her main topic for the presentation: the trend #corecore, this is followed by laughs of recognition from the audience. quoteTo define corecore she quotes Kieran Press-Reynolds “an anti trend, loosely defined as similar and disparate visual and audio clips meant to evoke some form of emotion.” (https://www.vice.com/en/article/wxnmeq/corecore-tiktok-trend-explained)

We are shown a TikTok video from the user @nichelovercore, a compilation of sentimental video clips, there are giggles from the audience when the TikTok ends with the apps familiar chiming sound. interesting-practice Agnieszka explains that corecore is an anti-trend, the name itself evokes a sense of self awareness and meta criticism. The videos explore the idea of compilation with overlapping clips; it evokes feelings of chaos. Clips come from already existing media, television ads, films, interviews, mass media and existing TikToks. They decontextualize and recontextualize content that creates a sense of disastisfaction with life within capitalism, they exist as critics of the platform in which the content exists. These videos have the potential for activating users that realize the elements of social media that are no longer working for them.

Agnieszka points out that corecore risks evoking a sense of self-pity for users, not activating them in a meaningful way. The videos highlight struggles and can lead to a collective sense of dissatisfaction. The message can be interpreted as romanticizing loneliness, saying “loneliness is beautiful.” It can create a de-political sense of individual struggle, focusing on the self without recognizing the issues at play. What Agnieszka did not expect while doing her research is how easily someone consuming corecore content can be shown alt-right related content by the algorithm. By making a new TikTok account and watching corecore videos she discovered that videos of or from controversial figures like Joe Rogan and Jordan Peterson would appear on her FYP, videos focusing on an obsessive self improvement that do not acknowledge the systemic issues at play. opinion

One thing she discovered is that while corecore began as a sort of hopeless nihilism, now many videos tagged #corecore share the tags #hopetok and #philosophytok. She says that many subcultures exist as bubbles in a venn diagram and overlap in interesting ways. #hopetok videos contain more hope on the future of social media and societal relations and Agnieszka predicts that it may be a new direction we will be going with this type of discourse. reflection

Agnieszka then explains that corecore videos are a form of sticky media, users want to come back to it and rewatch because they can’t be sure they caught everything. They think that there might be something in the compilation that will reveal itself to you if you just keep scrolling or replaying the video. She then compares the trend to zombie formalism (a term coined by Walter Robinson, https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/zombie-art-formalism), that it is reviving ideas of modernism. It is possible that it captures soulless and performative motions, a simulacrum of originality that is desperate for a sense of development or progress. She says that we are so desperate for a sense of progress that we create false or artificial milestones, such as the first painting made from paint placed in a fire extinguisher.

She asks, questionis corecore going through the motions of aesthetical resistance without actually embodying it and making it its core? She explains that online subcultures are like zombie beings, they have skeletons that are recognizable to us, that share ideas between users and aesthetic interests. However, the meat of this body is from what she’s seen is kind of rotting and mutating to a point where it is hard to trance. Trends that are usually static and easy to trace have become more fluid and tricky with social media. This aesthetic ambiguity of online subculture, if we take time to think about it and its implication it could push is a direction of actual resistance and tacticality. quote“Corecore has the potential to be very activating for users.”

Agnieszka concludes her presentation with the question: “Is corecore something that can break out of this zombification or will it just continue existing and just be animated by the sheer speed of social media? Will the platform absorb this public critique or will there be away for users to break out of this very unusual cycle?” quotequestion

Jordi Viader Guerrero, ‘Infinite Scroll as a Symbolic Form’

Jordi’s presentation starts with a classic technological mishap followed by the audience’s knowing chuckles. The screen of his presentation is purple and it shouldn’t be. Once that has been sorted out he introduces himself. mood

Jordi is a media researcher and PhD candidate at TU Delft. His research explores the intersection between philosophy, media, design, political theory, and technology. His project began during what he refers to as the darkest times of COVID. Early 2021. His goal was the abandonment of a specific way of doing theory and the issue of meaning. His project, called Infinite Scroller “proposes you, the reader/scroller, a general theory of scrolling —as much aesthetic, epistemological, and political—, while also encouraging you to experience theory as an overwhelming, multi-layered, and immanent event composed of networked text, images, and sounds to be seen, listened, touched, danced; that is, scrolled.” He explains that he started by creating fragmented video essays about TikTok on TikTok (@infinitescroller). The aim was to make theory differently, to “scroll through theory.” interesting-practice

So, why scrolling? Jordi’s interest in it starts with the fact that scrolling is a practice that can be datafied. It is also a place of amazement. We spend a lot of our time during the day just sitting and scrolling. This is a motion that technological devices have created. He wants to see scrolling in a theoretical way, this perspective as a symbolic form. The visual perspective of scrolling has a deeper philosophical meaning. This is because perspectives structure the way we experience the world. So the question becomes: question“how does scrolling come to structure the way we experience the world?”

Jordi says he abandoned the question of the symbolic and started to think about perhaps not asking what scrolling means to us but look at scrolling as something that we actually do. Something that actually exists in the world and happens. Scrolling is a material practice and so he wanted to take videos of himself actually scrolling. He opted to film himself at home while bored, scrolling to make his TikToks.

He says scrolling is a way to interface through these very complex infrastructures and it simplifies it to the user. It is a way to access information. Not just the access point but also the end. It is something we WANT to do, not for capturing or communication but for the sake of it. How can we complexify scrolling? The idea then became to denaturalize this reflexive physical loop of scrolling to make it opaque. To make the project difficult and complex.

Referencing Agnieszka Wodzińska’s earlier presentation, Jordi says he was completely illuminated by corecore and its criticisms. opinionHe sees scrolling as a collective practice, not individual. It connects us both to the app and all this other existing infrastructure. There is no power of negotiation because these complex systems are being simplified. We are all made to come together and collectively participate in these systems.

Jordi asks, question“why does scrolling have this power over us, why are we succumbing constantly into it?” Scrolling as a place for pleasure production. The information is not just for consumption but for pleasure production. He wanted to abandon theory, see scrolling as engaging in practices of pleasure. He admits that he did both TikTok and theory wrong in his approach to this project, he did not have a proper theoretical framework and the TikToks he made were very weird, there was no coherent line through it. The audience laughs as he follows this thought with a playful request to like and subscribe to his TikTok channel @infinitescroller. Now that he knows about corecore he says, his videos aren’t as weird as he previously thought. He explains that he had attempted to hijack or infiltrate trends to see if he could gain viewers for his videos but he failed and did not become a popular TikTok creator during the pandemic. His most popular video was located at a skate park so there is a good chance the viewers were skaters and that is why it gained views.

Jordi says: quote“we are scrolling machines, we are stuck there. Now what? What do we do with ourselves now that we’re trapped in this scrolling feedback loop?” He wants us to think of our relationship with these devices in different ways. To think of scrolling as a space of production. The audience laughs when he adds that that perhaps sounds capitalist in a way. He sees emancipation, joy, desire, emancipatory and positive passions coming from scrolling, basically Live Laugh Love. He concludes, quote“I’m too young to be too pessimistic.”

Discussion, moderated by Dunja Nešović

The round table starts off with some technical problems with the mics, which again elicits knowing chuckles from the audience. mood Dunja, Tina, Jordi and Agnieszka sit around a table facing the audience. Dunja wants to explore the potential for tacticality with TikTok and the notion of dual tacticality. She notes how boredom is appropriated and exploited by TikTok and there is a need from the users to employ media tactics. Platform intervention that are steering ideologies and dual tactics that generate in the platform environment. She asks question“how are users are being invited to employ platforms to convey certain political or social action while also having to fight this platform giant that has its own interests in the matter?”

Tina is the first to speak, she says that boredom is a bi-political issue, boredom is activating the scroll as a mindless gesture. She says that she likes the way Jordi approached scrolling as an affective source of pleasure. During the pandemic she says she was involved with a young creatives program which pivoted to a co-creative project getting young creators to use TikTok to document what boredom felt like during confinement. They were encouraged to use TikTok in a way that was antithetical to the way it’s meant to be used. This included tactics such as setting their videos to private to be used as a diary space, any use that was different from what we are used to seeing. quote“They were trying to break the typical link between boredom being only this automated gesture that you shouldn’t think about anyway.”

moodJordi says he is interested in the topic of boredom and platforms taking advantage of boredom. He bring up the classic internet insult of telling someone to go outside and touch grass which elicits laughter from the audience. He doesn’t think that TikToks are just boredom killers, they have the potential to be so much more. Looking back on the history of cinema, it used to be considered a waste of time, going to the movies to kill boredom. Now we regard it as a good and productive thing to do, it doesn’t have the same negative implications. We can “modify the parameters of what is expected of us to do with these platforms” by resignifying, reinterpreting and rethinking the gestures that are expected. reflection

questionDunja asks what are the different sites of subversion, reconceptualization of the platform, things that might not change the platform so much but resignifying, recontextualizing what you’re already doing? What are the possibilities for the users to change their attitude towards those types of appropriations instituted by the platform? Users perceive platform powers as marginal, tolerated rather than defeatist, a kind of acceptance that “we’re trapped now in this environment.” We are fighting against platform power, tension between the two ideological struggles between corecore being left-wing, these ideologies mutating into right-wing ideologies facilitated by the platform, fighting the algorithm as an ideological battle. reflection

Agnieszka responds that users are attempting to navigate this struggle. The trick is to stay vigilant and think of the wider implications of the decontextualized snippets. The platform intends for us to view them as they all fit together but it is important to think of them individually. The ambiguity makes it interesting but also dangerous. Tina adds that the platform doesn’t recognize the ideological stance. question“Is it the videos or the algorithm that dictate the ideological trend?” opinionAgnieszka answers that it is unclear what role the algorithm plays in the creation of subcultures. She says corecore originally, this being only a few months ago (the audience laughs at the newness of the trend) was anti-capitalist. It then exploded into other hashtag subcultures. The fact that there is no cohesiveness makes it interesting and the platform does not want transparency of their algorithm.

Dunja then raises the question of affordances. question“Are there certain ideas on what types of affordances on TikTok are relevant for being used in different types of tactical ways as well?”

Jordi responds that it is more interesting to create our own ecosystems to use the platform in specific ways. To create our own affordances instead of letting TikTok dictate the way we use it. We can do this by creating workshops, groups of students, friends, reading groups. By having a political purpose and using the media in different ways. The algorithm affords the creation of subcultures, we often end up in very niche sections of TikTok which would very clearly not be what TikTok wants as an image of their own platform. He says it’s as if you end up in this weird dark alleyway of the city and jokingly admits that he may be a defendant of filter bubbles. Jordi doesn’t think that the algorithm has full control of determining these subcultures and the different ways they flourish. opinion

Dunja asks for a reflection on the tension between the visual field on TikTok and invisible, what structures our experience on the platform. The visual field is the main arena of possibility, TikTok is a visual platform or medium. She asks question“What is the relationship between visual medium and user tactics?”

Agnieszka says that the visual language of trends like #nichetok, #corecore and #philosophytok makes invisible TikTok visible. There is a visual business. She says that “users reflect more consciously on the more embodied, practice and experience of scrolling, consuming and interacting.”opinion There is even more to be said about the comment section, it provides the potential for some sort of exchange which is often meaningless and surface level but maybe not. It is a “new sort of structure for interaction that is more referential to other platforms and other ways of engaging” there may even be ways to get off the platform together somehow and revisit it later.

Tina remarks that TikToks don’t actually make boredom visible at all, they instead show users what to do when bored. This is the paradox of digital formats. It is rendering boredom invisible, hiding it all together. reflection

Jordi responds with questions of his own: question“How do we act tactically with the visual?” He is more interested in all of the practices around the visual, both production and consumption. question“What are we doing with these practices, how can we make these practices tactical or political rather than something of the world? Is art production a way of political engagement in the world or is it something outside the world?” It is more about the practices around it, changing how we see it. Reconceptualizing the practices.

And with that the floor opens to audience questions. Audience member Florian Cramer states that corecore has gone alt-right, as part of the manosphere it is where men scream their anguish. This is not just due to the algorithm, he wonders is this the new 4chan? Similar ephemeriality and dadaist form that becomes the alt-right medium. Agnieszka says that it is interesting to consider corecore as something that is already gone. She still has a sense of hopefulness within her that we haven’t lost it completely to the far right. Perhaps it is something that is mutating and transforming/overlaping into this niche side of titkok that has a hope angle, like #philosophytok or #hopetok, which have little no association with conservation politics. She leaves the possibility open, saying, “let’s see.” reflection

Geert Lovink is the next audience member to contribute. He sees infinite scroll as “a regressive phenomenon, an end of the social of social media, end of community.” He says it is a subliminal activity, pleasure of braindead activity. It has gone full circle, only one step away from full automation and is another form of zapping of the television channels. “The early internet was presented as a critique of this passivitiy, you can participate, create, take over the media. Do you think scrolling has this almost automated nature?” opinion

Jordi responds that quote“scrolling in and of itself will not get us anywhere.” Scrolling can be described as a regressive gesture, a machinization of our movements and therefore dangerous politically. The novelty of it comes precisely out of when you do something different. opinion“All of our actions are mediated by technical systems, there is no difference between scrolling and joining a political party” like all the actions we do collectively in the world together. We must convert it into something that is more than machinic and make other actions around it. Not letting the scrolling define itself for us. There is a revolutionary potential of collage, while the collage had been co-opted by corporations for advertisements, scrolling can be considered like passive surfing channel consumption. The key is to use the gestures and affordances differently.

Geert adds that there is a subconscious production of power. Jordi agrees that the embedded automatism is very difficult to fight against, and jokingly says we should make our own psyops. Dunja responds that reconceptualization of scrolling is not subliminal, it is very conscious.

Finally, Tina concludes the panel by adding that people are incredibly conscious of their digital consumption, especially during the pandemic. Symbolically the infinite scroll was very comforting in the context of the pandemic. It was almost a meditative act, there is value in thinking about those sorts of gestures as providing comfort as well as acknowledging how it can be deeply problematic.

Practices of Streaming Resistance

Outcomes

[Here we can write a few sentences on the output format]

General Information 🎁

Program Segments

copy & paste according to the amount of sections of the program] **–>

As we are sitting at Spui25’s brightly lit room, preparing to dwell into Practices of Streaming Resistance.*** ***

Following a brief introduction, we welcome on stage Karl and Margarita from The Hmm and Hackers & Designers to talk about Thresholds of Access.

The second presenter, Cade Diehm walks on stage. His presentation on Digital Infrustructure Resilience and Weaponized Design starts in a fun and joking manner, establishing a welcoming atmosphere, a beautiful break from the “doomy feeling” that is so present in academia.

Weirdness does not stop here. As Roman Dziadkiewicz walks upon the stage. He is here to represent UKRAiNATV and talk about Stream Art, Hybrid togetherness.

Roman’s presentation was followed by a round table featuring the speakers, moderated by Margarita Osipian.

- 1. Margarita Osipian and Karl Moubarak - Thresholds of Access, a conversation between The Hmm and Hackers & Designers

- 2. Cade Diehm - Digital Infrastructure Resilience and Weaponized Design

- 3. Roman Dziadkiewicz - UKRAiNATV, or: Introduction to Stream Art, Hybrid Togetherness and Virtual Politics

- 4. Round table with Cade Diehm, Roman Dziadkiewicz, and Karl Moubarak, moderated by Margarita Osipian

Red Thread 🤔

Live Streaming can bring people together and offer support in the time of crisis, when other forms of connection may be impossible, be it COVID or war. DIY live streaming can be an effective method of political resistance. Although there are many tensions present: between the political agency of self hosting and the technical restrictions, open source and accessibility, urgency and quality. Experimenting instead of just theorizing, and having fun with streaming, could antagonize the doomy feeling of our day-to-day reality. red thread

Repository 🔗

https://github.com/hackersanddesigners/the-hmm-livestream

bodybuilding.hackersanddesigners.nl

https://docs.mux.com/guides/video/start-live-streaming

https://newdesigncongress.org/en/pub/the-para-real-manifesto

https://ukrainatv.streamart.studio/knowledge/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UMBxESl38o0&t=55s

https://thehmm.nl/?s=archive

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gamergate_(harassment_campaign)#:~:text=Gamergate%20or%20GamerGate%20(GG)%20was,primarily%20in%202014%20and%202015.

https://nieuweinstituut.nl/en

https://incels.wiki/w/Pinkpill

https://incels.wiki/w/Redpill

Event page:

Instagram:

Livestream recording:

Chat:

Transcript:

Blog-post:

Pictures / screenshots:

Bios:

From Tactics to Strategies

We start the last session of the first day as a dive into the more complicated political questions: the how to reclaim the internet, organize ourselves collectively in this undertaking. Before giving the mikes to our speakers, Tommaso argues the event to be part of a tentative in building alternative tactics, and raises the preliminary condition for its success: gathering tactical knowledge about platforms, bringing it together. This is the only way to “move from tactics to strategies”, from the user to the collective misappropriation.

The red thread of this session is one of the responsibilization, from the little practices and misuses of platforms to the bigger strategies to adopt in the face of powerful technological actors. We are too often ready, though we do not admit yet even recognize it, to sacrifice technological independence by using Big Tech, hosting on its “cloud” and naibely archiving on its platforms. If we need to go from tactics to strategies, we need to start putting our own practices as activists into question, learn from past experiences and engage in new ways with our current technological context.

1. LURK: Jenga Computing and Precipice Workflow, Aymeric Mansoux

Aymeric Mansoux first comes to the stage, with a lot of technical preoccupations as part of his “half-improvised” presentation. “Jenga computing and precipice workflow” is the title of his intervention, announcing to the audience the complicated situation in which alternative infrastructure tries to survive. How to bring about sustainable mode of workflows, to maintain these autonomous technical infrastructures that we cherish and praise in theory, yet hardly work on actually sustaining, yet even deploy, in practice?reflection

Aymeric makes a disclaimer from the start: he will mention infrastructure a lot (that is, servers) and how to deal with them. He will only talk about the context of northern-western Europe, starting from his own experiences with “Lurk” (https://lurk.org), which he started with Alex McLean in 2014 as an “independent e-mail and web discussion platform for computational culture”. Lurk is “an infrastructure which facilitates and archives discussion”, from mailing list hosting to streaming, chat, access to the Fediverse via Mastodont, …

Through the history of Lurk, Aymeric aims to expose both a “hopeful?” techno-cultural perspective (or at least possibilities), and a “bleak?” socio-economic context. The idea for Aymeric, it seems, is to shake us in regards to the too-often neglected aspects of alternative infrastructures – of the economic condition in which they try to survive, and of the actual cultural practices, which do not necessarily tie back to our discourses about them.

“By 2014, everyone has given up on critical, alternative infrastructure”, he recalls. “People moved to the ‘user condition’, about what we can do with our own data, …”. At the same time, some were pleading to “bring back mailing lists, to bring back discussions to system [they] can own”, and then archive.

“By 2017-2018, we were getting tired [in the alternative infrastructure ecosystem], fed up with everything”. Aymeric talks about “admin burnout”, which is a notion that I, and probably many other digital-workers in the room, can relate a lot to. Yet parallel to this exhaustion, was a collective excitement as to alternatives such as Mastodont, the Fediverse, which revived the discussion at the time.reflection

During the Covid years, Lurk had time to consolidate and deploy things. Aymeric tells us about this “eurika” moment of his, recently: “what we are going on is not a repeat of 10-15 years ago!”. This is the “Musk-Twitter” moment, which can be described as such: “Lurk is composed of people not so much engaging in sharing infrastructure and software, as it is of a community that wants to participate in an infrastructure of healthy, sensical discussion.”quote

2000 people subscribed over 60 mailing lists, a maximum of 666 people on the Mastodont instance, 400 external people using Lurk’s chatrooms. “It is small compared to Twitter, but still significant for us”. However, “a lot of work is needed to not have it collapse”, it is not just “magically working” (this phenomenon of relating to technology like if it was working by magic, seems to summarize well the situation Aymeric wants to decry).opinion

A lot of humour is invoked to partly dispel the weight of responsibilities that comes with Aymeric’s presentation. Community servers becomes a “dinosaur story”: “why did they disappear? they were so powerful!” says Aymeric to a laughing audience. However “there are many obvious reasons as to why they are hard to maintain…”mood

To conclude, Aymeric reminds us of the material complications driven by the socio-economic context we are living in, starting with the price of the rent that almost doubled: “this has an impact on what you can do, developp”. As he explains, “we started Lurk because we were old and priviledged enough to do it as a side-job”. Now, “Lurk is constantly on the precipice of the socio-economic situation” (starting with inflation). How can we run infrastructure sustainably in our context? Having these kinds of side-jobs is increasingly difficult…reflection

For Lurk’s free hosting services, they need to find at least 400 euros per month, just to run and maintain it. “How do we invite people to a nightmare of maintaining infrastructure without getting paid?”. Aymeric talks about the frustration in the work done by people involved in alternative servers. A work full of struggles. We need to “go beyond an academic understanding of infrastructure”, and stop the exploitation of people maintaining technology. “The only way around it is the individual contribution of the person”, he believes.opinion

With a workflow constantly on the brink of the precipice, to having the infrastructure collapse, “everybody is an entrepreneur, nobody is safe”, as he explains by displaying the book of the same title on-screen. “There is not much talk and writing on the precarity of the cultural sector, the ‘entreprecariat’”. For him, beyond the easier and better-known questions of cultural, political and ecological issues of infrastructure, we need to start paying more attention to its actual technical aspects, in terms of maintenance.opinion

2. How-to.computer: A Self-Hosting Guide, Lukas Engelhardt

We move on to Lukas Engelhardt’s “how-to.computer: a self-hosting guide” presentation, which he disclaims as “some naïve optimism to counterbalance the previous talk”. Lukas is a graphic designer that stoped using centralized servers in his own workflow and engages with their very materiality. “How doe they look, feel? How are they maintained, by who?”, he starts by asking.

Through his “manual”, Lukas wants to make people build their own servers, in order to “stop using dropbox”. Practice is at focus here: “We criticize Big Tech, which is important, but then we use Microsoft Teams, Google Docs, gmail … it is difficult to make the switch”, even for hackers, even for cultural institutions aware of the issues of using Big Tech technologies.opinion

So it is all too often tempting to go on “the cloud”. quote“The cloud is only present, dominates the internet, and people don’t know what to do about it. How to drop it back to the ground? The cloud is out of reach, or seemingly unreachable”. Lukas has just played a 2 minutes hilarious video of someone shouting at a cloud, trying to make it magically disappear in front of him – repeating frantically and in different tones (in case one of them has more effect on the cloud) “kleee disappear! Kleeee disappear! Kleee disappear!”mood

Facing such an out-of-reach cloud, it indeed seems to us that only a mystical approach of incantations can make it dissolve. This makes me think of people desperately dancing together for the rain to come, except that here, it is shouting alone at a cloud to make it disappear. The cloud, be it atmospheric or as a metaphor of digital servers, does indeed have a mystical resonance with us: a power we desperately try to seize, but that is beyond our actual will.reflection

The cloud is a fuzzy term, explains Lukas: it is “the rest of internet”, out of control for the majority of people. “That is why the term was chosen of course: it is mysterious, unknown by definition”. Yet, quite paradoxically, the cloud “is just someone else’s computer”, as he simplifies through a t-shirt image with that catchy explanation.

When we give data to “the cloud”, we don’t control the terms and conditions of our data – “there is nobody to talk to if something goes wrong” (such as when data disappears). How come it is so seductive to us, then? “People expect things to work immediately, without delays”. This is what Lukas calls the “cloud narrative”: “things should always seem light, easy, and anything that betrays this principle betrays the façade image of a cloud”. From this narrative and its related practices, “we are spoiled, used to have 99,9% constantly smoothly available”.opinion

Can we learn from the squatting movement, when it comes to network activism and spreading the practices? Lukas tries to make a connection between the squatting movement and the hacker culture, historically present in the Netherlands. “‘Cracking’ was used for ‘hacking’”, he recalls. Could we engage digitally in “temporary autonomous zones”? We can also learn from feminist theory: that is, as to “space run from a community that has enough motives to take care of it”. Instead of seeing this caring time as a lost time, we should start seeing it as an essential time for community-making.interesting-practice

Someone in the audience tries to challenge Lucas’ analogy, by asking where is the political in self-hosting, as opposed to claiming an actual space. Lukas admits that the analogy of space does not always hold, as there is not the same direct conflict and competition in digital space as there is in a more physical one, such as a house. For Tommaso, bouncing on this comment, it is actually possible to squat datacenters: “as we do at the INC, to take a very personal experience”. Geert then argues that be it in a physical or digital space, “without self-organization, nothing happens”.

3. The Tactical Misuse of Online Platforms, Nick Briz

As we move on to the third intervention of the session, and as we get emotionally drained by these different displays of our collective disempowerment by Big Tech or the socio-economic situation, nothing could be timelier than Nick Briz’ presentation on “the tactical misuse of online platforms”. Eventhough it must be noted that he appears to us through Microsoft Teams, which makes the audience giggle, especially as he struggles to share his screen.reflectionmood

People tell him to check if “he has all the rights”, Chloe tries to make him an “attendee”, then a “presenter”, … until finally Nick realizes: “ah, it is the ‘share’ button!”. He must not use platforms quite often indeed. Nick is about to tell us how to misuse platforms designed to use us – that is, designed to collect our data, to train algorithm able to predict our behavior and manipulate it accordingly. An attempt in tactics of online privacy, in the context of surveillance capitalism.

As he explains, platforms “don’t need so much data to manipulate us!”. As for Uber, for instance, they just need to extract battery data, “which they exploit to charge higher fees”. This single data extraction allows them to manipulate our behaviors, when we are anxious with low battery on our phones - which they use against us, bypassing our awareness of it.

But his presentation is not about displaying all of these manipulations’ techniques, quite the contrary: it is about counter-manipulating platforms that are based on the manipulation of our behaviors. Because if platforms can manipulate us without our awareness and consent, this might as well apply the other way around? Here comes the crash course.

There is one underestimated, simple way through which to misuse the platforms: the web browser through which we access them. Nick’s website (https://tacticalmisuse.net) contains “a collection of creative & experimental ways of using the browser to engage w/online platforms in a manner that undermines the exploitative algorithms + dark patterns designed by the data barons of surveillance capitalism” - which he encourages to use after his presentation.

At the core of it, explains Nick, is the idea of “not using any interface of platforms in the ways they are designed to” – no button clicks, only the browser’s interface. While platforms like Instagram constrain us to log in, to access an image, for instance, we can simply use the “open link in new tab” option of the browser to subvert the mechanism.

We can also use the “inspect” tool of the browser through right click, usually used to debug, but which can be misused in tactical ends. Through this feature, we can manipulate the code of the website and platform, to go beyond the “blur” screens of surveillance capitalism (Nick de-activates in front of us the <div> element of the Instagram page responsible for blurring the picture, unless you are logged in).

For more experienced tactical misusers, the console tab allows us to inject our own code. Through it, we can remove all the metrics of Twitter, remove Google services from its search results,… scripts are directly available on the website to use, we don’t have to write them ourselves.

It is a nice feeling for the audience to have these very practical, small - though not insignificant - perspectives to tactically misuse Big Tech right now. These “little hacks” are accessible enough to everyone to “mess with, hack, play” the constraining surveillance code of the Silicon Valley’s giants. They go “from simple to proficient hacks”, some that any user can do. mood

In answer to a question from the audience, Nick expresses the responsibility for more competent programmer to pre-make hacks and make them accessible to a less-knowledgeable public, that don’t have the time and energy to learn programming. And finishes with this opening: can we tactically misuse Chat-GPT? As he explains, through this kind of generative AI, “the entry barrier is getting lower and lower” to generate functional code and scripts, that we can just copy-paste for our own tactical ends. quote

4. On Tactical Video Archives, Donatella Della Ratta

We finally arrive at the last session of the day, by Donatella Della Ratta, on tactical video archives. As she plays an amateur video of what seems to be a conference in Syria, in the early 2010s and during the insurrection, we get the feeling that we are getting back to “dark academia.” The speaker in the video explains how “YouTube is a necessary tool to reach international media.” mood

But no, this won’t be a boringly academic presentation to end the day. As the sound of the man’s speech fades, and an ambient music makes its appearance in frantic rhythm, evoking the battlefield and its harshness, Donatella starts her own narration in such a way that, despite being the end of the day, it catches everybody’s attention by surprise.mood

“It is September 2011, a few months before the Arab spring. I am reporting for the creative commons.” While the Syrian regime kills activists, she attempts to get a migrant to Warsaw safely by getting him a visa. Syrians gather “the image evidence”, in the words of Georges Didi-Huberman, “to prove the crimes committed against humanity”.

“I fear for my life, I also fear for the life of these images”, Donatella recalls hearing. In this context, the “social web” was needed for archiving. “War became a mundane activity, routine labor, a source of income” she narrates. Yet, “pixelated, blurry videos of the aftermath of the uprising was no more enough for the international public”. Clips became no more representational but “performative utterances”, communiqués of soldiers in Syria.quote

In one night, all of the many images disappeared from the YouTube platform. This was the end of belief for videographers that “things are going to be out there forerever”. “I was convinced that Youtube was like my memory” Donatella recalls hearing. Yet, what you loose on Youtube, you never get back.

Activists have forgotten or ignored the need of the local copy of files, or to archive their footage on alternative video platforms. Of course, this can be explained by “the urgency of the revolution in the making”. What was left? “Orphan images, with no makers, no sources, …” in the hands of people in Silicon Valley, knowing nothing of Syria.

What do we make of activism today? Is there still a space of possibility for tactical media when it is controlled by tech giants? What has citizen journalism become in the era of TikTok? Visual culture now, according to Donatella, is a special case of vision, an exception to the rule. “At a time in which computation has become hegemonic, how do we build counter-hegemony, when images become hardly visible to the human eye?” question

This intersection between computation and images is of crucial political matter, she argues. We are feeding algorithms with data in how to identify places, faces, … to be reinjected as commodification into algorithm. “All things human automated, now independent from the human eye. Our tactics have to shift in this context: activism has to focus not so much on producing counter-narratives, but rather in targeting the images of computational capitalism.”quote

As image and information flows are by design hidden in computation, what is most powerful: images or codes? Are coders or photographers more needed, in our context? According to Donatella, the Syrian rebels have showed us the importance of codes, beyond images. What we need now is a generation that thinks beyond the ideality of the image, as well as beyond “just an image”. We need to think about the image first and foremost by thinking about non-images, and their increasing roles in conditioning the former.question

Donatella finishes her speech, and the audience contemplates for one minute the consequences of all of these evolutions, as the ambient rhythm in the background fades out. Jordi asks: “After the photographer, who do we have now?”. We should work with coders, replies Donatella, make the effort to collaborate with them, or even code ourselves.

quote“Networked images are operational images: it does not matter if they are true or false, but rather, how they circulate and how sticky they remain.” With these words, the first day of the In-Between Media conference end, leaving the audience with a renewed sense of responsibility, well beyond the Syrian or Ukrainian battlefronts.

Small, Clumsy, and Intimate Devices for Awkward Hybrid Settings

by Senka Milutinović

Wait. questionHow are hybrid settings actually affecting the way we sense others’ presence in public events? questionHow can we bring intimacy when hybrid media interrupt instead of facilitating modes of togetherness? In this three-hour workshop, participants built their own small, clumsy, and intimate devices to hijack the idea of hybridity.

Small Clumsy Intimate Devices for Awkward Hybrid Setting was lead by Chae and Erica, two Exerimental Publishing Masters (XPUB) students from the Piet Zwart Institute. This workshop asked how we can bring back intimacy and modes of togetherness when hybrid media interputs. We started off by dividing roles to read the script of the workshop. Clumsily, we were reading as narrators, announcers, quotes, and facilitators while canonic elevator music was playing in the background. From the quotes we heard about how the awkwardness of a hybrid setting reveals humanness. Talking all at once due to latency, speaking while muted, or unmuting in a loud environment without being unaware of it—all of this bring the actual person behind the screen, instead of all the buttons and interfaces, into the limelight. mood

Together, in the etherpad, we wrote down our own anecdotes of awkwardness in online hybrid settings and took turns in reading aloud about:

- Birthday parties over zoom in different time zones, in unequal states of sobriety and drunkenness

- Assessments with teachers confessing to being in underwear during the call

- Teaching into the void of cameras turned off

- and mandatory end of the year online dance parties among many others. From a slow activation, everyone was now itching to giggle and shake off the experiences. quoteAs Femke Snelting's quote emphasized, "we use our awkwardness as a strategy to cause interference, to create pivotal moments between falling and moving, an awkward in-between that makes space for thinking without stopping us to act." With this in mind, the facilitators guided us to find the recurring tropes—archetypes of online mishaps and failures—in our anecdotes. mood

After sharing our uncomfortable online experiences, we dived into the tactical part of the workshop — making intimate devices for a hybrid setting. With March snow steadily falling, we switched from the semi-distracting elevator music to a recommendation from the etherpad chat: the very best of Klaus Wunderlich. Chae demonstrated a prototype of glasses she made with window blinds attached to the frame. While wearing them, you can decide to open or close your blinds to light up a conversation. More kindred devices were laid out for us as inspiration, from curtains for your laptop camera, to analogue loading contraptions which you power yourself. Next to them, a wide array of gadgets and materials for building our own intimate devices. With zigzag scissors, decorative flower stickers and a little whimsy, we crafted filters and devices to test and share in a zoom call. As one could expect of a setting that embraces technological awkwardness, someone forgot to mute, and a dizzying cacophony of voices echoed throughout. mood

During the reflection of the workshop participants, shared everything from DIY amplifying microphones and catapults directed at your screen, to wiggly character filters dancing around your camera and masks which partially cover your screen. With a small intervention, a clumsy device, and embracing awkwardness, we were imagining alternative modes of togetherness online. This did not translate into the plenary talk of EXPUB, presumably because of the change of venue and seating arrangements. Nevertheless, we’ve come closer to understand what space, albeit temporary, intimacy can hold in hybrid settings. reflection

**Red Thread **

The workshop offered insight into potential ways of utilizing awkwardness to offer alternative ways of being together online. It opened up a space of sharing uncomfortable moments of a time we were all forced to have a solely online interaction with the world. Sharing awkward online anecdotes spoke to a facet of hybrid existence that is only ever spoken of informally, and never addressed practically. Yet the making of small clumsy intimate devices addressed this topics with a tactical approach. It encouraged participants to challenge the formality of online meetings, and interact with the screen and people behind it, in a more imaginative way. red thread reflection

**Repository **

Script and chat: https://pad.xpub.nl/p/awkward_hybrid_publishing

References from the workshop document:

- Collins, S. (2020). Intimacy: An Alternative Model for Literary Translation. English: Journal of the English Association, 69(267), pp.331–345. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/english/efaa033

- freeze.sh. (n.d.). Femke Snelting: Awkward Gestures: Designing with Free Software. [online] Available at: https://freeze.sh/_/2008/awkward/# [Accessed 9 Mar. 2023].

- Ahmed, S. (2004). The Cultural Politics of Emotion. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Chun, W.H.K. (2018). Queerying Homophily Muster der Netzwerkanalyse. Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft, 10(18-1), pp.131–148. doi:10.14361/zfmw-2018-0112. Event page: https://networkcultures.org/goinghybrid/program/

Blog-post: https://networkcultures.org/goinghybrid/2023/03/30/workshop-clumsy-devices-for-awkward-hybrid-settings-conference-report-day-2/

A living archive is also a dying archive

Starting from research questions surrounding the inherently ephemeral nature of archives that live on the internet, this expert session looks at the structure and classification aspect of an online archive, the care and maintenance it requires, as well as which parameters for curating content lie at the forefront of a truly accessible archive.

The session takes place on the mezzanine of Framer Framed which is an open space with a lot of natural light, it’s cold and even snowing outside as we settle into our seats. We are all seated at a long table with the facilitators at one end operating the projected presentation and the participants who fill all the seats at the table, facing the three facilitators. Sofia Boschat-Thorez, an artist-researcher and educator with a focus on knowledge organisation systems opens up the session with introductions. She is from Varia and Willem de Kooning Academy.

The session is facilitated by Sofia ( https://monoskop.org/Sofia_Boschat-Thorez ), along with Artemis Gryllaki ( https://artemisgryllaki.net/ ) and Karl Moubarak ( https://moubarak.eu/ ) from Hackers & Designers ( https://hackersanddesigners.nl/ ).

Practices of Streaming Resistance

Attendees around the table introduce themselves and their interest in the project one by one. Many of those in attendance work in or with archiving, right away it is clear there is a lot of interest and familiarity with the subject within this session.

The faciliators expliain that the research stems from the hybridity encouraged by the pandemic, the project began during a transitory moment of the pandemic when events were not fully taking place in person or online but had transitioned from solely online to hybrid settings. This is when the importance of digital archiving became increasingly clear, there was a necessity to be working primarily online. This created a production and accumulation of digital material that needed to be organized.

Due to this accumulation of hybrid material, the question became, how does this material need to be organized, what do we do with it and how do we think of accessibility in regards to it? We have been given access to a temporality that is more accelerated so new approaches to online archives and what becomes of them over the long term are necessary. Online archives are often lost when maintenance is overlooked, due to a lack of funding which makes it more complicated to remain focused on.

An example Karl shares with us of the issues related to the lack of maintenance/resources for online archives is the website Queering the Map ( https://www.queeringthemap.com/ ), which “is a community generated counter-mapping platform for digitally archiving LGBTQ2IA+ experience in relation to physical space.” When I search queering the map on Google among the suggested results are “queering the map not working reddit”, “queering the map how long does it take” and “queering the map not loading”. Karl explains that the site has zero maintainers and only one person moderating. It can take up to a year for new submissions to be published on the site. This exemplifies the temporality of digital archives, the concept of the living archive simultaneously existing as a dying archive. There are many digital archives that remain accessible but are no longer growing or being modified, situating them in-between living and dead, zombie archives.

Sofia, Karl and Artemis explain to us that their aim in the project was “not to reach a technical solution but to use this moment to create a proposal to implement reflections and interests.”

To achieve the aim of creating a proposal to implement reflections and interests to address living/dying archives the participants engaged in conversations, meetings and 1-2 day sprints of prototyping, transcription, coding and editing. They reflected on what works and doesn’t and rearranged the path accordingly.

The participants of the project were Margarita Osipian (The Hmm-platform for internet cultures https://thehmm.nl/ ), Angelique Spaninks (MU-Hybrid Art Space https://www.mu.nl/en ), Simon and Artemis (Varia- center for everyday technology https://varia.zone/ ), Karl (Hackers & Designers https://hackersanddesigners.nl/ ), Laurence Scherz (Institute of Network Cultures https://networkcultures.org/ ) and Sofia (Varia https://varia.zone/en/ , Willem de Kooning Academy https://www.wdka.nl/ ).

“It was a wild ride to find ways to organize and set a path and rhythm together with people from all different backgrounds and skillsets.”

MU Hybrid Art House’s event archive and exhibitions were used as a vehicle for all of their experiments. MU is considered the problem owner for the project and has 25 years worth of events archived. MU is located in Eindhoven, The Netherlands and describes itself as “all about art in the broadest sense of the word. Together with mainly young makers and a broad, international audience, MU defines the liminal space between ‘what art is and what art can be’.”

-

With three facilitators speaking to the participants as well as to each other, the session successfully feels more like a sharing of ideas rather than a lecture. The conversation shifts often and the focus goes from introducing the methods and aim of the project to discussing Eric Kuitenberg’s work on the relationship between memory and archives.

Kuitenberg explores the connection between living memories and digital archives in his essay Captured Alive: On Living Memory and Digital Archives ( https://nadd.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/en/articles/captured-alive-living-memory-and-digital-archives ). Due to memory existing in certain cultural contexts and situated in the biological body of those that hold the memories, different elements of an archive will recontextualize those memories. Kuitenberg writes “Memories evolve, mutate, blur, and are continuously re-contextualised by new experiences. Sometimes memories are forgotten, or are apparently forgotten, only to re-emerge at the most unexpected moment.”

For the team the question becomes “How could an archive also allow for recontextualizing within itself of one event through time?” The aim is to come up with a system of an archive that inspires fluidity of memory. This archive would need to evolve in relation to the different actors that are interacting with it. The relationship between the memory and the archival material is being recreated through time, an ever evolving archive.

It is at this point in the discussion that the participants are asked to share their thoughts which begins a discussion exploring of the definition of a dying archive. The question of the way a digital archive can be adapted to incorporate living memories is unfortunately passed over for the time being.

One participant asks “can archives sleep?” which leads to a discussion about dormant and active phases of an archive and how this can relate to it being an undead (zombie) archive. The idea is that a zombie archive is neither living or dead. Its accessibility makes it undead, but it cannot be modified or reactivated. There is also the question of retired archives, which would require maintenance in order to remain living. The mention of Erica Scourti’s project Dark Archives ( https://archiefinterpretaties.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/en/3-erica-scourti/dark-archives ) opens dialogue about the metadata of an archive being the shell or the trace of an archive, contributing to it’s undead status.

One attendee finds the metaphor of life and death applied to an archive absurd, stating “it’s just there”, the heated response from another participant is that this isn’t the case since it is being used. Another point of contention is the relationship between maintenance and preservation and whether an archive is living or dying. Karl suggests that maintenance is for the dying archive whereas preservation is for the living archive. Carolina, one of the expert session attendees, then proposes that an archive itself is a signifier of death and that preservation can be considered a material or passive activity and a living archive is one where preservation is more active.

The conversation then shifts to the question of navigating a digital archive, how does one’s path change over time and how do people get oriented. This introduces the question of classification and the importance of vocabulary. They state that a mode of classification is a way to understand and represent the world and that it is hard to find ways to work beyond it. How does one escape fixed classification? To play with classification may mean to play with structure. Online archives can be organised by the vernacular mentioned in the content, this isn’t possible in the same way for a physical archive and allows for the reactivation of the content within different contexts. What exists in the archive is reactivated and the material is put into relation with each other digitally.

Due to a person’s subjectivity changing over time, tags might shift and classifications become quite loose. “There is something quite slippery about having to tag and annotate items in an archive.” Something as simple as using dashes differently or using different spelling can affect the way archival material is tagged and subsequently classified. The subjectivity of a person has an impact, they have their own history and ways of writing and therefore the way the archive is presented will be impacted.

The challenge then becomes, what choices does the team want to make with tags (such as vocabulary) that can break from the normative and instead be rooted in a small group of people. Perhaps as an attempt for human influencing being made obvious, searching for a mode of classifying that will make subjectivity appear at the forefront. The imperatives are different when you are a part of an institution that requires other institutions to understand the way you are classifying your content. The team asks itself “how can we shift from an authoritative prefixed navigation logic and open up the structuring process to the viewers?” How can they combat the tyranny of structure in digitization when they are inevitably locked in clear delimiters for tags?

It’s at this point that a participant brings up what they refer to as the elephant in the room, the fact that digital archivists have to rely on database centers. The team responds that their aim is for the work to be done without databases as much as possible, this is conceivable because they are operating as a smaller institution and therefore have more time and resources for experimentation, unlike bigger institutions.

The conversation shifts back to classification, what methods and tools can the team utilise to open up the structuring process to the viewers. They suggest that if they “can reverse, bring subjective method, viewers can bring their own ideas about what happened” and ask if this something that is also important to keep as a knowledge or a memory.

Finally, the facilitators explain more in depth how their project with the MU Hybrid Art House ( https://www.mu.nl/nl ) materialized and what approaches were preferred. With the scrapping of MU’s existing archive they bypass the database and work on what they playfully call MUmories. With their bootlegged archive of MU they have the code and content and are able to then enter it in different ways. They played with the content by arranging it as image only, tight and as a wordcloud. They explored reclassifying the archive as what is there as material, what can be used as digital material. Looking without text by arranging it as image only can bring up new memories or questions.

At one point during the session Karl as well as many in attendance take notice that the mezzanine is incredibly cold, this is then somewhat rectified by a space heater and hot tea brought over by a kind soul from Framer Framed. However, the temperature does seem to have an impact on the energy levels in the room.

By talking through the MU archive the topic of the precarity and fluidity of memory resurfaces within the discussion. The team recognized that when remembering different events some may experience gaps in memory, consequently, existing memories of these events may be scattered throughout the various people who attended the event and those experiences might not have been documented. They wanted to find a way to gather and attach those individual accounts of an event to different items in the archive in order to progressively remove the need for more factual information such as pictures and titles. The team explains that they wanted to focus more on the attendee’s takeaways rather than objective facts. They wanted the selection of what is considered important to not be done by the institution but by the people experiencing the event. The aspect of processing memory becomes significant because the information that is collected would then be based on what is memorable to the individual.

According to Kuitenberg “the living archive required a set of tools that support and enable continuous reinterpretation of archived materials, including rich media sources such as audio and video recordings.” It makes sense then that the team decided to focus on oral testimonies. They explain that oral narration can be utilized as a response to the dying archive, when the archive starts to rot the testimonies of memories remains. This would be considered zombifying the archive, creating an undead and unfactual version of the archive. This then deserves and requires as much digital care as the traditional archive.