chapter

Irene de Craen

3 July 2024, 10:00 AM

Introductions

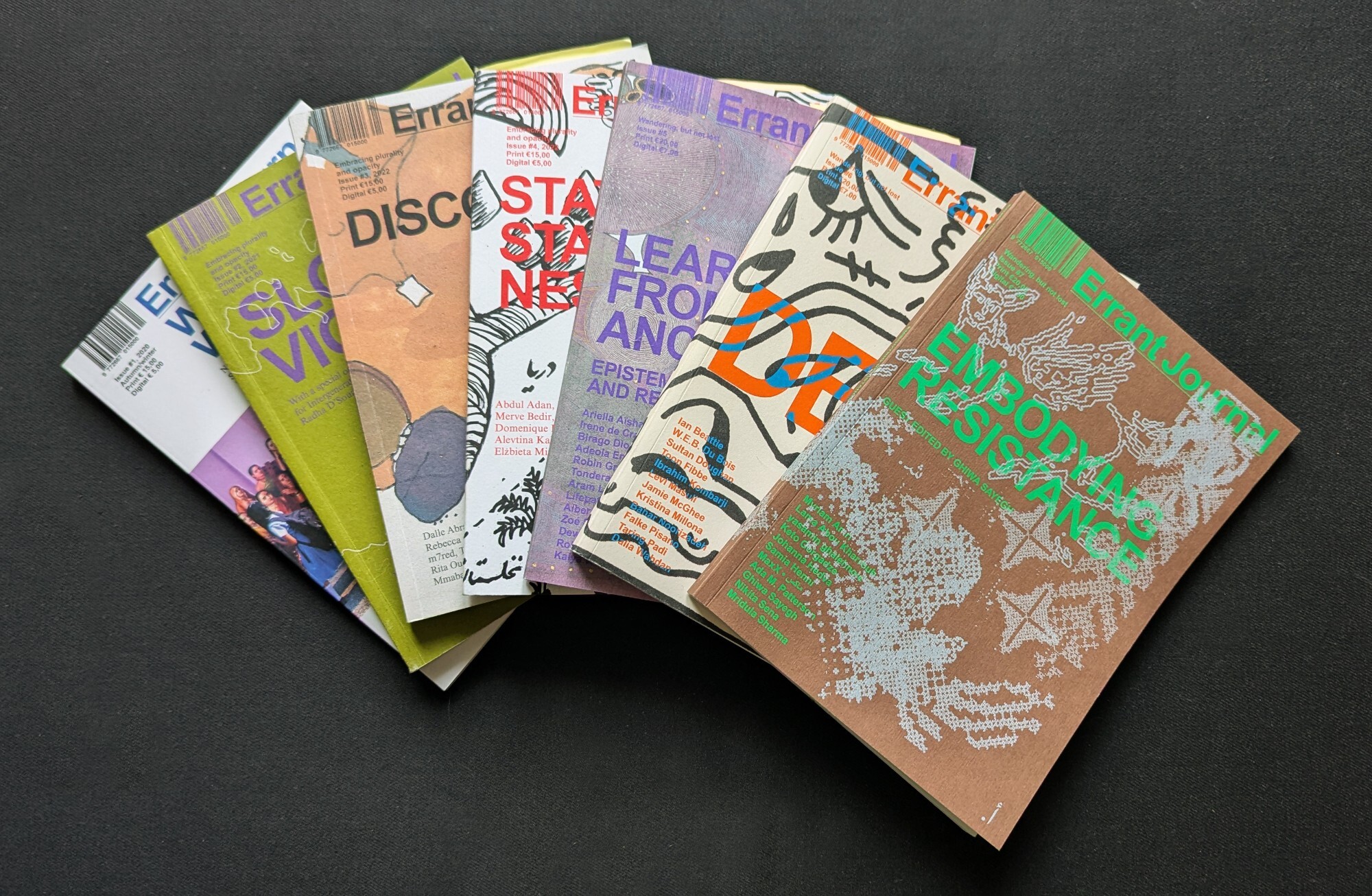

00:45 Before getting into more specific politics, I always want to explain how and why I started Errant. I have a background in visual art; I went to an art academy and studied art history. I was the artistic director of an art space and was making exhibitions. However, this format of telling a story through an exhibition is unsatisfactory to me because I’ve always been interested in combining different voices and non-art objects. The white cube or art space diminishes this difference: when you enter an art space, you look at everything the same way, when you put something that is not an artwork in an art space, it becomes an artwork (which is also thanks to Marcel Duchamp, of course). At the time, I was reading Édouard Glissant, and he writes about sameness and difference in multiple ways, about how our Western culture can diminish difference and work towards sameness, which is very destructive. So, I stopped working as an artistic director. I’ve always liked publications. I also used to work as a journalist and made publications to accompany exhibitions. For me, this format is a way to combine more differences, and this is especially true with language. We will get into specific things I do with publishing later.

In other words, I see Errant Journal as an alternative publishing practicesalternative to the exhibition format. But this got me into trouble when a funding application was rejected for this reason. I’ve been rejected for funding many, many times, but one of them happened in the beginning when I said Errant Journal is like an exhibition. And they were like, no, it’s not. So I thought about it and realized that for many people, an exhibition is a collection of images — something that is visual. For me, an exhibition is something that tells a story and is able to do this from different perspectives. So I thought that was a funny experience, sometimes you learn from rejections.

Why: Politics of publishing

03:59 You already mentioned a few inspirations or references that guide your practice, namely Glissant and his “Poetics of Relation” and the idea of opacity. What other references, materials or theories inspire your publishing practice?

04:24 Well, apart from Glissant, there are a lot of other, mostly Latin American decolonial thinkers, as well as Ariella Azoulay, who’s also very important, especially her book “Potential History”. Her background is in photography, so she talks a lot about images and archives, especially the violence behind archives and structures. Of course, publishing, writing, and communicating in the English language is not ideal, and I always say, maybe at some point, I’ll be fed up with all the limitations of publishing, and I’ll move on to another format. politicsBut I think there’s a lot to be done within this format, a lot of opacity is important, a lot of refusal, and a lot of subverting in how you put things together. I find it interesting because by doing that, you question how we think about knowledge and how we think about what is important and what is not.

05:53 Amazing, thank you for that. So, we are just moving on to our other part, which goes through threads on the “how” of the infrastructures of publishing. How does that process of seeing a publication as an exhibition space (and much more) look like to you? Do you also take time to refuse certain traditional workflows? And how is the idea for the themes born, developed and then published?

06:52 I think there’s a lot to your question. The way I set up Errant, structurally and organizationally, is also very important for the content. There is the editorial process and how I approach each contribution, and then there is an umbrella over the process of how I approach the object of the book and how I subvert that. So, there are different layers to it. To start with organizational aspects, I was the artistic director of a very large space before I started Errant. conditions of workIn my experience, the bigger the space, the more limiting it actually is. One of the things that constantly frustrated me was that when we didn’t have any budget, we still needed to fill the space, which forced artists and others involved to practically work for nothing. This is the kind of situation that is causing burnouts, and I think it is ridiculous to have to perform for the funders in this way.

So one of the things I’m very happy about with a publication is that it doesn’t have a space. Especially being an independent publisher, there is no space to take care of. sustainability of workflowsI also made sure that Errant is not published periodically, I publish whenever the hell I am ready to publish — and this is a structure that I’ve set up that funders find a little bit hard to understand. When you are interested in including certain voices, you should also give space to people to have those voices. I always use the example of the second issue, which was about the environment, and it was delayed because one of the contributors was in a court case against Shell. So this is a good reason to extend the deadline, and because there is no space, you can create at your own pace. It is the same with Gaza: the last issue was delayed a bit because someone was trying to get a friend out of Gaza. emotional labourI’m trying to set up an organization that can make space for people’s lives, and the issues people are dealing with that are usually directly connected to (geopolitical) issues Errant aims to address. In this way, the work is not removed or cut off from the actual lives and work of people I work with. Do you want to know more about how I work with the actual contributions or with editing?

How: Infrastructures of publishing

11:00 Yes, I think it’s nice to know a bit more about the workflow that leads to the finished publication, but I think it’s also interesting to go into what kind of tools are important for you, material or collaboration-wise. Is there a specific guide or workflow structure that guides these collaborations, and how do you find collaborators and build up this process?

11:40 Having any tools or guidelines would be very anti-Glissantian! Each process is individual, although, of course, I learn certain things that work or do not work. I try to build very personal relations with everyone I work with, especially to give space to what I’ve just mentioned. For instance, there recently was someone who told me that they would not be able to write, the reason is a very private and personal story, which of course I will not go into, but I’m very happy that people are coming forward so it can be discussed and I can support a contributor in the best possible way. We ended up with an amazing contribution!

It’s a very important and delicate relationship. I used to be an editor for different magazines, and I’ve worked with people over email without realizing that they were many years older than I thought for example, or even that they were a different gender! And I think in the work that I do, that’s just not right. toolsWho someone is really informs the editing process, and every process is unique. So I have conversations with people in real life, if possible, but mostly over Zoom. This is still limited, of course, but at least I get a bit of an idea of who someone is. It also makes the process much more fun to be honest.

14:56 I remember last time we had a conversation, you talked a lot about the decolonial position that Errant Journal takes and the way you provide a platform to people from the Global South. How do you see those infrastructures that we can access in the Netherlands or Western Europe with building up this anti- white-cube European-centric thinking within a publication that is based in the Netherlands?

15:34 I’m very much aware that my position is still that of a Western white academic, and to me this means I have to constantly challenge the way I think. co-publishingGlissant talks about how every exchange with another, changes the self. That is why it is important to talk to people so that I practice listening, which is a decolonial practice. You know, shut up for once and listen to what people have to say. Currently, I’m working with Ghiwa Sayegh from Kohl Journal, which is a Lebanese open-access publication by anarchist feminists focused on the MENA region. It’s fantastic because I’m learning a lot from how they are approaching the editing process.

Yesterday, I was looking at another magazine that hadn’t heard about yet. conditions of workThere are a lot of magazines out there that say that they’re giving space to ‘other voices,’ but one of the problems that I see is that a lot of these publications don’t pay people. They say they are open to everyone, but by not paying people, you’re not open to everyone, you’re open to people who can afford to work for free, which is a very small segment of our society. It’s very important to me to pay people, and that’s one of the main focuses when trying to reach ‘other voices.’ Although I don’t think I am able to pay people the actual worth of their work, I try to do my best.

18:21 You’re right. I think that always ends up being omitted. As you said, it’s nice to say, “We open this space”, but then how open is it if it’s not paid work? You also mentioned the subscription model that you’re investigating to circumvent certain funding structures of the Netherlands that divide publications, art, and spaces in very tight borders. How do you keep the sustainability? How have you explored these different models to ensure that Errant Journal can continue?

19:01 That’s also funny — I find it strange that in the funding system of the Netherlands, even the smallest cultural organizations are supposed to have a business model. My business model is not a very traditional one. I always take it slow, one or two issues at a time, also depending on what else is going on in my life. I do look ahead, of course, but I didn’t set it up to think that things are going to be a certain way because it doesn’t work like that. This has been a reason why I’ve been rejected by funders as well, for not having the right business model. I find that very funny because, again, the way we work and the way we live are being pulled apart. I’ve been living like this (as a freelance cultural worker) for over twenty years: I can look ahead for a few months, but not more than that. So I started an organization, it has no overhead, no buildings, and no staff, and yet I’m expected to make a ten-year projection? business modelsI was told that Errant Journal wouldn’t last because it doesn’t have a good business model. I found it very strange because the only reason Errant Journal would stop is if I don’t feel like doing it anymore. Financially, I can keep going, especially with this model, because I haven’t set myself up to produce a certain amount. A distinction is made between organizations and artistic practice, while for me, this doesn’t exist. This is my artistic practice, it’s just that because of how things are structured, I am required to have a board and a business plan etc.

When I registered myself as an artist/freelancer back in 2001, the guy at the tax office said artists are funny because they never go bankrupt. As long as you’re alive, you can keep going. Of course, you can file for bankruptcy as a freelancer as well, and some people do in some situations. But he’s right: as long as you are alive and you’re able to work, then you keep going.

21:56 I imagine that you can find other ways to sustain this practice by not having a very strict deadline.

22:11 Yes. I don’t know if you’re also a freelancer, but in my experience I could meet someone tomorrow who has an interesting idea for a collaboration for instance. This happens to me all the time, and I’ve been doing it long enough to know that, although it’s not a business model, it is sustainable because it has been sustaining me for twenty years!

Who: Community of publishing

22:35 That’s interesting. I think you’ve mentioned your collaborations, your community and this network that enables Errant Journal to continue and also shape itself in different times and spaces. How has this sort of community of collaborators or readers been created? How do you relate to them?

23:17 Sometimes I get questions such as “How did you find this or that writer?” Well, there are several ways, but one of them is that I will remember something that I read fifteen years ago, and I will just go look for a person who can write about it. The example I often use is also from the second issue. I was looking for a title for the Journal, and one of the names that I considered was Tuvalu. Tuvalu is the second smallest island nation in the world (I suggest to Google it and look at some images!). The country consists of a group of atolls, and they are all sinking because of the rise of sea level due to climate change. I believe the total population of this country is around 11,000, and they’re on tiny strips of sand in the middle of nowhere while sinking.

Well, this just grabs my imagination: there is so much going on in that situation. I wanted to find a person from there to write about Tuvalu. You can imagine that when a country is that small, it’s quite hard to find someone who is both willing to write and has at least some experience doing so. Certain activist groups are working in that part of the world on climate change, and I started writing to all of them because I had one name at some point, and he didn’t respond anymore. I also reached out to those organizations via Facebook Messenger, and at some point, I got an email from the same person who didn’t reply to me earlier. He said: “You must really want me to write because you’ve now emailed me through three different organizations” — it turned out he worked for all of them, and these are all very small organizations, so he was getting all the emails! So, co-publishingI guess one method is spamming the hell out of people (although it was completely unintentional to be this annoying!). Nowadays though, since the network has grown, it’s also through referrals. And there’s the open call, although open calls are also very flawed, but I’m still using them.

26:17 Can you expand on the flaws of the open call?

26:29 The space I ran before was also a residency, and we had an open call. But when you’re looking for ‘other voices,’ business modelsan open call is not necessarily the best way. In my experience with the residency, 99% of applicants will be white artists from northern/western Europe, all making the same kind of art (and calling it experimental). I also see other organizations doing open calls, and spreading the call widely and then using the amount of people that respond as a sort of marketing tool or indicator of their popularity. “Look, we had 700 people reply.” But what’s the point of that? Again, why this performance for the funders? When Errant has an open call, I actually don’t promote it that much because I don’t want quantity, I want quality.

The process of open calls is also problematic because people can spend a lot of time on a proposal, only to be rejected. With Errant, I aimed to make the threshold very, very low: I just ask for a proposal of 300 words. There’s no form or format is has to be in, and I sometimes say it’s basically an email — which I actually also accept. It’s all about the idea, and I don’t care about anything else. I just need an email with your idea, that’s it. And a few references and a bio so I understand where the idea is coming from, how it is situated within someone’s practice and the world. For all the people who are constantly applying for things, the process is so tiring to get rejection after rejection, and I hope to make it honest in that sense. There are many people I’ve started a working relationship with after I’ve rejected them because then they come back for collaborations, and I’m always open for it, or they ask me to look at a text they wrote, so I try to do that.

29:19 I always think it’s also about balancing between the open calls and the invitations because inviting also keeps you within your frames of reference.

29:33 Well, I always also invite people directly. But I still do the open call, because that’s how I get people that I would otherwise never have found. It’s funny that you can also see how the call spreads and develops — for the previous open call, we had a very large amount of architects apply. There is a small fan base in Cairo and the Philippines. So it’s quite interesting to learn a little about how people find you.

30:14 You mentioned this idea of the editor and the traditional way of seeing it as someone who’s always right, but you were also trying to defy that. What are the ways that editors can be creators of community and art? Can they be or not?

30:50 Well, definitely, I think this is important. I’ve been told that sometimes people can be intimidated by me, which I find both sad and a bit funny because I don’t think I’m intimidating at all. I try to be very careful in creating a space where people feel that they can contradict me. Please do! If you think that I’m wrong, then for God’s sake, tell me!

As stated above, I’ve been working with Ghiwa from Kohl and they organize what they call ‘writing circles’ through which they make their journal collectively. I have always been a bit of a loner, but working collectively is something that I am definitely considering for Errant. I have to be honest, groups kind of freak me out. communityI think making publications is the world of introverts, but I also talk to people who do translations collectively and I think that is a very good way to think about publishing. I think the outcomes of that could be very valuable, so it’s worth a try.

32:53 That’s interesting: the idea of the publication, as you mentioned, is such a collective work, but then it’s also the work of the introvert somehow.

33:12 Before I started Errant, I realized I had to be part of book fairs. I hate fairs, they are horror situations for me, but I realized I needed to take part in them because they’re really important to get your name out there. At the very first book fair, I realized that book fairs are different from art fairs, because they’re all introverts, and only very few are chatty.

33:48 Folks just want to look at the publications, right? Book fairs end up being important to reach your readers. You talked about the way that you communicate with contributors of the magazine. Who are the people who read Errant?

33:50 That is nice about book fairs because although I’m a loner, I do meet people who say they’ve been reading the journal, and that is great, those are the kinds of conversations I’m happy to have.

33:52 Some positive reinforcement, too.

33:52 I do need it! Because otherwise, you go mental. My idea of the audience, from the start, was twofold, which is also reflected in who I am. On the one hand, it’s artists, people interested in the visuals and thoughts, and on the other, academics of all sorts of disciplines and I found that it works exactly like that, Errant Journal is very popular among art students and artists. From the sales, I often see orders from universities; then, occasionally, I look up to see who the person is and what their research is about. It’s fascinating because sometimes it’s the weirdest research! I’m very happy because it was exactly set up like that.

Discussion

41:34 Thank you. I’m now just going to ask the rest of the group to see if they want to say anything or have any questions.

41:36 Hi, nice to meet you. I’m Janez from Aksioma in Slovenia. I think it’s interesting that you said you were leading a gallery as an artistic director, and the limitation that you saw in such a format to create knowledge or to deliver it. In a way, it’s similar to the path I’m going through. We have a gallery space, but we do more and more publications so I totally understand what you want to say here. As for the publication, I have to admit that I did not know much about you, and I did some investigation before this meeting. I see that you do podcasts too. I’m wondering if, after so many years of experience as a publisher, you have perhaps found other kinds of limitations. Did you, after investigating so much, find a limit? Do you ask yourself in what ways new technologies can open different horizons and expand the concept of publishing?

41:56 Yeah, I totally get what you mean. I always say that at some point, I will come across the same kind of wall, but not yet. Obviously, there are some limitations that have been there from the start. Language is the main one currently. We are still communicating in English, which is a colonial language. Yet, for me, there are so many ways to play with it: the ways with which we can subvert this, do these things differently. There is plenty of room for looking into things. Maybe if I do all of these things in the next couple of years, I will be fed up with it. So, no, I do not see this as a real limitation. We’ve been able to find satisfactory solutions or experiments for each thing so far.

As for the second part of your question: traditional publishing practicesI am absolutely a book fetishist. The material and the paper are important to me. And I always try to play with that. We are the only magazine or book in the world that has a smell. Not all copies have a smell, and on some copies, they disappeared, but two of them still have their smell. For this I worked with Mediamatic in Amsterdam. To me, this is also about how we communicate language and a story. I have not advertised the smell because I kind of like how people get very confused. For example, the second issue smells of cucumber. It’s very light, but it’s there — if you had a book in your bag for a while, and you open the bag, that’s when you smell it. I’ve told some people this, and they said, “I was wondering where that salad smell came from all the time!” So, if we are talking about expanded publishing, this is a fun way for me.

44:12 Hi! I am thinking about what you said about your business model being precarious. On one side, there is a limit, of course, because it’s a fragile model that can probably not guarantee continuity. On the other side, there are also characteristics of independent publishing, so I was asking myself if you were fine with not being stuck in this situation that it can be a limit but also an opportunity. If you are interested in broadening your audience and communicating with the bigger community with your message and content, how is this possible with this kind of limitation?

44:43 I really want to reject the notion of Errant having a precarious or fragile business model. In fact, I was saying the opposite of this earlier. Sure, there’s not a ton of money, but this does not mean it is a precarious model. It’s my life’s work, and I will not stop unless I want to or unless I get hit by a bus. If you really want to support Errant Journal, please subscribe. Errant only has 44 subscribers so far, which is not much at all, but from that small amount, there’s a monthly revenue that I can count on.

Of those 44 subscribers, 11 of them are universities, and they pay a lot more. I’ve also been surprised, actually, at how much revenue I can get from advertising. And then as Errant grows there are (big) organisations reaching out and saying they’d like to collaborate. I have to see how to handle that, because I want to remain independent. governance and ownershipBut I sometimes feel the ways of moving forward are endless. So, I don’t think these models are fragile just because there’s little money or its irregular. We have been taught to think like this because that’s the neoliberal, capitalist way; always more and bigger. As you were talking, I was also thinking about how banks are not considered precarious or fragile at all, and yet governments have to save them by billions every couple of years. So, who’s the fragile one? Obviously, there are differences, I’m not a bank, but you know where I’m getting at: it is a perception of how you see precariousness or fragility in business structures. So I resist that, as I do with many other things.

47:27 The idea of precariousness is also about scale. I think the biggest question when it comes to subscription models or, I guess, alternative business models is to what extent they can be scaled when you start having more employees and more collaborators. And how do you ensure that you can keep going, and what about older people? Can they keep going? This is a conversation that we’ve also been having with others about ideas of care and self-care or the so-called exploitative cultural industry that claims to be interested in the care but then expects their workers to just keep going. Of course, it’s different if you’re working on your own compared to working with others. So I guess when it comes to scaling these things, how can you maintain or how do you see this non-fragility or resilience that you do see in these smaller independent publishing? Can they be scaled? Should they be scaled? Can you build from those more social and personal connections in a wider network? This is also what we’re sort of doing with the consortium, putting together resources and knowledge. I guess this may move into the final question about the future of publishing. What direction can these models take?

49:28 Well, there’s growth of course, the sales of Errant are going well. But I think we should be careful of using growth as a goal or a measure of success. I think that’s the road to possible exploitative structures. At the moment, it is just me and the designer and I will not hire anyone else until I know that I can offer them fair pay. I had an editorial assistant for four issues because we had a subsidy. So then, from the beginning, I just communicated that she was paid fully, she was paid more than I have ever paid for that kind of job for those four issues. governance and ownershipI will not work with interns even though I’ve had a few interns who came to me by themselves and sort of begged me. I find it very problematic because, so far, all interns and voluntary assistants who said they want to have experience in publishing have all been white. They’re all people who, for one reason or another, can work for free. Sometimes I will agree to that, because they want to gain experience too, but I still find it problematic. I’d rather do all the work myself than exploit someone, that’s just the basics of it. Unfortunately, I see how many other organizations work with interns and it’s so exploitative. I come from a working-class background, I was never able to do an internship because I had to work to pay my rent. I always saw my fellow students do internships, and they all have very good jobs now at big museums. So, this is a very exploitative model that I refuse to engage in. Unless people sort of throw themselves at me, then it’s hard to say no, but still, I’m trying to be cautious.

52:38 Hi, I’m Tommaso from Network Cultures. Firstly, thank you so much for all the very thoughtful insights. I think the reason why we started thinking about expanded publishing is not really because we felt limited but also because we felt the need to expand through the authors who would come to us saying they have some limitations, especially when we work with artists or artistic research practitioners, paper publication sometimes can be limiting. So my question is, have your authors ever felt limited in terms of paper publishing? Also, let’s expand a bit on “The Subversive Publishing Guide.”

54:08 As for your first question, I’m used to working with artists because of my background. I’m trying to create a situation where people feel very free to just come with me with whatever, including artists wanting to expand on the publishing platform. You can leave it up to artists to come up with ideas. I was very happy that during the last issue, we published a sound piece from someone who responded to an open call with digital objectsthe idea of a sound piece, which in a way is separate from the publication, but it’s still part of the publication. So I thought that was nice and was happy to be able to give the space to this person to produce, and I was able to pay them for that. So, you can let the artist or the contributors lead. Sometimes, the limitation is cost. But overall, the people I work with are very happy to have their work appear in a physical paper publication.

Thank you for mentioning Subversive Publishing. That was a commission from Framer Framed to me as a person, but all the ideas in there come from Errant Journal. In it, I don’t talk of limitations, but rather of things that you come across when publishing that make you think about how to deal with them, especially with the background of politics and decolonial ways of thinking. For instance, when it comes to images I absolutely will refuse to pay for certain colonial archives or museums, like the British Museum. They steal artefacts from all over the world, and then when you want to use an image, you have to pay for that. F* them, no way. Redrawing an object or image is a very lovely way of circumventing this particular limitation.

Another example is ‘citational rebellion,’ inspired by Sarah Ahmed. She wrote a very cool essay on her blog about how citation works within knowledge creation and publication. Then inspired by Zoe Todd, who wrote about Ahmed, politicsI’ve come to realize how citations work to legitimize the work of some, while ignoring those of others. For this reason, Todd describes how she will only reference Indigenous thinkers. Her point is that the white men that are always cited — she talks about Bruno Latour specifically — were not the first to think of something. Nine out of ten times, they were not. And you can find an equal source from someone else, someone of colour or a woman for instance. I currently want to expand the Subversive Publishing series. I’m going to apply for funding because I’m working on open access, I want to make a collection of texts that go into this a little bit further and are also an umbrella of how I think about publishing and Errant. I hope to do that next year.

59:04 I read on Errant Journal that you’re building some sort of ecosystem of different media, you’re using podcasts, but also public events. Sometimes, public events are a way to support the publication. I was curious to know and to understand better the function of this ecosystem and how you build it, and how all these things collaborate.

1:03:11 Well, the podcast is very easy. I was working behind the scenes on Errant for over two years. I was due to publish the first issue in April or May of 2020 and then the pandemic happened. I had a complete meltdown because I had just quit my job, because the idea was that I would be travelling to book fairs and stuff like that, and then everything fell apart. That was also funny because I was talking to other publishers, and someone said, “Don’t worry, Irene, you don’t have a building to pay. You don’t have any revenue from last year to compare this disastrous year with.” So the podcast started because I felt I needed to have online content. Now, I use the podcast to have very helpful conversations, it’s great to talk to people. It’s more of a research method, and how the other things come to be.

As for the public events, like I said, I don’t really like doing public events. I just cancelled one actually. In my many years of doing public events, emotional labourI decided that I don’t want to talk if I don’t feel I have something to say. Sure, these moments are important for selling Errant and get more subscribers, but I didn’t feel I had anything to say that relates in a meaningful way to the world right now. The genocide in Gaza is the main thing that is on my mind these days, so honestly it felt wrong to organize an event to sell my magazine or talk about anything else, so I cancelled it.

1:03:35 That’s really important. It also reminds me of a quote from a Portuguese writer. He says, “I don’t want to write if I don’t have anything to say”. So it’s the same.

1:03:36 I think we should all do that. Again, this comes back to big burnouts when you’re planning an exhibition, and you don’t get the money, but you still have to do it. Somehow, we have to find ways to stop doing that and the same goes for publishing. We all know we love it so much, but it’s incredibly polluting. So, if you don’t have something good to say, please do not publish. Please do not cut trees.

1:04:01 The more you talk, the more I relate to what you are saying. I haven’t done a public presentation for over five years now, I am detoxing. So, I also lost my status as an artist with the Ministry of Culture in Slovenia and I’m happy I’m free. I’m not an artist anymore! We should meet.

There is one thing that actually struck me, a similarity between your way of doing and mine. And it’s not necessarily positive, at least from my own point of view and interpretation. When you talk about the organization of your work, it sounds a bit self-exploitative. In the sense that I will produce until I can, you do your website on your own. You start the podcast… Believe me, I did the same and I’m still doing the same. But yesterday evening, we were discussing informally here, and we were asking ourselves if when it comes the time, where do you see the border beyond which you don’t want to go? Let’s say, perhaps during a collaboration, an author is too invasive or too controlling. How much are you ready to let it go if, for example, the proofreading isn’t perfect? So what is the mechanism of self-defence in order not to be exploited by others besides the self-exploitation that you are ready to deploy?

1:08:09 Thank you for recognising my self-exploitation! This is also why, in the past, I’ve burned out many times, which is why now I just cancel events if I don’t feel like it. In the Subversive Publishing, the centrefold has twenty points to consider if you’re publishing subversively. It’s meant as a manifesto of sorts. One of the points is ‘consider not to publish,’ which we already discussed. Another point in the manifesto is to make sure you’re having fun. So, my main red line is that I have to enjoy the process. It’s stressful, there comes a point when I’m completely freaking out, but I’ve also learned to press pause now and then. sustainability of workflowsMy business structure allows for that because there is no pressure of time. So if I’m not enjoying myself anymore, I know I need to take a break. So this is the way I do self-exploit, but as long as I’m enjoying myself, as long as it’s enriching me, I’m allowed to self-exploit myself. That kind of self-exploitation will not lead to burnout, or at least that is what I think, because I’m just a hypersensitive person. This is why I like to stay at home and avoid public events, I get overwhelmed very quickly. I thought when I was doing the interviews for the publication; it was nice that came up from other people as well, the fact that we have to enjoy it. Otherwise, there’s no point. So, I keep that in mind. I say no to things that other people would not say no to, like money, for example. Sometimes, I really don’t like the person or the organization, or sometimes, I think it’s going to give me a lot of stress. I think they’re going to ask me things that I’m not comfortable with. So you know what? No. I’ll figure it out another way.

What: Future of publishing

1:09:12 Thank you. I think it’s great that you mentioned this idea of tuning into our intuition when it comes to collaborations. Going into our final question, which concerns the so-called future of publishing or trying to define together what expanded publishing could be and is — this idea of the future is perhaps difficult to pin to, but if you’d like to formulate your own ideas of what that could be? What are the most urgent aspects that you think should be addressed in this future of publishing, if we can call it that, or the urgencies of publishing right now? Should we leave the future and concentrate on the present?

1:10:26 I could be very cheeky because, from the colonial perspective, there is no future, this whole concept is fraud. But I won’t go into it, you can read the first issue of Errant; there are some thoughts about that. Maybe the future for me is not so much about technical development or progress in a traditional sense. politicsHowever, the process of learning to give more space to fit the politics of what we are trying to do into the working methods, I think this is very, very important. This comes down to giving space to “other” voices, and the question is, how do you really make space for that? I am talking about how I organize things and how I see them, and I have to fight for that. So far, people don’t get it. They don’t get that this is the only way for me to move forward. Of course, privately, I go through depression, and burnout, but it’s not just me who’s hypersensitive, it is everyone that we work with in the cultural field, especially those who have to deal with real precariousness. Art or cultural sectors have been too bent with political wills, especially now when we see the direction taken to the right. We have to resist this, which we can do by ourselves. Doing these very small things, little subversive acts is resistance. Things I have been developing and thinking about last year are definitely not done, so I keep going, and I am planning to publish more about it and hopefully infect other people with some of these thoughts.

1:12:54 Thank you very much. I think this was a very good answer, like refusing the future but with a focus on what we can do right now, collectively. I think these acts of publishing are resistance. This resonates with us very much.