chapter

02 Annette Gilbert

Affordances and Limitations of POD Platform Publishing: Findings from the Library of Artistic Print on Demand1

Expanding Publishing: From Fordism to Toyotism

It was not the perfection of digital printing technology that made print on demand (POD) a success, but a radical rethinking of the printing business and a complete reorganization of all related workflows. After all, it was no longer a matter of printing a single title in a large print run and then delivering the product on pallets to a single customer address, but of printing and shipping a large number of different titles, with only one copy of each title in extreme cases (which were to become the rule). This “profoundly disruptive” change has been compared to the transition from Fordism to Toyotism in the post-war period.2 But it was not until around 2005 that the POD model gained truly revolutionary momentum with the establishment of POD service providers such as Blurb and Lulu, which focused primarily on the mass market and the end consumer, especially first-time authors. As a result, ordinary people with no knowledge of design, printing, or bookselling can now create, publish, print, promote, and distribute their works—not only in the POD provider’s own online store, but also, if they want and once they acquire an ISBN, worldwide in brick-and-mortar and online bookstores to which such POD service providers are connected via Ingram and Amazon.

POD: Publishing Made for Everyone

What Clay Shirky provocatively postulated for digital publishing has since become true for the world of printed books as well: “That’s not a job anymore. That’s a button. There’s a button that says ‘publish,’ and when you press it, it’s done.”3 Shirky was referring here primarily to the world of the Internet. But this button also exists in the world of POD providers. In the case of Lulu, for example, it literally says “Confirm and Publish” (see fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Button “Confirm and Publish” on Lulu. Screenshot.

By reducing the once mighty publishing apparatus to a single button and making it available to all, independent of purse and gatekeepers, bookmaking became child’s play. This is also reflected in the names the platforms have given their offerings, such as “BoD Fun” for BoD’s basic product. And unlike the typewriter, mimeograph, copy machine, and home printer, that were once the first choice of self-publishers, POD publications are industrially produced, making them look like “normal” books and giving the impression (at least to the lay person) that they are on a par with regular bookstore products. All of this together has caused book production to virtually explode, and self-publishing has, as Timothy Laquintano states, “move[d] from the fringe of the publishing industry to become a small and fluid part of its core.”4

Platformization of Publishing: Providing Infrastructure for “the Whole Thing”

But there was another decisive factor in POD’s road to success: POD service providers do more than just print. They also equip their stores with “accessible and trusted payment systems” and handle shipping and logistics, finally solving the persistent problem of distribution, “that had made self-publishing and finding an audience untenable in all but the most extraordinary cases in the twentieth century.”5 Because these POD service providers offer everything in one place—from finalizing a print template and digitally listing a book to producing and shipping the first copy through to handling the global logistics of book sales, payments, taxes, custom duties, and royalties—the term “print-on-demand provider” does not adequately describe them. Rather, they provide an infrastructure in the form of a platform via which these services can be combined, coordinated, and offered as a package. POD is therefore, as Silvio Lorusso states, “not a new technology in itself, but a fruitful combination of existing ones”6 and their integration into a complex post-digital ecosystem of book market, e-commerce, and logistics infrastructures. It was this dovetailing that allowed Eileen Gittins, Blurb’s founder, to say, “We’ve deconstructed publishing.” After all, Blurb has succeeded in

not only disrupt[ing] the business from a “who gets to make a book,” but also the distribution model for how books are sold and discovered. […] So what we are now is a technology-enabled publishing platform, so that people can self-publish, soup-to-nuts from creation through marketing, distribution, fulfillment, e-commerce, the whole thing.7

Standardization: Enabling and Restricting

Unlike the production and distribution process, POD does not revolutionize or expand the book itself. Quite the opposite. The quality standards for production and the choice of materials and design features have decreased, especially in the low-cost segment for everyone. For example, Lulu currently offers just four types of paper and sixteen book formats (see fig. 2). Silvio Lorusso identified this dilemma early on: “[I]n order to produce unique copies, paradoxically, they [POD systems] enforce the limitations of mass production by applying stricter standards.”8 It is this standardization that enables automated and cost-effective production, as well ensuring the print job is executed as consistently as possible across a global network of partners.9

Fig. 2: Lulu’s custom book sizes. Screenshot.

But that says nothing about the actual latitude that POD leaves for the development of one’s own expanded publishing strategy. Oulipo is probably the clearest proof that compelling artistic solutions can be derived from a constraint. The history of printing has also shown time and again that it is less the companies and their inventions themselves that break new ground, than their users. This was already true for the Xerox machine: “[D]espite its banal original as a time- and moneysaving office technology, the history of the copy machine has been deeply shaped by its users’ imaginations.” This is related to the fact that copiers were very soon liberated from these contexts of use and “quickly adopted and adapted by workers as a tool of subversion—a form of perruque for the information age,” as Kate Eichhorn explains.10 This sort of emancipation and détournement of technologies and infrastructures for one’s own artistic or political agenda can also be observed in the field of POD platforms.

Specific Affordances of POD

Participation and Access

For example, POD plays a key role in participatory contexts because of its low-threshold nature. Formats such as book sprints, which are aimed at the general public and are often used in museum education, art communication, and literature education, are benefitted rather than hindered by being restricted to a few book formats and materials. This is demonstrated by their huge output, such as the Book Machine at the Centre Pompidou Paris in 2013, organized by Onestar Press, which produced over 350 titles in three weeks.

In addition, the POD platforms naturally attract particular interest in the sub-field of restricted production, to use Bourdieu’s term. In contrast to the sub-field of large-scale production, recognition and success here are not measured in terms of sales figures or money. Instead, it is characterized by “an anti-economic economy based on the refusal of commerce and ‘the commercial’ […] and on recognition solely of symbolic, long-term profits.”11 In the field staked out by the Library of Artistic Print on Demand, it was artists’ initiatives like AND Publishing and ABC, as well as publishing collectives such as Troll Thread, Gauss PDF, and TraumaWien that independently, but at around the same time (2010), recognized the potential of POD to “sustain an adventurous and inquiring creative practice without having to conform to the mass market.”12 In this spirit, Troll Thread was founded primarily as a “place to put our poems that no one else wants.” As member Holly Melgard explains:

Why wait to be asked before speaking? What, should I not speak unless spoken to? Why wait for an established person to solicit, welcome, and/or legitimate this work prior to permitting it to occupy public space-time? Self-publishing these books via Troll Thread allowed me to immediately distribute my work to a larger public without predicating what I make on anyone else’s desire or agency besides my own.13

Scale and Scope

For Troll Thread member Joey Yearous-Algozin, POD has yet another unparalleled advantage: “More than simply providing new channels through which to disseminate texts, this shift in platform has allowed for a simultaneous shift in scale. […] [D]igital publishing allows for experiments in volume, with poets literally testing the physical limits of what we call the book.”14 There are several projects that exploit the new digital possibilities for generating texts and produce vast quantities of text. Stephen McLaughlin’s Puniverse (2014), whose subtitle (being the ingenuous crossing of an idiom set and a rhyming dictionary) reveals its underlying principle, comprises fifty-seven volumes filled with hackneyed jokes. That it is possible to order these volumes as physical books that can be held in the hand clearly shows the excessive nature of digital production, with its tendency toward over-production.

Michael Mandiberg’s Print Wikipedia (2015), which squeezed the entire English Wikipedia into the medium of print, also plays with the shift of scale introduced by digitization. The over six million English-language articles on Wikipedia fill more than 7,500 volumes. Just by converting Wikipedia into the familiar book format, the project helps us comprehend the dimensions of the collective writing experiment and the scope of the knowledge that it has assembled. In just a few years, Print Wikipedia will be an invaluable historical document—a snapshot of the state of knowledge at a precise point in time.

Archiving and Urgency

Print Wikipedia also clearly demonstrates that the fast, straightforward POD process is an ideal medium for documenting and archiving ephemeral artifacts and content, especially those from the digital world and Internet culture. When it comes to this kind of fixing of the digital in print, there may well be no medium more appropriate than POD, the epitome of post-digital hybridity. Paul Soulellis, founder of the Library of the Printed Web (2013–2017), was one of the first to identify this artistic web-to-print practice, at the interface between screen and printed page, as a phenomenon of our time. It is intended to suspend the digital condition that is slipping out of our grasp: “The physicalization […] brings focus. […] It slows me down, it helps me to pause and reflect,”15 Rafael Rozendaal reports in his series Abstract Browsing (2016). Soulellis’s own publications are also a good example of this approach, which, in light of political events in the US, he later called “urgent publishing.”

To publish is, fundamentally, a political act.

In moments of crisis, as we’ve experienced so deeply in the last year, we see not only artists, but community organizers, scholars, poets, and activists collectively engaging with different modes of publishing to urgently document and communicate what’s happening, in real time.16

Following this credo, Soullelis’s zine Thank you for your interest in this subject (2017) documents the systematic deletion of countless web pages on whitehouse.gov immediately after Donald Trump’s inauguration on January 20, 2017, at around 17:00. Of course, much of this material, which is documented here in printed form, is now outdated and historical. But this is precisely what makes POD a powerful tool for historiography, as James Bridle notes in reference to his twelve-volume series The Iraq War (2010), which recorded all 12,000 changes made in the edit wars over the Wikipedia article of the same name.17

Teaching and Research

However, as Manon Bruet observes, the POD model “first managed to establish itself in the field of teaching.”18 And indeed, POD has opened the door for books to be used in new ways in research and education, as the apod.li collection demonstrates. Initially, the focus was on basic testing of this new production process, the potential and limitations of which were explored in art schools by emerging designers and typographers. Possibly POD’s greatest impact on teaching has been the extension of the classroom into the book market and the public sphere: POD not only enabled the production, but also the publication of university assignments, seminar papers, and theses, which were otherwise only produced for use in the classroom, and not generally circulated.

The seminars have generated also more extensive artistic (research) projects, and even publishing houses and dissertations, which are now considered as valid contributions to the post-digital publishing scene. Examples are Olivier Bertrand’s Surfaces Utiles publishing house, a “spin off” from his master’s thesis, or Luca Messarra’s Undocumented Press, which emerged from one of Danny Snelson’s seminars. Snelson’s Eclipse Printing Service was, in turn, a subproject of his dissertation Variable Format.19 Some projects, such as Stéphanie Vilayphious’ Blind Carbon Copy series (2009), on experimental ways to circumvent intellectual property restrictions, or Jasper Otto Eisenecker’s Camouflaged Books (2014–16), were not just born in the classroom as master’s theses, but also see themselves explicitly as teaching materials. Eisenecker’s manual How to Camouflage Books in Times of Internet Censorship, also published on the platform he was researching, aims to communicate and enable the deployment of his camouflage publishing strategies for a wider public.

Both Analog and Digital

Jasper Eisenecker’s project also represents an attempt to expand the medium of the book by strategically exploiting the fundamentally hybrid nature of POD publications, where the printed book is always based on a digital master. His Camouflaged Books are intentionally configured as a double pack, comprising both a digital file and a printed copy. They make use of special visual camouflage strategies designed to distort the content of each publication in such a way that the PDF file would outwit the POD platform’s automated checking and control mechanisms, while ensuring the printed books would remain legible and present no difficulties for human readers.

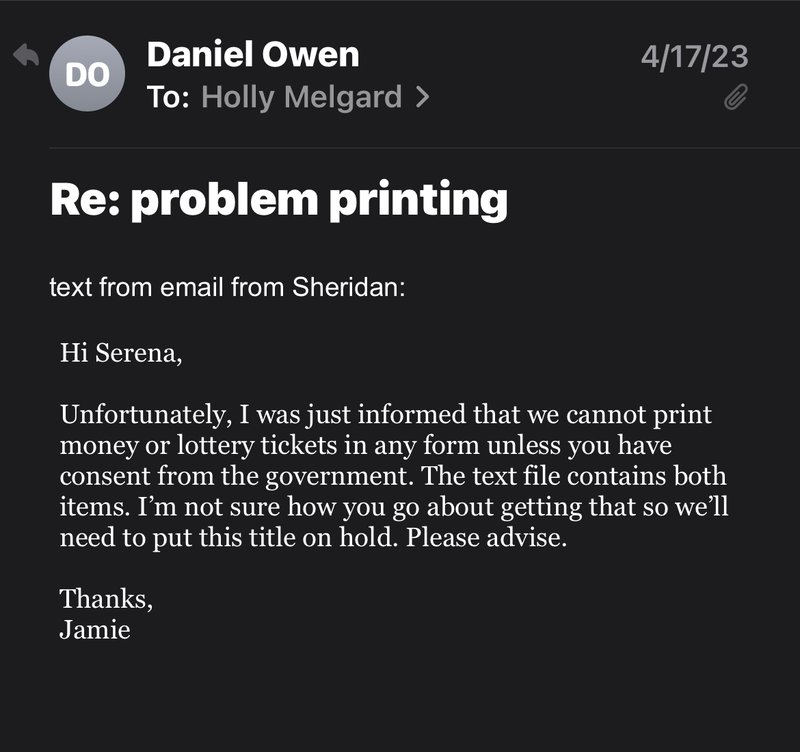

The printed book is not conceived here as a countermodel to the digital, but as a complementary addition. In other words, the two publication formats are not to be understood as an “either–or,” where the reader can choose the preferred format. Instead, these works are conceptualized as a “both-this-and-that.” This dual publication strategy also applies to Holly Melgard’s MONEY (2012), which depicts the front and back of 368 full-size hundred-dollar bills, “inviting the reader to either call cops or cut on the dotted line and use the bills IRL [in real life].”20 In this way, MONEY reveals the anachronism in current law: While the PDF file is unproblematic, executing a print job would amount to the illegal reproduction of banknotes, where it is not clear who could be held legally accountable. This is not a purely abstract question, as the printer’s refusal to print Melgard’s latest book with excerpts from MONEY shows (see fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Message from the printers refusing to print Holly Melgard‘s poetry collection Read Me (New York: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2023). Screenshot.

Publishing through Metadata

One could, however, argue that MONEY does not actually need to be materialized in print to be effective. The idea of the book is already realized in the fact that it could be printed. Sophie Seita describes this aptly as “imagined printedness”: “These are works that cannot or should not be printed but insist on printedness—even if only imagined—all the same.”21 This is a feature of POD in general—after all, every uploaded book must wait to be ordered and printed. But it is especially significant for cases where the high price or sheer scale of the complete work makes it highly unlikely to be ever printed (see Print Wikipedia), or for cases designed to test the limits of platform production (see MONEY).

In such instances of deliberate “imagined printedness,” it might make sense to recognize even the mere uploading of a file to the POD platform, along with the entry of the necessary metadata and the subsequent public display in the store, as a valid act of constituting and publishing a work. Even without having been printed or indeed ever being printed, the mere potential material existence of these books, constituted by their metadata and their embeddedness in the POD ecosystem, creates a fact that allows them to be addressed as full-fledged works, to be attributed to an author’s oeuvre, to be discussed and interpreted, and to be inscribed in the history of art or literature.

Paratext Poetics and Envelope Strategies

Closely linked to this metadata are the innumerable upload and activation processes that need to be gone through to publish a book on a POD platform. They offer another target for intervention. They are controlled through a special interface with mandatory fields for title, author(s), keywords, description, etc. that follow a strict protocol. On Lulu, for example, at least one “contributor” must be entered, and a name alone does not suffice—a role also has to be selected from a drop-down menu with no fewer than thirty choices from co-author, illustrator, editor-in-chief, and thesis advisor to cover designer, annotator, and translator (see fig. 4).

Fig. Lulu’s interface, detail. Screenshot.

This list provides insight into the platforms’ concept of authorship and their attempt to mediate between the highly regulated book trade, with its coarse-grained and often abbreviated entries for names, titles, subject classifications, and other paratexts, and the comparatively unregulated digital world, where, for example, the names of all contributors to a publication can be entered, with no limit on available space. This more accurately reflects the actual collaborative nature of book creation. It also increases reach and findability in digital databases and so the amount of attention books receive—an effect that can be observed, for example, in Mathew Timmons’ Credit (2011), which documents the strained financial situation of the author during the financial crisis. All thirty authors who contributed blurbs to the book are mentioned by name in the online store, demonstrating the significance of symbolic capital in this niche sector of restricted production, whose actors, like Timmons himself, often have limited financial resources and creditworthiness.

Furthermore, these blurbs show the amazing creativity and humor associated with this genre of text, which often extends to other entries in Lulu’s upload forms. This is encouraged by the fact that although most of the fields are mandatory, you can write whatever you want in them. This includes the author’s name, which does not need to be based on a username or a real name. It is thus possible to enter pseudonyms, collective names, or anonymous. In addition, these fields are not exclusive—unlike the login name, an author name can be used multiple times, in different publications, by different users. Moreover, the digital metadata and paratexts can be different from the information given on the cover, fly-title, spine, or title page of the printed book. This expands the artistic options enormously; and several artists thus see it as part of their work and play around with it.

What is particularly appealing here is that these simple requirements for accessing POD platforms also permit entry to the more regulated and change-resistant book trade. For this reason, the POD sector is the arena for a particularly dynamic negotiation and expansion of these paratextual practices. Consequently, these data and paratexts from POD platforms are just as important as those in the printed book and should be recorded in the same way, as integral parts of the work—which is why the apod.li web archive includes a screenshot of each title whenever possible.

Détournement and Hijacking

There have been other attempts to develop subversive or antagonistic ways of using the platforms, confirming the rule that “Institutions cannot prevent what they cannot imagine.”22 The first to be mentioned here is Troll Thread’s publishing model, which subverts the very meaning and purpose of a POD platform. It is based on a simple, extremely minimalist Tumblr page linked to the Lulu online store: “Basically, we use Lulu as a means to host the PDFs, something Tumblr’s platform doesn’t accommodate, without having to pay for our own domain.”23 They thus misuse Lulu as a free storage and virtual gallery space for the presentation of their own publishing program. In his manifesto how to stop worrying abt the state of publishing (2016), Joey Yearous-Algozin openly promotes this strategy, detailing the steps to find the “backdoor way of viewing yr file that lulu is now hosting for you for free.”24

It is precisely this free-rider effect that Olivier Bertrand makes the defining principle of his publishing house Surfaces Utiles. He refers to his publishing practice with the French expression “faire la perruque,” a term used by Michel de Certeau to describe a “practice of economic diversion” whereby employees take advantage of their working time and the working means, resources, or tools of their employer for their own benefit, or to the employer’s disadvantage, whether it is copying on the company’s copy machine, planning the next vacation trip on the office computer, or stealing pencils and envelopes for one’s own correspondence.25 Applied to Bertrand‘s own practice, this means:

It is not necessary to recreate new structures each time, but it is quite possible to rely on those that already exist, even if it means hijacking them. Rather than denying them, we can imagine, for example, taking advantage of the strength of the institutional or industrial structures already in place to transform them according to our needs (and not those of the market). In terms of resources, it is a question of working as much as possible with the materials that are already around us […].26

With this in mind, Bertrand has developed strategies for reusing leftovers and hacking industrial structures. In the case of Blurb, where none of the standard formats met his requirements, he chose the most economical format in terms of its cost-benefit ratio and offered the offcuts, i.e., the unused spaces on each page, to another artist for their own book project. As a form of “perruque” for his own advantage, Bertrand thus implements the same principles for economical and ecological optimizing the print sheet as the POD printers, which enable them to offer their products so cheaply, as one of these printers explains: „One of the most essential reasons for our low prices is the combined printing of different orders during one print run.“27

However, this strategy does not really pay off in the long run. It saves paper and money, but not time. The production of the digital template for merging and superimposing different works is too labor-intensive, especially since it is not transferable to other publications, which all require individual solutions. Nonetheless, Bertrand values the process that allows him an economy of complicity and an upside-down approach: “For me, it was critical to consider design in this way. I think about it from the material to the publishing project, rather than from the publishing project to the material.”28

Outwitting and Hacking

Even more complex was the search for a way to exploit a hidden potential of POD that the platforms did not provide for: combining the production of printed one-offs with generative methods. Despite their boast of offering a micro print run of a single copy, the POD platforms and their APIs do not support the automated upload of print templates with subsequent triggering of a print order that would allow the reader to create and order their own version—perhaps to prevent spam or excessive uploads, or because of the complexity of such a service. This means that in spite of all the automatization and digitization, individual copies still have to be generated and saved singly, with each one manually uploaded and released as a new title. Only after several attempts did Andy Simionato and Karen ann Donnachie succeed in staying true to the name of their project, The Library of Nonhuman Books (2019–), and implementing a fully automated book ordering process, where new book iterations are first generated and uploaded to the platform at the click of a button, and then copies are ordered, paid for, printed, and shipped—all without any human intervention.

Limitations: At the Mercy of the POD-PlatformsNew Intermediaries instead of Self-Publishing

It is important to them that orders are placed through their own publishing website and not Blurb’s or Lulu’s online store, because they wish to remain platform-agnostic and to reserve the option to change platforms if necessary. They have learned the lesson that although POD expands the “horizons of the publishable,”29 it also entails new limitations and dependencies. The emancipation from the traditional publishing industry and its gatekeeping mechanisms is only one side of the coin. After all, the system of mediation does not simply disappear. Instead, new intermediaries emerge in the form of POD platforms and a self-publishing industry that are nothing more than “refashioned gatekeeping.” Strictly speaking, therefore, it is misleading to speak of “disintermediation” or “self”-publishing: “the word self masks the extensively collaborative process of self-publishing” and its inevitable interconnectedness with providers and infrastructures under platform capitalism.30

At the Risk of Deplatforming

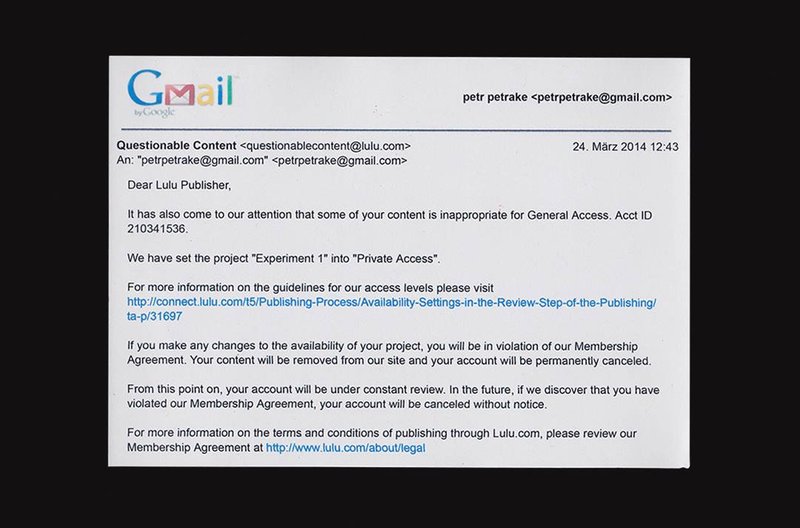

It is also well known by now that platforms are not neutral service providers, but are themselves political actors that create realities. They use their terms and conditions and their absolute authority within their own domain to dictate what users can do and the rules they must follow. These terms and conditions have been cited in several cases as the basis for blocking or deleting books or accounts (see fig. 5).31

Fig. 5 : Notification from Lulu’s Questionable Content Team, March 24, 2014.

What makes the situation even more complicated and opaque is the fact that the platform’s partner printers also have the right to refuse to execute certain orders.32 The worst-case scenario is when a user’s entire account is blocked because of a single book as happened to Danny Snelson. With this deplatforming, all the books that students have created in his seminars over ten years have been lost. Artists have rarely succeeded in convincing the Questionable Content Team that the allegation was baseless and reinstating their account, as in the case documented here (fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Email correspondence between Lulu’s Questionable Content Team and an artist represented in apod.li from August 2021 (personal details redacted).

Volatility and Vulnerability

Users are also completely at the mercy of sometimes drastic changes to the platform structures and features. In 2009, paula roush experienced how users can lose control of their carefully maintained profiles when Lulu suddenly removed the Community Blogs feature, which was originally intended to support social networking by users and the formation of a Lulu community (see fig. 7). All the material posted there was ruthlessly deleted with only a few days’ notice (see fig. 8). roush, a pioneer in the use of POD for teaching, lost two years of coursework produced with her students using Lulu blogs.

Fig.7: Lulu’s former community features. Screenshot.

Fig. 8: Lulu’s notification about the removal of community blogs, January 27, 2009 [personal details redacted].

Troll Thread also faced a rude awakening when they were taken unawares by an extensive relaunch of the Lulu online store in 2020 that defeated their sophisticated parasitic strategy at one stroke. Not only were all publications given new links, with numerous publications and accounts deactivated, but the preview function was also deleted—and with it the basis of Troll Thread’s hack, once again revealing the POD platforms as an embattled territory, where artistic imagination and use push up against techno-economic optimization and regulation.

Sustainability and Resilience

In the end, POD has proved to be an astonishingly precarious genre, despite unlimited print runs and enduring availability being touted as selling points of the POD publishing model. A considerable number of titles (not limited to the apod.li collection) are now no longer accessible, whether due to acts of censorship, alleged copyright infringement, economic considerations, changes in formats, materials, or design features, price increases, or even the closure of POD platforms. With this in mind, one has to agree with Silvio Lorusso, who identifies volatility as a pressing issue for expanded publishing and concludes: “So the point is, how to make a lasting publication? […] the question of sustainability […] is the part that requires more experimentation, more than coming up with a new file format.”33 But perhaps its temporary nature is the very essence of experimental publishing? Institutionalizing and perpetuating the experiment is, after all, ruled out by definition. From the artist’s point of view, then, what is needed above all is a certain tenacity and versatility, as practiced by Joey Yearous-Algozin: “to put it bluntly: these things work for now and once they stop working, we’ll find something else.”34

-

The Library of Artistic Print on Demand (hereafter apod.li) contains a selection of 244 outstanding POD publications, representing a vibrant experimental field of post-digital book culture that emerged with the establishment of POD platforms around 2005. The collection is held by the Bavarian State Library Munich and documented in a web archive: https://apod.li. A comprehensive catalogue, edited by Annette Gilbert and Andreas Bülhoff, will be published by Spector Books. This text is based on the introduction there. ↩

-

Emilie Mathieu and Juliette Patissier, Enjeux & développements de l’impression à la demande (Paris: Editions du Cercle de la Librairie, 2016), 21 and 22. ↩

-

Clay Shirky, “How We Will Read,” interview by Sonia Saraiya, Findings.com, April 5, 2012, https://web.archive.org/web/20120504030525/http://blog.findings.com/post/20527246081/how-we-will-read-clay-shirky [emphasis in the original]. ↩

-

Timothy Laquintano, Mass Authorship and the Rise of Self-Publishing (Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 2016), 3.—In 2008, break-even was reached when the number of ‚non-traditional PoD books produced in the US exceeded that of ‚traditional‘ publishers for the first time. Cf. Bowker, Self-Publishing in the United States 2008–2013, 2014. ↩

-

Both citations Laquintano, Mass Authorship, 43. ↩

-

Silvio Lorusso, “Print-on-Demand—The Radical Potential of Networked Standardisation,” in Code—X. Paper, Ink, Pixel and Screen, ed. Danny Aldred and Emmanuelle Waeckerle (Farnham: bookroom, 2015), 03:47–03:58, 03:48. ↩

-

Eileen Gittins cited in Bruce Rogers, “Eileen Gittins Builds Blurb to Make Book Publishing Easy and Affordable,” Forbes, January 28, 2015, https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucerogers/2015/01/28/eileen-gittins-builds-blurb-to-make-book-publishing-easy-and-affordable/. ↩

-

Lorusso, “Print-on-Demand,” 03:52. ↩

-

However, this network is not as global as the providers like to claim. There are hardly any official figures, but RPI Print—Blurb’s founding partner—at least locates the partner printers of its “global network” on a world map, the clustered distribution of which clearly indicates the concentration on a few key regions in the US and Europe. Cf. RPI Print, “Our Global Network,” RPI Print, https://www.rpiprint.com/products-services/services-printernet-networks/. ↩

-

Both citations Kate Eichhorn, Adjusted Margin: Xerography, Art, and Activism in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge, Mass., and London: MIT Press, 2016), 21 and 34.—Lisa Gitelman makes a similar point in Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 84. ↩

-

Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993), 54 [original emphasis deleted]. ↩

-

The Piracy Project, “The Impermanent Book,” in Best of Rhizome 2012, ed. Joanne McNeil (Brescia: LINK Editions, 2013), 21–27, 27. ↩

-

Both citations Holly Melgard, Essays for a Canceled Anthology: HOLLY MELGARD READS HOLLY MELGARD (self-pub.: Troll Thread / Lulu, 2017), 20 and 7. ↩

-

Joey Yearous-Algozin, “Keep your Friends Close /// We Upload Trash,” Convolution 4 (2016): 75–79, 78. ↩

-

Rafaël Rozendaal, “Notes on Abstract Browsing,” https://www.newrafael.com/notes-on-abstract-browsing/. ↩

-

Paul Soulellis, “Urgent Publishing after the Artist’s Book: Making Public in Movements towards Liberation,” APRIA Journal 3 (October 2021): 31–34, 32, https://apria.artez.nl/urgent-publishing-after-the-artists-book/. ↩

-

Cf. James Bridle, “On Wikipedia, Cultural Patrimony, and Historiography,” booktwo.org, September 6, 2010, http://booktwo.org/notebook/wikipedia-historiography/. ↩

-

Manon Bruet, “Production Process: Print on Demand,” Revue Faire No. 26 (2020): n.p. ↩

-

Daniel Scott Snelson, “Variable Format: Media Poetics and the Little Database” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2015), https://monoskop.org/images/8/8c/Snelson_Daniel_Variable_Format_Media_Poetics_and_the_Little_Database_2015.pdf. ↩

-

Melgard, Essays for a Canceled Anthology, 11. ↩

-

Sophie Seita, “Thinking the Unprintable in Contemporary Post-Digital Publishing,” Chicago Review 60, no. 4 (Fall 2017): 175–194, 175. ↩

-

Craig Dworkin, Simon Morris, and Nick Thurston, Do or DIY (York: information as material, 2012), front matter. ↩

-

Joseph Yearous-Algozin in Tan Lin, “Troll Thread Interview,” Poetry Foundation, March 4, 2014, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2014/05/troll-thread-interview. ↩

-

Joey Yearous-Algozin, how to stop worrying abt the state of publishing, (self-pub.: Troll Thread / Lulu, 2016), n.p. ↩

-

In more detail, Certeau says: “Into the institution to be served are thus insinuated styles of social exchange, technical invention, and moral resistance, that is, an economy of the ‘gift’ (generosities for which one expects a return), an esthetics of ‘tricks’ (artists’ operations) and an ethics of tenacity (countless ways of refusing to accord the established order the status of a law, a meaning, or a fatality).” Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1984), 26 and 27 [emphasis in the original]. ↩

-

Olivier Bertrand, Froncer les sourcils (self-pub.: Blurb, 2017), 100 [our translation]. ↩

-

“FAQ: Can I increase the amount ordered afterwards?,” Print24, https://print24.com/uk/faq. ↩

-

Olivier Bertrand, interview by the author and Andreas Bülhoff, March 5, 2021. ↩

-

Rachel Malik, “Horizons of the Publishable: Publishing in/as Literary Studies,” ELH 75, no. 3 (Fall 2008): 707–735. ↩

-

Both citations Laquintano, Mass Authorship, 9 and 23 [emphasis in the original]. ↩

-

Cf. “Blurb may terminate your membership at any time and for any reason […].” Blurb, “Terms & Conditions,” §2, https://www.blurb.com/terms. ↩

-

“[…] our print partners may refuse to print content that they consider pornographic or offensive.” Blurb Help Center, “Will Blurb print adult content such as nudity?,” last modified in 2019, https://support.blurb.com/hc/en-us/articles/216494063-Will-Blurb-print-adult-content-such-as-nudity. ↩

-

Silvio Lorusso in Conversation on Expanded Publishing, July 2, 2024, https://etherport.org/publications/inc/expub_Expert_Session/chapters/silvio-lorusso.html. ↩

-

Yearous-Algozin, “Keep Your Friends Close,” 78. ↩