chapter

11 Dušan Barok

4 July 2024, 12:00 PM

Introductions

07:40 To briefly introduce my background: I studied Information Technologies in Bratislava, Slovakia, where I grew up. Parallel to my studies, I was involved in the local non-profit culture scene, mostly between art and technology. In the late 90s, I started a small cultural magazine, but we soon lost the funding needed for print runs. A friend introduced me to HTML and I realised that it could be a better solution than paper because, at that time, people already had access to the web. That’s how I discovered digital objectsweb publishing. We redesigned our first website, which was called referencesKoridor, every few months, exploring different ways it could be organised and designed. At the time, we called it a “portal”. The idea emerged to set up a website that would document our work, which grew into Monoskop, two or three years after Wikipedia arrived. Suddenly, there was toolssoftware that allowed people to put things online without understanding programming. This was before content management systems like WordPress existed. The MediaWiki installation we set up is still there and operating. It has grown into a huge, lively, multilingual wiki for arts and studies.

In the early 2010s, I did my Master’s in Rotterdam at the Piet Zwart Institute, a program which is now called XPUB but at the time was called Networked Media. toolsIt was an eye-opener, especially in terms of using free software and an interventionist way of working with technology, and tools that built things. It involved writing HTML files in the text editor, using Terminal and doing prototyping, which greatly influenced my work ahead.

Why: Politics of Publishing

17:08 We tend to see archives as frozen in time, a collection of things that are stored in a dark room to be looked at or, at most, touched with gloves. How do you see new ways of publishing as fostering archives as living entities? Can we publish living archives?

18:24 In a way, printed objectsprint is archiving of the digital, while digital objectsthe digital is constantly changing. Oftentimes it disappears, or only remains in the web archive. However, even with live websites, things get reformatted, designs, content and embedded media change. So, in digital publishing, unlike in print, you never really have a final version. This is also how print publishing operates, working with the PDF as an intermediary between content production and the print.

One can see how the environment and the ways of navigating it changed over the years — I would say that in the 2010s, we lived through the era of social mediasocial media, which was sucking increasing amounts of attention. We eventually stopped clicking on those links and ended up scrolling. The scroll silos have locked us in, and the experience of the web has essentially shrunk to a handful of websites, with everything else remaining invisible or being subsumed into the platforms. Today, it’s even worse with AI. We were expected to use our critical faculties to filter out relevant social media posts and search results, but AI chatbots give us only one answer, which, by the way, is likely wrong and unsourced.

The question for digital publishing and web publishing is how to operate in this context, which is very different from what the web was 10 years ago. governance and ownershipThe experimental artistic approach would be, for example, to develop our own chatbots, train our own AI tools and figure out how to work with AI in a sustainable way that doesn’t burn the planet and credits the sources. One would not build a general knowledge AI, but a focused, topical AI. If artists build these tools, they will treat what they do as a data set for training bots. In classical pre-publishing, this would be the type of thinking that goes into creating anthologies, or where we collect different sources and bring them together under a thematic umbrella. Maybe it’s interesting to think about publishing today as creating and producing content-based datasets that can train AI to serve different purposes and different audiences while being aware of what’s happening with this Silicon Valley approach, and how to do publishing sustainably.

How: Infrastructures of Publishing

25:43 In the Netherlands, some museums already use AI to make archives more accessible, reducing the threshold of archival knowledge and opening it up to people who do not yet know how to search from a specific archival studies perspective. One can just ask the archive for data the way you’d ask a chatbot. It’s interesting to think of these technologies serving a more cultural purpose. Building on this notion of cultural and public value, I wonder, how do look at the infrastructures for linked open data? How can we create stronger networks between repositories?

26:50 I was never very good at linked open data. digital objectsNow, when people look at shadow libraries, they say that really good work has been done to make these things available. On the other hand, we end up sustainability of workflowsfeeding ChatGPT and similar companies that get a lot of value out of this free labour. This is an interesting argument to think about not just in terms of shadow libraries, but in terms of everything that is published online. What can we do about it? Monoskop consists of a lot of pages and files but metadata is not as standardised as Wikidata. It has a classic digital library, and there is always some kind of metadata, but it’s meant for a full-text search. I never thought it would get this big. At the size it is now, one can find anything with a full-text search, but the Monoskop dataset is useless for training bots because there’s no structured data. It’s a collage of different texts, images and PDFs. It may have been a lazy approach but at the moment it looks counterproductive to what’s happening on the web, how content is being sucked up by AI. At the same time, I think we should build datasets. There is a way to think about it without the grand-scale vision that it has to be an all-knowing machine.

I will give you an example of a small projec, which was part of Monoskop: an anthology of articles about shadow libraries. It is based on the Monoskop wiki section on shadow libraries, which has a lot of articles. I took those articles, converted them to Markdown, and put them in a directory. Then I ran the TF-IDF algorithm, which identifies words or phrases that are specific to a text. For example, if you click on Infrapolitics, it will give you referncesNanna Thylstrup’s text. For text or corpus analysis, it’s one of the most basic algorithms, but it’s very powerful. You can twist or tweak the algorithm in whatever way you find interesting. When I made this project, I used a corpus analysis tool as its main interface. But if I would do it again today, it would probably end up looking like a chatbot.

Who: Community of Publishing

35:44 New, non-linear structures, like linking and tagging stimulate new ways of reading and cultivate new readership communities. But they also create new dependencies. For instance, wikis are very labor intensive, counting on the community of readers to contribute and maintain it. How can you maintain Monoskop long-term? What is your community?

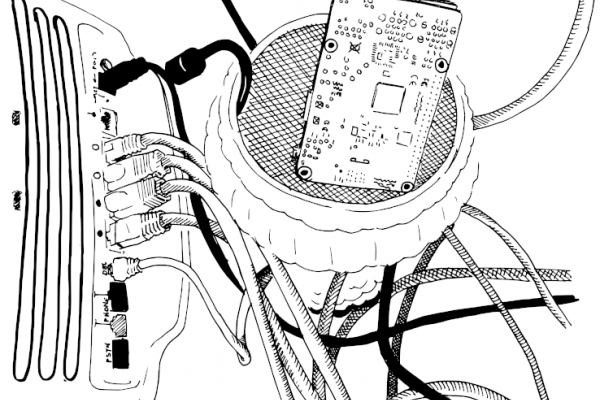

36:43 governance and ownershipWe have been able to maintain Monoskop for so long because we run our own infrastructure. Since 2008, we have our own computer server. We don’t even have a rack. It’s not a virtual machine, it’s a real piece of metal, sitting in a small server house in Prague. It runs Monoskop and almost 100 other domains, platforms and websites, and we are two admins. I’m not very good with server administration, but I’ve been learning it for many years, so by now I know how to set up an email account or a domain. Operating botht the hardware and the software is important, because we keep total control over the environment that makes these websites available to the public. If Monoskop were on a commercial provider, they would cut us off sooner or later.

The legal entity behind the server is an NGO that ran a festival for many years. business modelsIt used to run partly on grants when we did events. Now our main source of income is donations, and we have one or two websites for larger cultural initiatives that we charge for. We’ve been able to run it this way for 17 years.

In terms of traffic and security, we’ve had some attacks, and it requires work on our part. It’s not easy to run a server but it’s possible: there are so many community servers communityout there and some of them are run by artists. Many communities have their own infrastructure, but they are often overlooked, invisible and considered “too geeky”. These marginal practices are crucial for working and experimenting with the web over the long term.

Discussion

42:30 We only see infrastructure when it’s broken or when there’s a problem, because infrastructure is supposed to be seamless and practically invisible. We notice the tap when the water stops running. But that doesn’t mean the tap is any less important when it works well. This might be a good time to pass on the mic to the rest of the table. Does anyone have any questions?

42:57 I would like to know more about the editorial process behind Monoskop. The wiki is open to everyone, but I’m curious to know how you collaborate, and how the editorial process and workflow is structured.

43:33 We never had a clear definition of what we were doing. It’s not clear if it’s a publishing project, documentation, or an artwork. No one knows what Monoskop is. If anything, it was socially determined from the beginning. It started in a physical space, a media lab called Burundi in Bratislava in 2004, and the first users were members of the place. If any of these people created an account on this Wiki, they were likely to contribute something relevant, whether that was changing information in an article, adding contextual information, uploading a missing file, or creating new articles.

I look at the recent changes almost every day to see what’s happening, but very rarely do I have to delete anything. Sometimes I email authors but usually they contribute to Monoskop mostly through social links. I almost always work with a few people who know the subject, like sound art or federated networks, much better than I do. For the sound art section, I’ve worked with two others from the start. For the section on federated networks, I talked to people involved in federated networking from the start and asked what should be there. I have worked with Ilan Manouach on the conceptual comics section, being mostly a technical help. He could do nearly everything by himself.

49:11 When I started an archive of comics, I discovered Anna’s Archive, a huge repository containing 5% of the books that have been printed by humanity, LibGen, and Sci-Hub, and Anna’s Archive. As a researcher, it’s quicker for me to go get papers on Sci-Hub and books on LibGen than go through my university’s library access, which is antiquated. I need to ask for permission and then the book comes two weeks later. Piracy works better than any of the alternatives.

Is it enought today, in 2024, to put media online, or should we try to find new ways to deal with distribution and dissemination of knowledge? What are the next steps? How do you distill knowledge today in ways that are both democratic and with the same ethical principles that Monoskop started with?

49:21 It’s true that Monoskop Log in particular started with our discovery of Russian shadow libraries in the late 2000s, where we found media theory books that we heard about, but never had access to. It was exciting to make things public. By 2008 or 2009, Gigapedia had hundreds of thousands of books, and it made sense to copy some of those files into a more thematic repository. Most content on Monoskop was copied, an assembled context within the web that has always been huge. This has not changed. Acts of filtering, selecting, highlighting and re-contextualising make the difference, also if the repository is treated as a data set for training neural nets.

54:08 I’m curious to know about your relationship with publishers. What’s your take on hosting books or PDFs of other publishers? Do you have a collaboration, silent communication with them or legal problems?

54:49 That’s a big question! For example, the multimedia institute — MaMa — in Zagreb been around for many years. They do amazing things with the public. Hardt and Negri published a theory book with them in Croatian in 2003. They find books that are in English and, a few months later, publish them in translation. In the 2010s, I visited MaMa and found out they like Monoskop. They decided that they would share all their books with us. Each time there was something new, they would send me a PDF and their Monoskop page became a large MaMa library. digital objectsThey are also open about it: one can always buy the book or download it from Monoskop. They don’t sell PDFs, only the print copies. business modelsIt turned out that free digital distribution helps print sales, because the more people read the books, the more they're discussed. digital objectsIf you’re a researcher and you want to reference or find something, you need a PDF. printed objectsBut if you want to read the book cover to cover, print is better. That’s how it will always be.

Most authors of books that appear on Monoskop are aligned with the copyleft, and they are generally happy that more people can access their work. Sometimes, publishers don’t like a certain book to be there, in which case we delete the files. Of course, these books are in other libraries — maybe they don’t know about it or maybe they do. It’s also not like everyone searches for a book online before they buy it. People look for books online because they’re mostly researchers and they need to find something quickly. I don’t think selling ePubs helps that much.

1:00:13 The Internet Archive was forced to remove half a million books published a big corporate publisher from their archive because of a lawsuit in the US. In Italy, some of the shadow libraries are banned. One cannot access Anna’s Archive, Library Genesis and Sci-Hub, unless with a VPN. I live in the Netherlands and the same is happening here. These are tragedies in our field of work. Have you ever encountered these kinds of issues and, if you did, how did you deal with them?

1:02:34 Publishing is a very broad term, even when it comes to books. Monoskop is not a site where you would find blockbuster books that were made as consumer products, because they are not relevant to our project. You can probably find those on the Internet Archive, which may be why it triggered commercial publishers to take action. Then there’s academic publishing, probably publicly funded, and other kinds of publishing, sustained by publishers not connected to universities or academia. Sci-Hub mostly consists of publicly funded content coming from researchers at universities. governance and ownershipI think it’s ethically wrong what’s happened to the whole academic publishing field, that it’s ended up with five big publishers who own all the journals. University libraries have to cut off access to a lot of these journals, or whole packages of journals, because they simply can’t afford it. What Sci-Hub does is a necessity today for researchers worldwide to survive, otherwise, the life of an academic is very limited, even with access to university libraries. But with other publishers who are not blockbusters and who are not academic, it’s mostly about the revenue. It’s case by case. If the book is good, the free digital distribution does help sales. There are examples like Alessandro Ludovico’s books that are openly access. I think his first book, “Post-Digital Print”, went through three or four printings, and the book was launched on the Monoskop Log. On the day of the launch, they gave me a USB stick, I put it on Monoskop Log and that was the first day the book was published. He did the same with new books with MIT Press, it’s open access, and I think it does help the sales. So if the book is not good and it appears online, people might see that it’s just not good and they will not buy it, but it’s really hard to talk about in general. I would say that I totally support all publishers and I don’t do it to hurt them, I do it to support them and to give visibility and access to their work because maybe they can’t do it, even if they would want to, which was also a case I heard many times.

1:08:04 It looks like if you’re on Monoskop or a shadow library, it means that the book deserves attention, so it can be a way to give value to a publication.

1:08:18 People sometimes go “bingo!” when they find their books showing up on the Monoskop Log.

1:08:53 Dušan, you brought up open-access publishing. As an academic, I see there’s a new ideology evolving around it. We tried to publish a book with De Gruyter, which is an important academic publisher, and they asked for 10,000 euros for open-access. It’s a new business model. Why do I have to fundraise as a researcher?

1:09:25 They ask you for this amount, because they can afford it. If you work with a normal, small, or medium-size publisher, they would say “We can talk about open access”, but they would never ask you for 10,000 euros.

1:09:49 Exactly. I would like to contrast open access and piracy again. What is the new term for piracy? I thought it was an interesting way to remain in the system, but I’m more interested in things outside of the system with unsolicited networks of distribution. It doesn’t have to be a professional quest or something you have to pay, ask your university to find money to open access and I’m not accessing anything. I use proprietary things and then I put it on piracy. I send links to everyone. I provide access to SCDB, I just give it to every researcher who asks for it. I’m wondering if you see this tension also in Monoskop. It can be co-opted by saying it’s very important. For me, my ethics are: no, you should refuse interpretation. To say that you are involved in piracy, you are not involved with open access. Whatever they put away, you’ll take whatever you find interesting and put it on your website without any open access.

1:11:18 There is a language that has developed around open access, with colours: gold, yellow, green, etc. My experience with publishing in the Netherlands: I was at the university there and then we managed to publish two articles in journals which are not open-access. But the Netherlands already had a program at the time — this was five, six years ago — where it was relatively easy to tell the journal that I’m from a Dutch University and they connect to it and charge them, so I didn’t need to do much. Maybe they only had a limited amount of papers they could support every year, a few thousand. I don’t know how is it now. I’m not an expert with open access, it’s probably better if you talk to someone else, Janneke Adema or Gary Hall, who spent a lot of years researching this. Open access is a really broad field within which you have kind of different modalities and different economies and I don’t know how they work exactly.

What: Future of Publishing

1:13:45 Where do you see publishing going, and where you would like to see it go?

1:14:23 For many reasons, websites have an average life-span of three years. Sooner or later, we will have to look at archiving platforms digitally. Recently, I worked on a project called Art Doc Web. The idea was to create an artist website archive of 20 artist based in Berlin. With a collaborator, I was responsible for development. We found that the tools we need already exist, open-source, and are relatively easy to use. We only needed permissions from the artists. They didn’t need to send us anything. One tool would make an archive of somebody’s Instagram account, for example. Each of these web archives is just one file, and when I click on it, it is loaded, opened and rendered in a browser in a way that it feels like it’s a live website, but it’s not live. You can search for images and text within this archive website, so it is fully functional. I would emphasise the importance of thinking about these platforms, that we want them to be live, to have things added. At the same time, we also want to keep them. These are parallel concerns.

1:17:47 Thank you so much for sharing your experiences, your projects and your thoughts.

1:18:45 Thanks for having me.